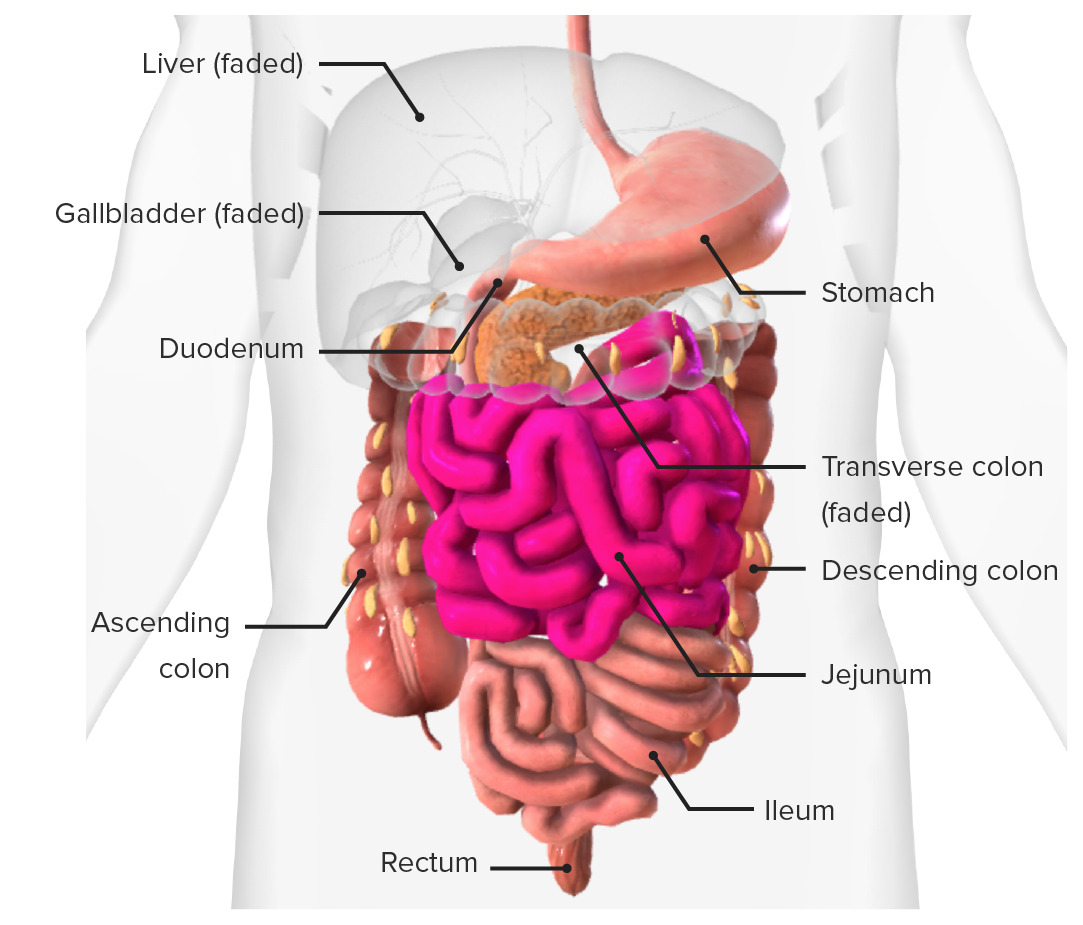

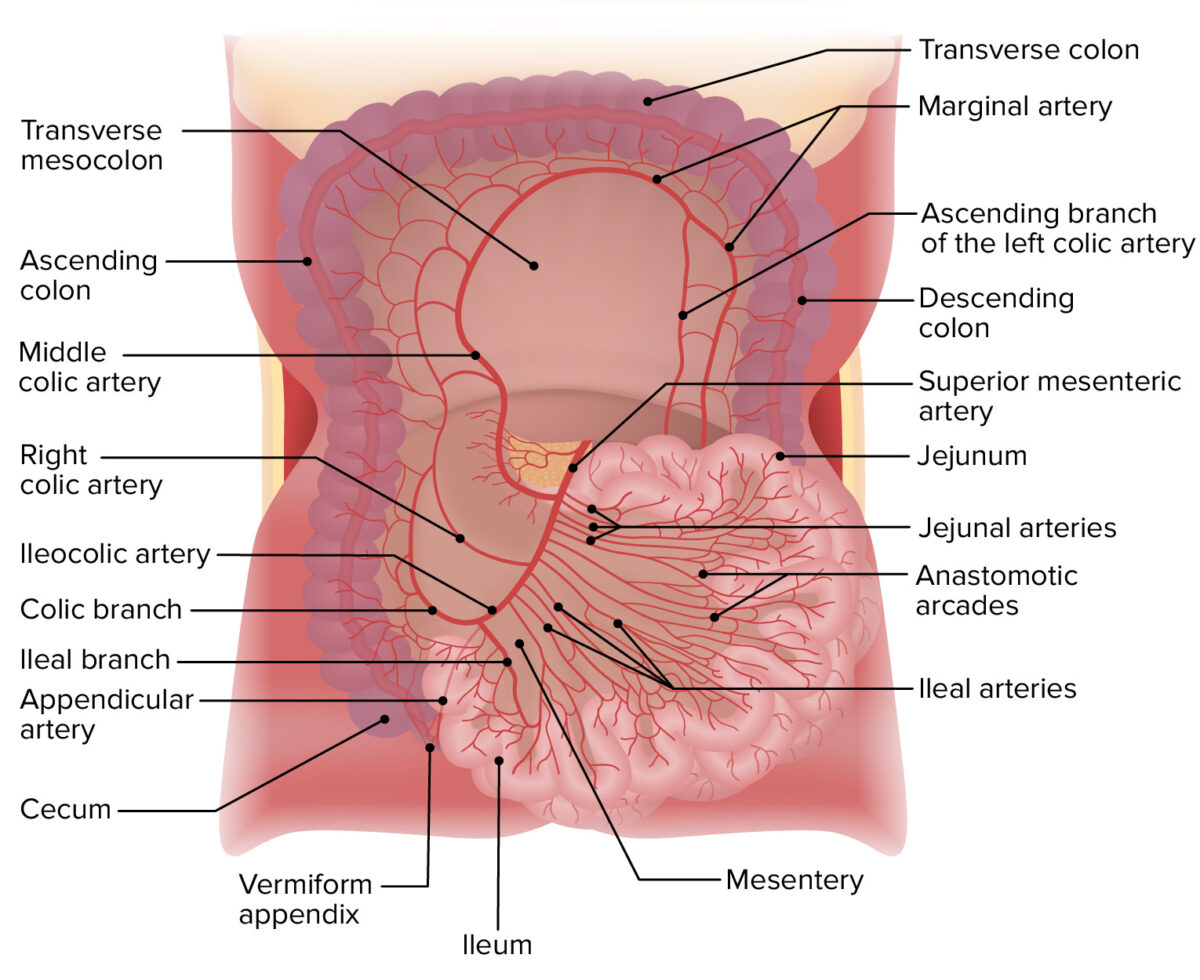

The small intestine is the longest part of the GI tract, extending from the pyloric orifice of the stomach Stomach The stomach is a muscular sac in the upper left portion of the abdomen that plays a critical role in digestion. The stomach develops from the foregut and connects the esophagus with the duodenum. Structurally, the stomach is C-shaped and forms a greater and lesser curvature and is divided grossly into regions: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. Stomach: Anatomy to the ileocecal junction. The small intestine is the major organ responsible for chemical digestion Digestion Digestion refers to the process of the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food into smaller particles, which can then be absorbed and utilized by the body. Digestion and Absorption and absorption Absorption Absorption involves the uptake of nutrient molecules and their transfer from the lumen of the GI tract across the enterocytes and into the interstitial space, where they can be taken up in the venous or lymphatic circulation. Digestion and Absorption of nutrients. The small intestine is divided into 3 segments: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. Like the entire GI tract, the walls of the small intestine have several layers: an inner absorptive mucosal layer (which is made up of an epithelium Epithelium The epithelium is a complex of specialized cellular organizations arranged into sheets and lining cavities and covering the surfaces of the body. The cells exhibit polarity, having an apical and a basal pole. Structures important for the epithelial integrity and function involve the basement membrane, the semipermeable sheet on which the cells rest, and interdigitations, as well as cellular junctions. Surface Epithelium: Histology, lamina propria Lamina propria Whipple’s Disease, and muscularis mucosa) and submucosal, muscular, and serosal layers. The arterial supply to the small intestine is via branches of the superior mesenteric artery, and veins Veins Veins are tubular collections of cells, which transport deoxygenated blood and waste from the capillary beds back to the heart. Veins are classified into 3 types: small veins/venules, medium veins, and large veins. Each type contains 3 primary layers: tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia. Veins: Histology drain into the hepatic portal Hepatic portal Liver: Anatomy system. The small intestine is innervated by the ANS ANS The ans is a component of the peripheral nervous system that uses both afferent (sensory) and efferent (effector) neurons, which control the functioning of the internal organs and involuntary processes via connections with the CNS. The ans consists of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Autonomic Nervous System: Anatomy.

Last updated: Dec 15, 2025

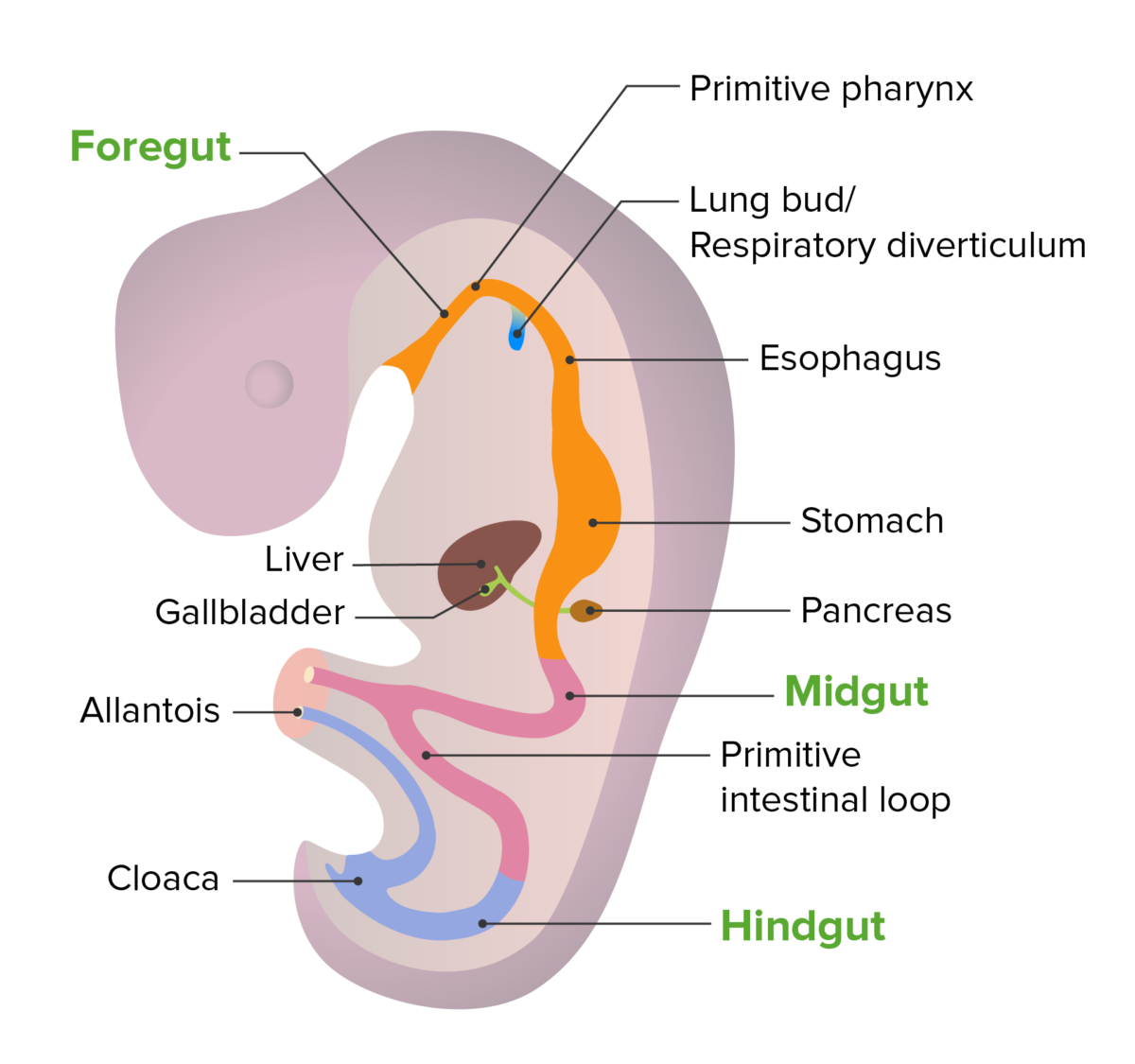

Embryonic development of the gut tube

Image by Lecturio. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0The small intestine is a long tubular structure in the abdomen that is responsible for approximately 90% of nutrient absorption Absorption Absorption involves the uptake of nutrient molecules and their transfer from the lumen of the GI tract across the enterocytes and into the interstitial space, where they can be taken up in the venous or lymphatic circulation. Digestion and Absorption.

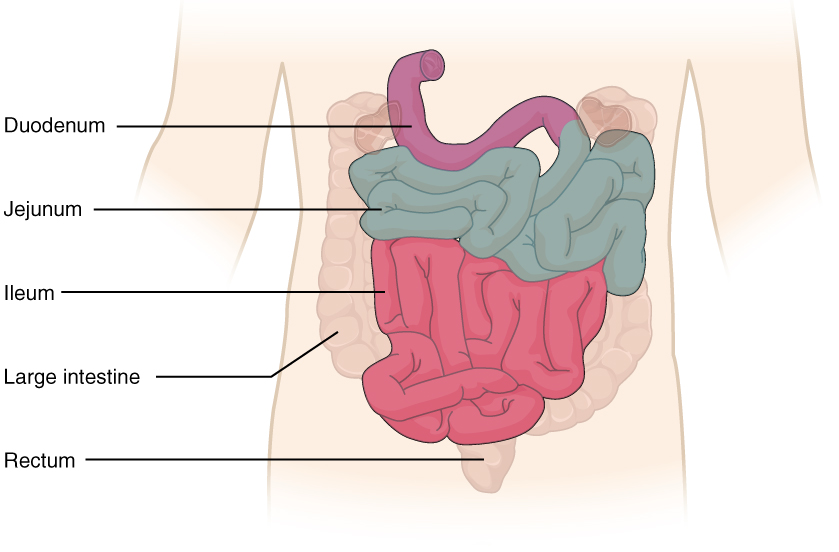

Small intestine and its parts

Image: “2417 Small IntestineN” by OpenStax College. License: CC BY 4.0General characteristics and anatomic relations:

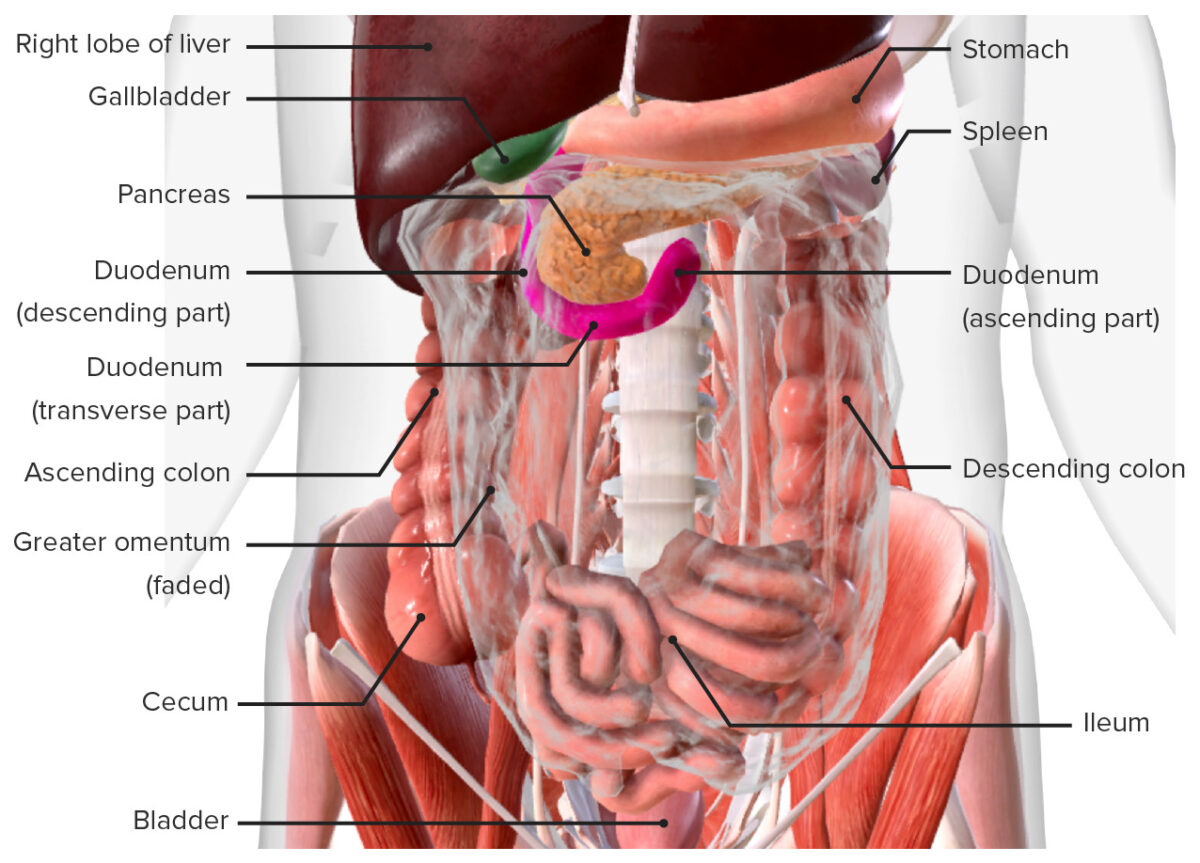

Parts of the duodenum:

The duodenum consists of 4 parts (from proximal to distal):

Duodenum in situ:

Note that the transverse colon, which normally lies in front of the duodenum and pancreas, has been removed from this image.

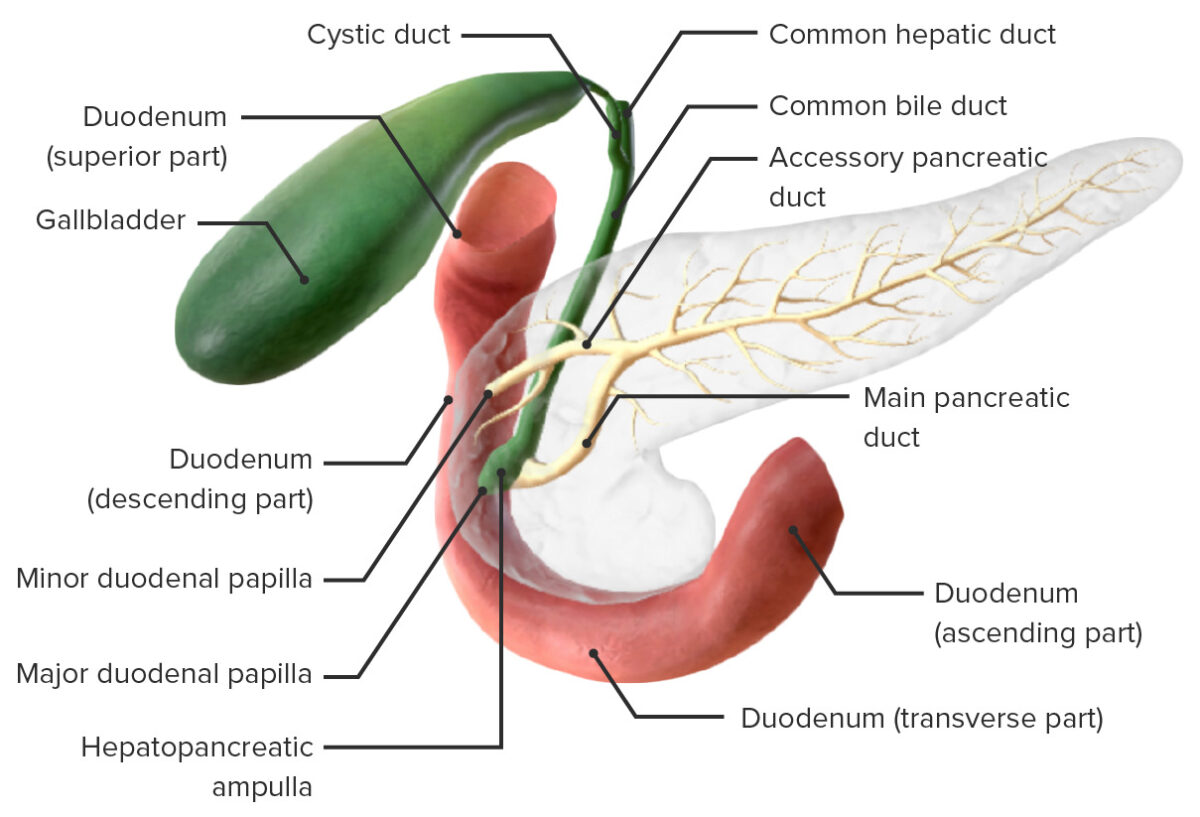

Anatomy of the pancreatic ducts

Image by BioDigital, edited by LecturioThe jejunum and ileum make up a majority of the small intestine as a long winding tube filling a large portion of the abdominal cavity. Both are completely intraperitoneal Intraperitoneal Peritoneum: Anatomy (within the peritoneal cavity Peritoneal Cavity The space enclosed by the peritoneum. It is divided into two portions, the greater sac and the lesser sac or omental bursa, which lies behind the stomach. The two sacs are connected by the foramen of winslow, or epiploic foramen. Peritoneum: Anatomy).

Small intestine:

Location of the small intestine in situ

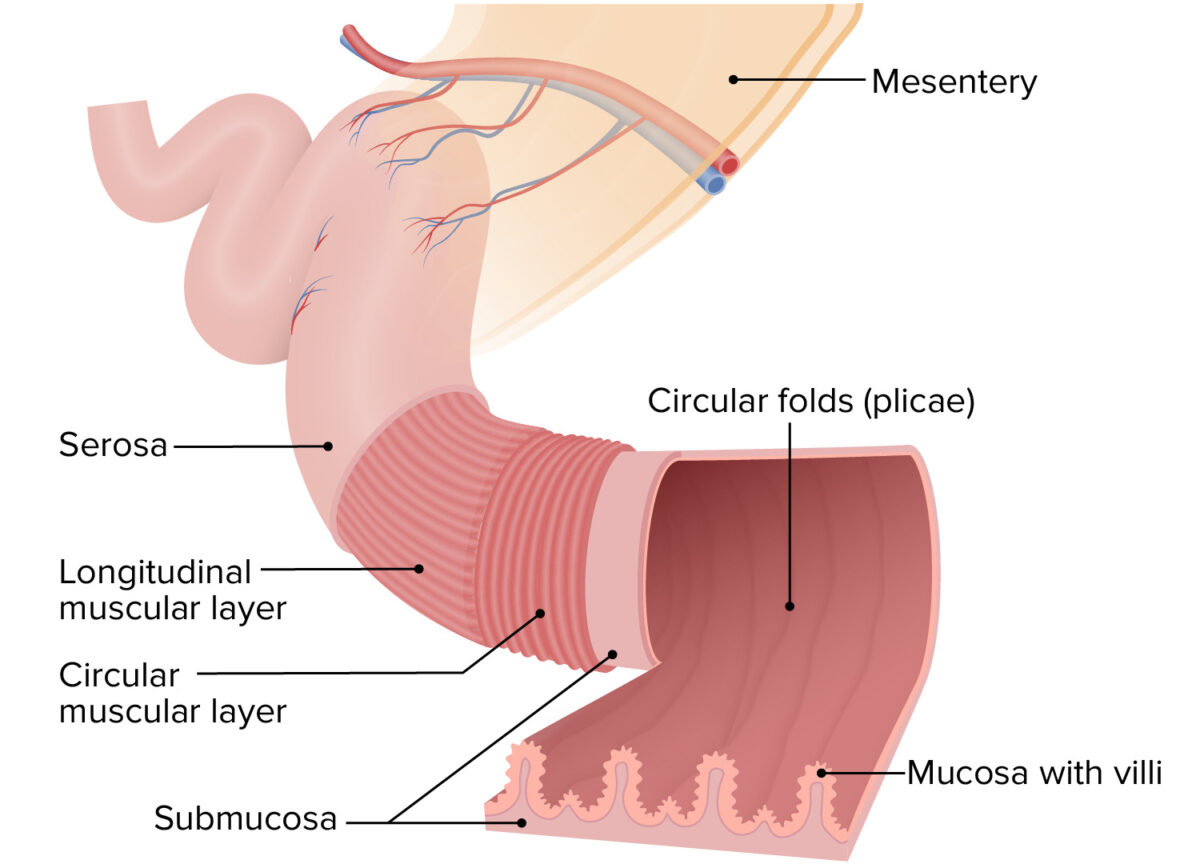

Similar to other segments of the GI tract, the layers of the small intestinal wall (from the inner lumen outward) are mucosa → submucosa → muscular layer → serosa. The walls have several different types of folds.

Circular folds (known as plicae):

Intestinal villi:

Layers and folds in the intestinal walls

Image by Lecturio.Mucosa:

Submucosa:

Muscular layer:

The muscular layer is made up of 2 layers of smooth muscle that mix and move chyme along the tract.

Serosa:

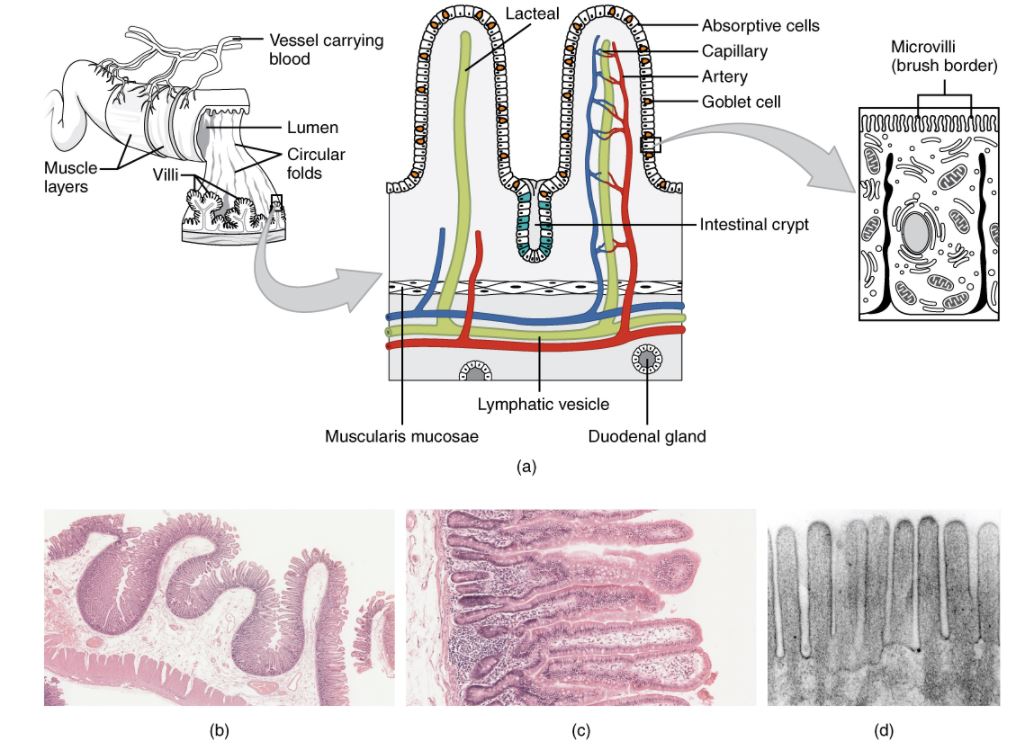

Histology of the small intestine:

(a): The absorptive surface of the small intestine is vastly enlarged by the presence of circular folds, villi, and microvilli.

(b): Micrograph of the circular folds: Note that the folds contain both the mucosa and the submucosa.

(c): Micrograph of the villi: Note that the villi contain only the epithelial and lamina propria layers of the mucosa; the muscularis mucosa is visible as a “pink line” along the left edge of the slide.

(d): Electron micrograph of the microvilli: from left to right—light microscope, ×56; light microscope, ×508; electron microscope, ×196,000

Characteristic differences between the jejunum and ileum are summarized in the table.

| Jejunum | Ileum | |

|---|---|---|

| Diameter | 4 cm (at the most proximal end) | 2 cm (at the most distal end) |

| Wall thickness | Thicker | Thinner |

| Fat in mesentery Mesentery A layer of the peritoneum which attaches the abdominal viscera to the abdominal wall and conveys their blood vessels and nerves. Peritoneum: Anatomy | Less | More |

| Circular folds | Many, best developed | Some in the proximal ileum, very few distally |

| Lymphoid tissue/Peyer patches Patches Vitiligo | Few | Many |

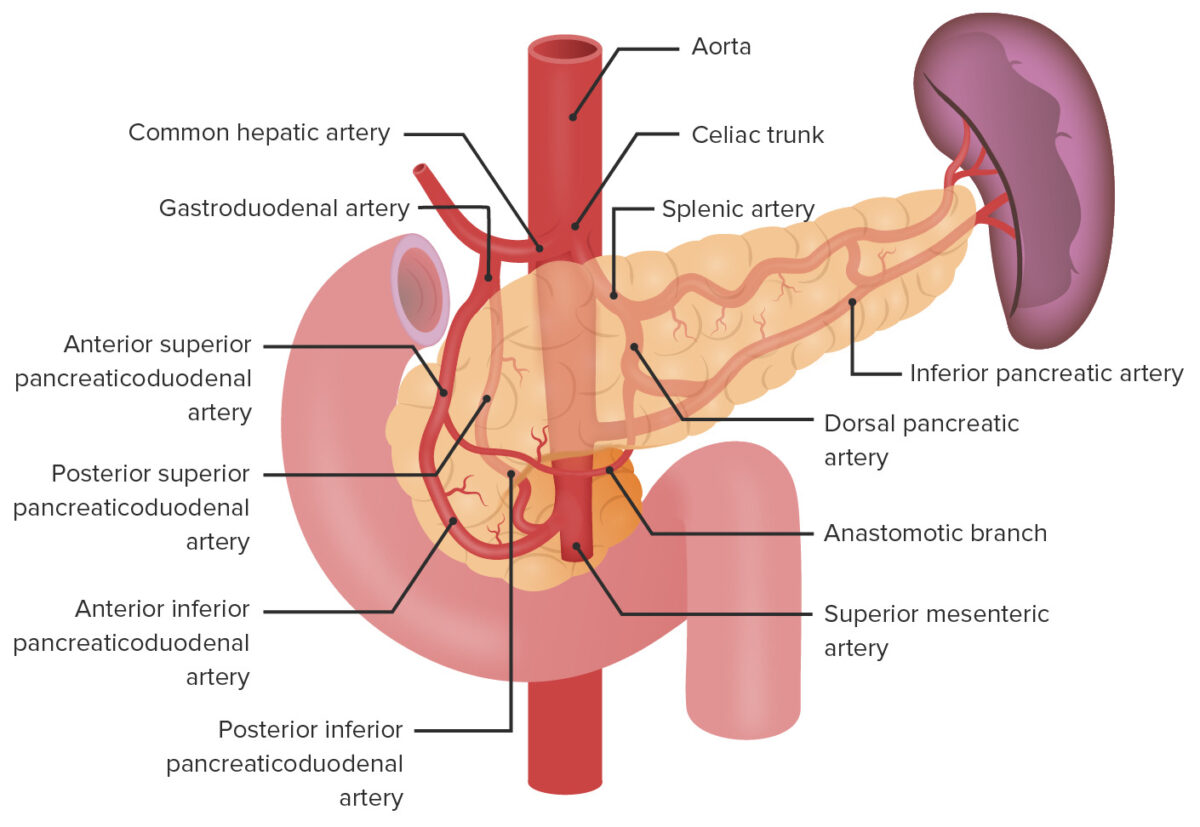

Arterial supply of the duodenum

Image by Lecturio.

Arterial supply of the jejunum and ileum

Image by Lecturio.Lacteals within the intestinal villi drain into:

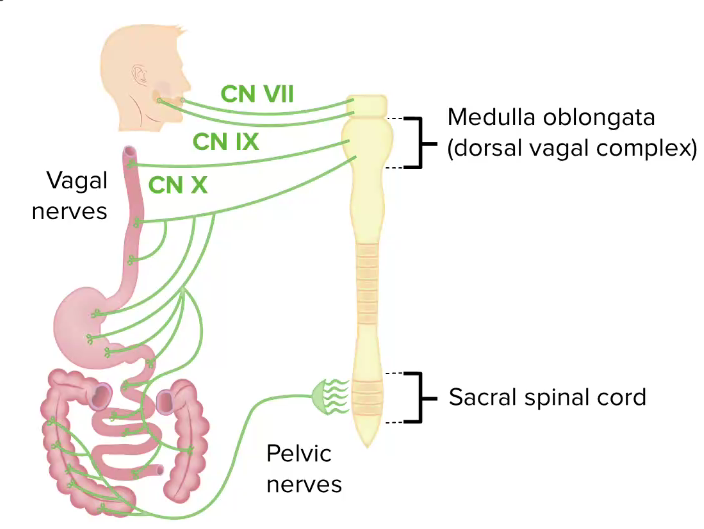

The small intestine is innervated by the ANS ANS The ans is a component of the peripheral nervous system that uses both afferent (sensory) and efferent (effector) neurons, which control the functioning of the internal organs and involuntary processes via connections with the CNS. The ans consists of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Autonomic Nervous System: Anatomy.

Parasympathetic innervation (stimulatory):

Parasympathetic innervation of the GI tract

CN: cranial nerve

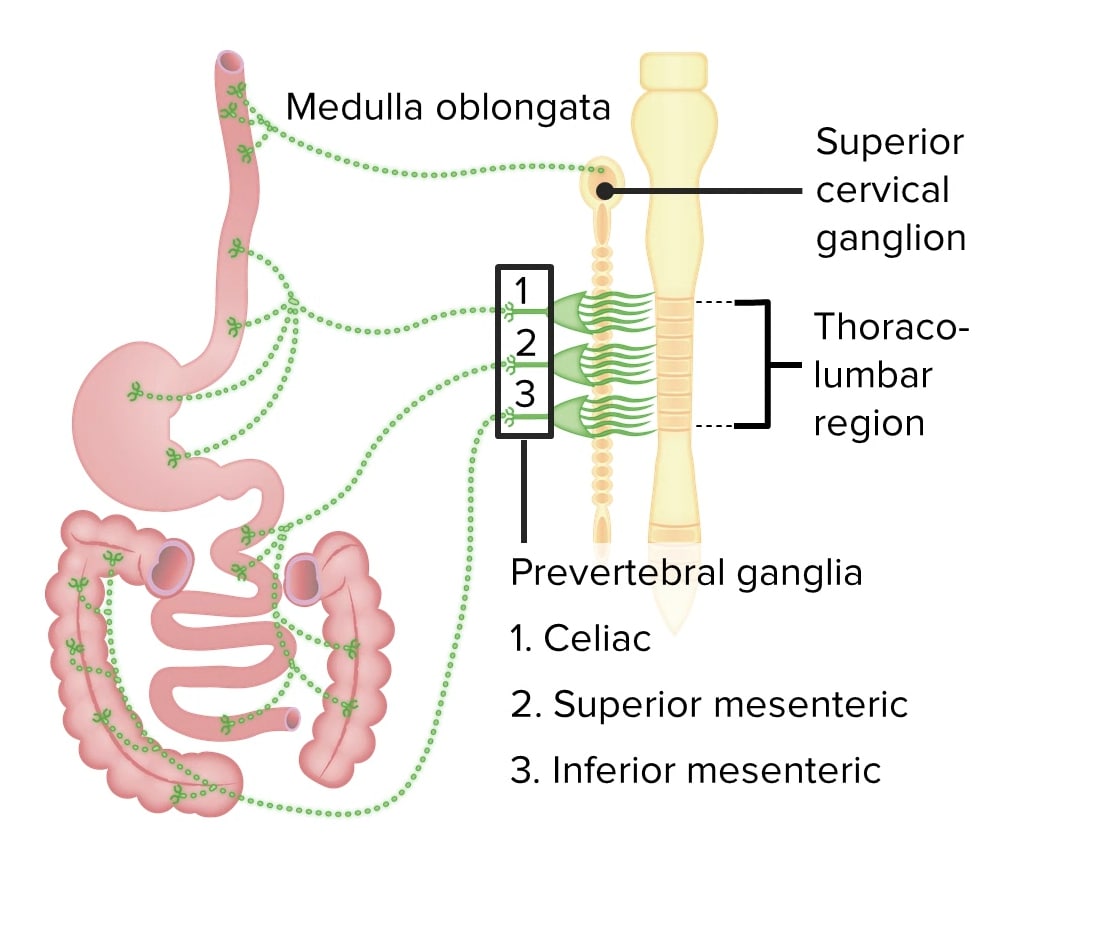

Sympathetic innervation (inhibitory):

Sympathetic innervation of the GI tract

Image by Lecturio.The small intestines are the primary site of chemical digestion Digestion Digestion refers to the process of the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food into smaller particles, which can then be absorbed and utilized by the body. Digestion and Absorption and absorption Absorption Absorption involves the uptake of nutrient molecules and their transfer from the lumen of the GI tract across the enterocytes and into the interstitial space, where they can be taken up in the venous or lymphatic circulation. Digestion and Absorption of nutrients.