Leishmania species are obligate intracellular parasites that are transmitted by an infected sandfly. The disease is endemic to Asia ASIA Spinal Cord Injuries, the Middle East, Africa, the Mediterranean, and South and Central America. Clinical presentation varies, dependent on the pathogenicity of the species and the host’s immune response. The mildest form is cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), characterized by painless skin Skin The skin, also referred to as the integumentary system, is the largest organ of the body. The skin is primarily composed of the epidermis (outer layer) and dermis (deep layer). The epidermis is primarily composed of keratinocytes that undergo rapid turnover, while the dermis contains dense layers of connective tissue. Skin: Structure and Functions ulcers. The mucocutaneous type involves more tissue destruction, causing deformities. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL), the most severe form, presents with hepatosplenomegaly Hepatosplenomegaly Cytomegalovirus, anemia Anemia Anemia is a condition in which individuals have low Hb levels, which can arise from various causes. Anemia is accompanied by a reduced number of RBCs and may manifest with fatigue, shortness of breath, pallor, and weakness. Subtypes are classified by the size of RBCs, chronicity, and etiology. Anemia: Overview and Types, thrombocytopenia Thrombocytopenia Thrombocytopenia occurs when the platelet count is < 150,000 per microliter. The normal range for platelets is usually 150,000-450,000/µL of whole blood. Thrombocytopenia can be a result of decreased production, increased destruction, or splenic sequestration of platelets. Patients are often asymptomatic until platelet counts are < 50,000/µL. Thrombocytopenia, and fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever. Management is based on the clinical severity and patient's immune status. Some cutaneous lesions spontaneously resolve or require local therapy. Systemic treatment ( amphotericin B Amphotericin B Macrolide antifungal antibiotic produced by streptomyces nodosus obtained from soil of the orinoco river region of venezuela. Polyenes), however, is needed for VL.

Last updated: Sep 19, 2022

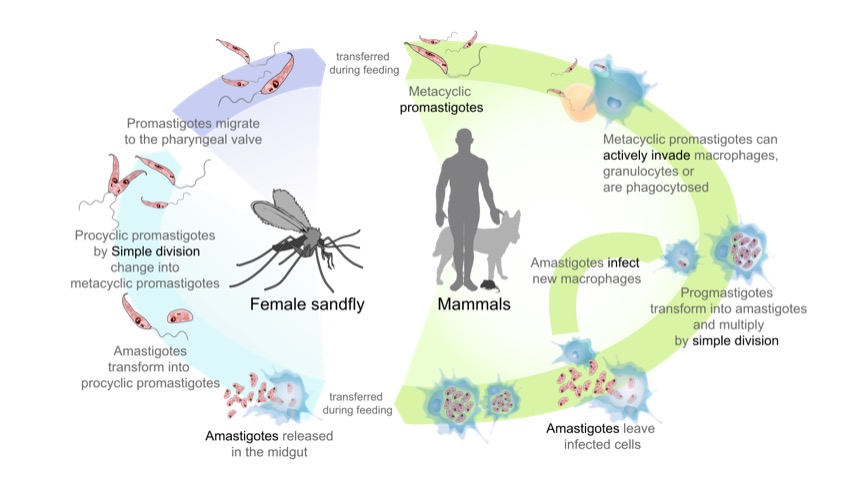

In the sandfly:

In humans:

The life cycle of the parasites from the genus Leishmania, the cause of the disease leishmaniasis:

On the left side (start at the bottom): Sandfly acquires amastigotes from an infected mammal. Amastigotes transform into extracellular promastigotes that multiply in the midgut. Eventually, the promastigotes migrate to the sandfly proboscis, ready to be transferred to a host when the sandfly bites.

On the right side (start at the top): Promastigotes are transferred to mammals, and are phagocytosed by macrophages. In the cell, promastigotes transform into amastigotes and multiply. Affected cell ruptures and amastigotes spread to infect other cells.

Skin ulcer due to leishmaniasis noted on the hand of an adult from Central America

Image: “Skin ulcer due to leishmaniasis” by CDC/ Dr. D.S. Martin. License: Public Domain

Diffuse or disseminated CL: seen in a patient with human immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV)

Image: “Diffuse or disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis” by Rotterdam Centre for Tropical Medicine, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. License: CC BY 4.0

Cutaneous leishmaniasis: leishmaniasis ulcer on left forearm

Image: “Leishmaniasis ulcer on left forearm” by Layne Harris. License: Public Domain

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: painful mucosal lesions on the palate

Image: “Healing of lesion” by Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, E.S.I.C Dental College & Hospital, Rohini, Delhi 110089, India. License: CC BY 3.0

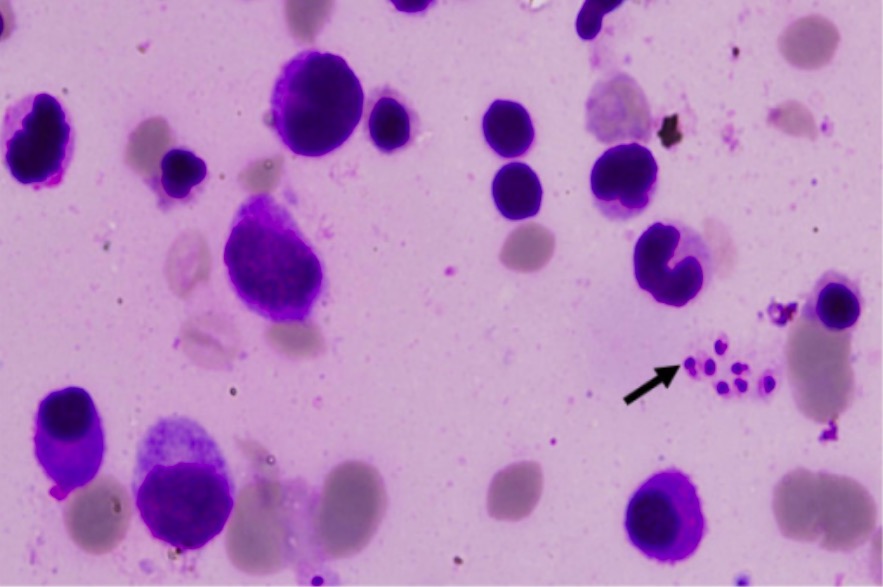

Visceral leishmaniasis: bone marrow slide showing Leishman-Donovan bodies (arrow)

Image: “Leishman-Donovan bodies” by Department of Medicine, Maulana Azad Medical College, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi, 110002, India. License: CC BY 2.0

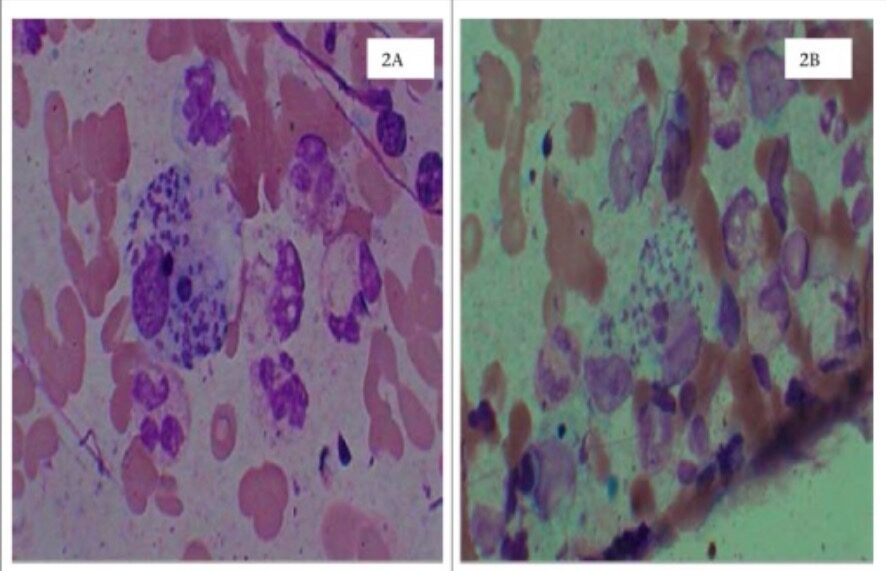

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

2A: dermal skin scrapings in Wright’s stain showing Leishman-Donovan bodies (amastigotes) in the macrophage

2B: dermal skin scrapings in Leishman’s stain

| Giardia Giardia A genus of flagellate intestinal eukaryotes parasitic in various vertebrates, including humans. Characteristics include the presence of four pairs of flagella arising from a complicated system of axonemes and cysts that are ellipsoidal to ovoidal in shape. Nitroimidazoles | Leishmania | Trypanosoma | Trichomonas Trichomonas A genus of parasitic flagellate eukaryotes distinguished by the presence of four anterior flagella, an undulating membrane, and a trailing flagellum. Nitroimidazoles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics |

|

|

|

|

| Forms |

|

|

|

|

| Transmission |

|

|

|

Sexually transmitted |

| Clinical | Giardiasis Giardiasis An infection of the small intestine caused by the flagellated protozoan giardia. It is spread via contaminated food and water and by direct person-to-person contact. Giardia/Giardiasis | Leishmaniasis |

|

Trichomoniasis |

| Diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

| Treatment |

|

Depends on the clinical syndrome:

|

Depends on the clinical disease:

|

|

| Prevention |

|

|

|

|

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

DFA: direct immunofluorescence assay

NAAT: nucleic acid amplification assay

PCR: polymerase chain reaction

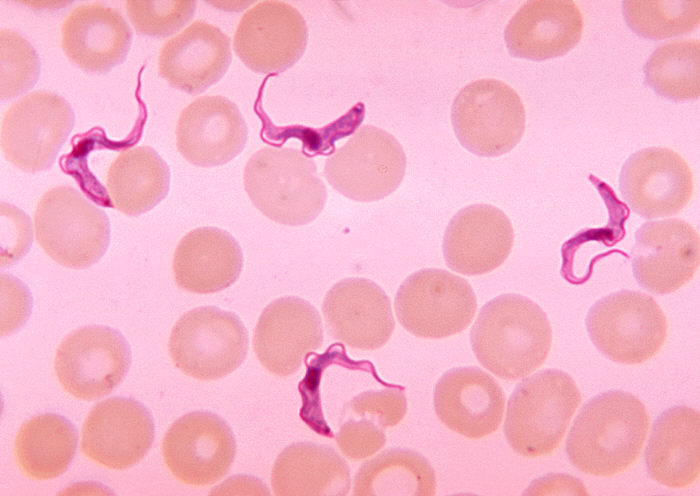

Blood smear demonstrating Trypanosoma trypomastigotes

Image: “Ms. Michaels forms” by CDC/Dr. Myron G. Schultz. License: Public Domain

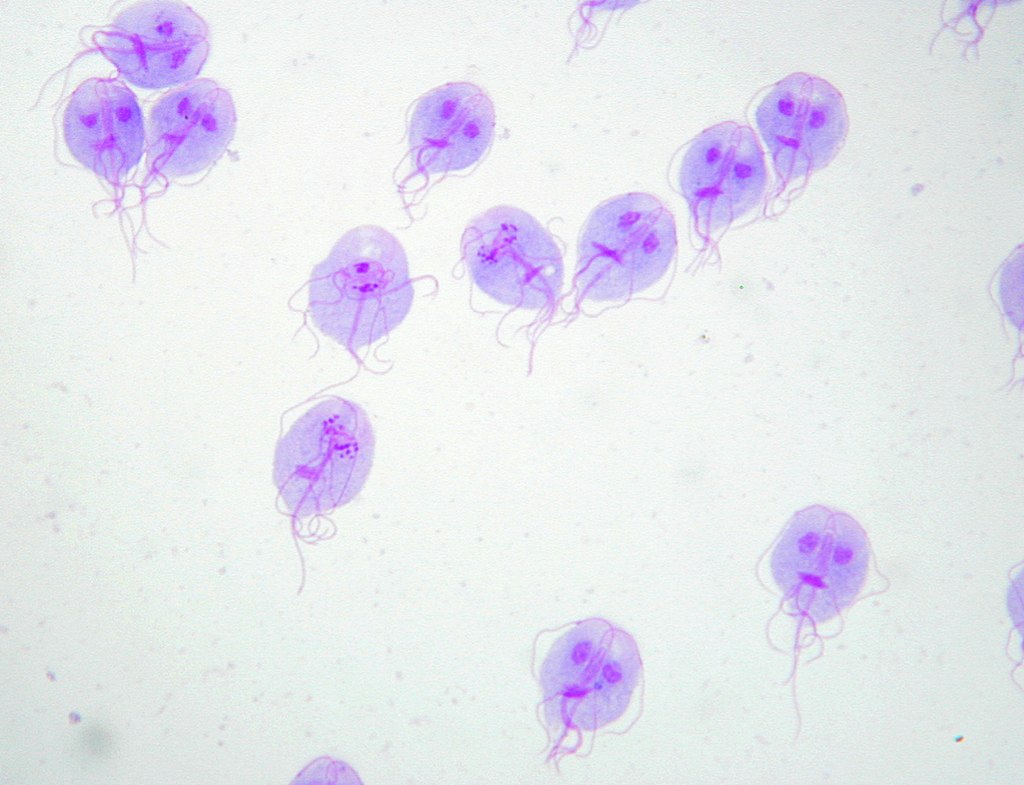

Giemsa’s stain of Giardia lamblia trophozoites

Image: “Trophozoites of Giardia lamblia” by Eva Nohýnková, Department of Tropical Medicine, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University in Prague and Hospital Bulovka, Czech Republic. License: CC BY 4.0

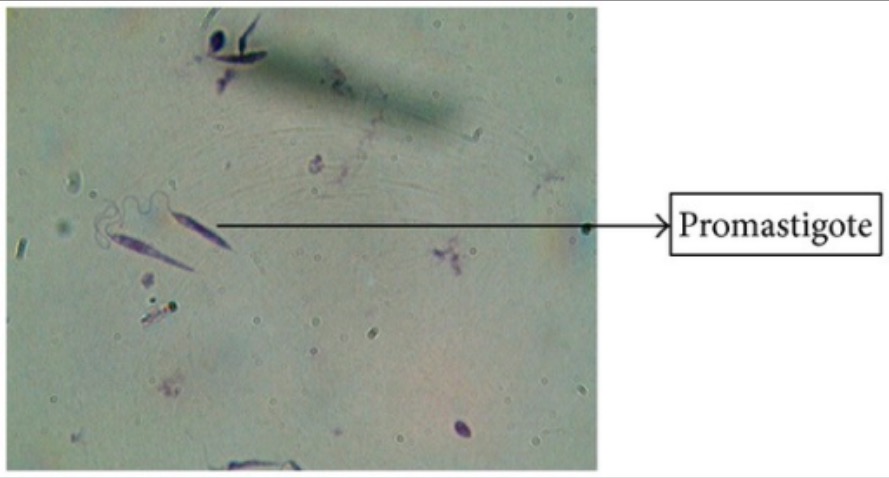

Giemsa’s stain of Leishmania promastigotes

Image: “Giemsa stain” by Arriyadh Community College, King Saud University, P.O. Box 28095, Riyadh 11437, Saudi Arabia. License: CC BY 3.0

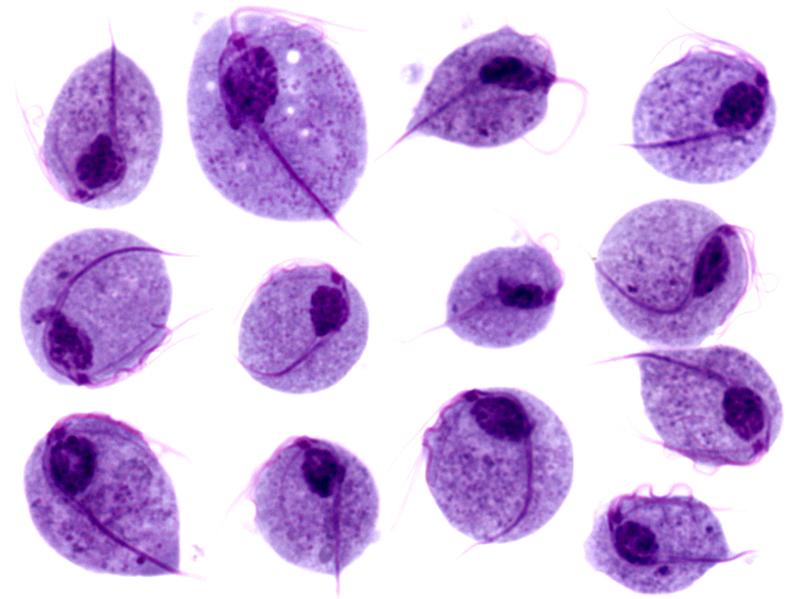

Microscopic images of Trichomonas vaginalis trophozoites

Image: “Trichomonas protozoa” by isis325. License: CC BY 2.0.