Ascites is the pathologic accumulation of fluid within the peritoneal cavity Peritoneal Cavity The space enclosed by the peritoneum. It is divided into two portions, the greater sac and the lesser sac or omental bursa, which lies behind the stomach. The two sacs are connected by the foramen of winslow, or epiploic foramen. Peritoneum: Anatomy that occurs due to an osmotic and/or hydrostatic pressure Hydrostatic pressure The pressure due to the weight of fluid. Edema imbalance secondary to portal hypertension Portal hypertension Portal hypertension is increased pressure in the portal venous system. This increased pressure can lead to splanchnic vasodilation, collateral blood flow through portosystemic anastomoses, and increased hydrostatic pressure. There are a number of etiologies, including cirrhosis, right-sided congestive heart failure, schistosomiasis, portal vein thrombosis, hepatitis, and Budd-Chiari syndrome. Portal Hypertension ( cirrhosis Cirrhosis Cirrhosis is a late stage of hepatic parenchymal necrosis and scarring (fibrosis) most commonly due to hepatitis C infection and alcoholic liver disease. Patients may present with jaundice, ascites, and hepatosplenomegaly. Cirrhosis can also cause complications such as hepatic encephalopathy, portal hypertension, portal vein thrombosis, and hepatorenal syndrome. Cirrhosis, heart failure Heart Failure A heterogeneous condition in which the heart is unable to pump out sufficient blood to meet the metabolic need of the body. Heart failure can be caused by structural defects, functional abnormalities (ventricular dysfunction), or a sudden overload beyond its capacity. Chronic heart failure is more common than acute heart failure which results from sudden insult to cardiac function, such as myocardial infarction. Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Return (TAPVR)) or non-portal hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension ( hypoalbuminemia Hypoalbuminemia A condition in which albumin level in blood (serum albumin) is below the normal range. Hypoalbuminemia may be due to decreased hepatic albumin synthesis, increased albumin catabolism, altered albumin distribution, or albumin loss through the urine (albuminuria). Nephrotic Syndrome in Children, malignancy Malignancy Hemothorax, infection). Patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship often present with progressive abdominal distention Abdominal distention Megacolon and weight gain. Abdominal exam may reveal shifting dullness and a positive fluid wave. Diagnosis is established with an ultrasound, and etiologies can be distinguished by ascitic fluid analysis from paracentesis Paracentesis A procedure in which fluid is withdrawn from a body cavity or organ via a trocar and cannula, needle, or other hollow instrument. Portal Hypertension. Treatment involves dietary sodium Sodium A member of the alkali group of metals. It has the atomic symbol na, atomic number 11, and atomic weight 23. Hyponatremia restriction, diuretics Diuretics Agents that promote the excretion of urine through their effects on kidney function. Heart Failure and Angina Medication, and treatment of the underlying cause.

Last updated: Jan 16, 2024

Ascites is caused by an osmotic and/or hydrostatic pressure Hydrostatic pressure The pressure due to the weight of fluid. Edema imbalance often secondary to:

Portal hypertension-related ascites:

Non-portal hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension–related ascites:

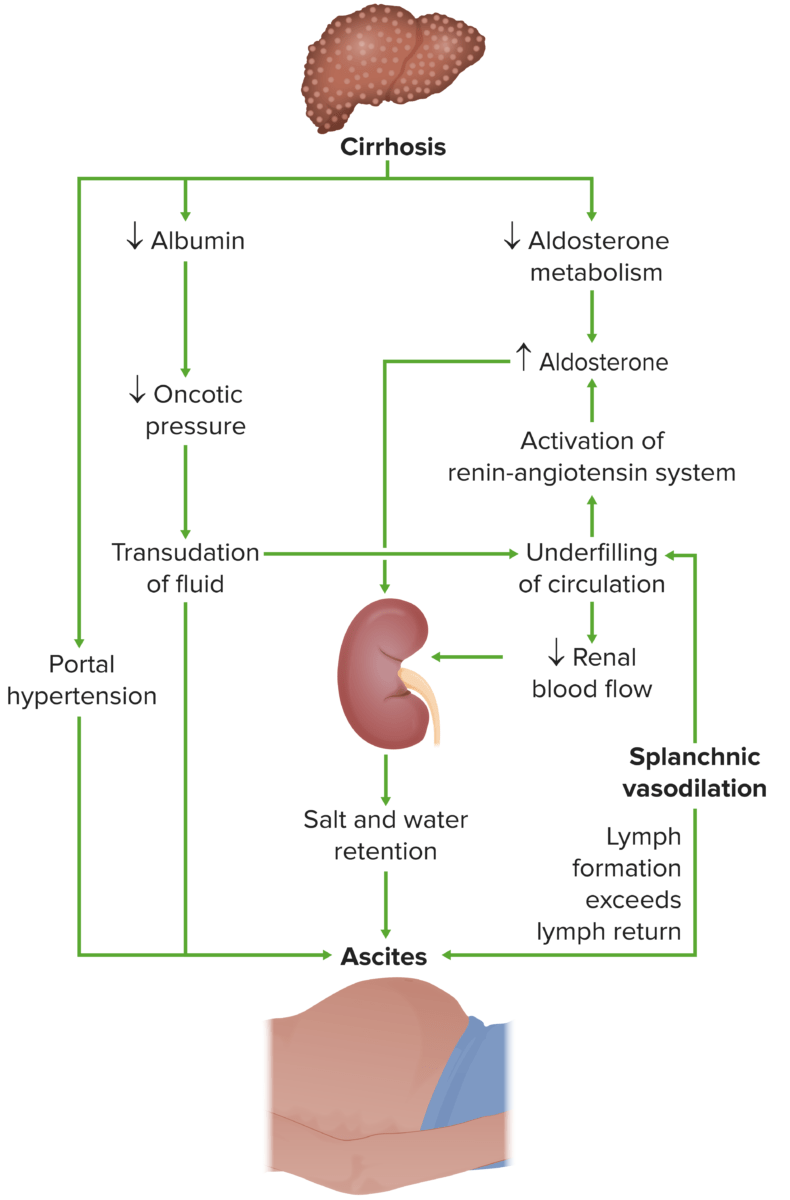

Pathogenesis of ascites:

Ascites development due to cirrhosis is caused by multiple factors that cause a hydrostatic and/or oncotic imbalance.

The next step requires analysis of the ascitic fluid.

| SAAG > 1.1 g/dL: suggestive of portal hypertension Portal hypertension Portal hypertension is increased pressure in the portal venous system. This increased pressure can lead to splanchnic vasodilation, collateral blood flow through portosystemic anastomoses, and increased hydrostatic pressure. There are a number of etiologies, including cirrhosis, right-sided congestive heart failure, schistosomiasis, portal vein thrombosis, hepatitis, and Budd-Chiari syndrome. Portal Hypertension | SAAG < 1.1 g/dL: non-hypertension–related causes |

|---|---|

|

|

Ascites secondary to hepatic cirrhosis being drained via paracentesis

Image: “Draining ascites, secondary to hepatic cirrhosis” by John Campbell. License: Public Domain

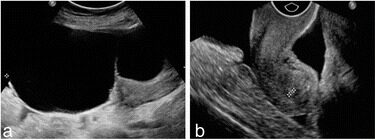

A 63-year-old woman with pelvic mass found by physical examination:

a) A 133 mm x 69 mm x 169 mm well-circumscribed mixed mass was detected in the right ovary by ultrasound examination.

b) Ultrasound detected ascites in the pelvis.

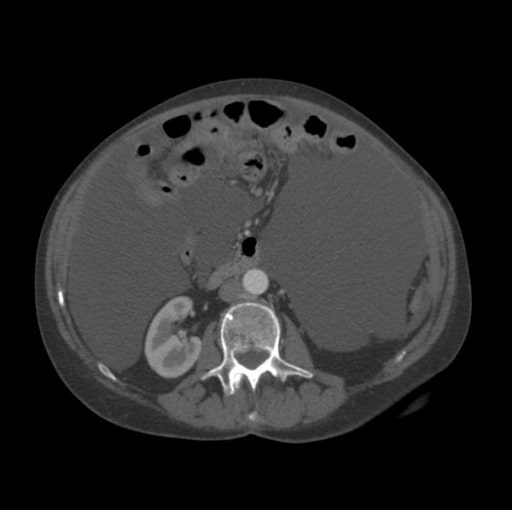

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen showing significant ascites (large, homogenous gray areas)

Image: “CT scan of the abdomen showing ascites” by Department of Gastroenterology, North Cheshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Warrington, UK. License: CC BY 2.0The figure below summarizes how to approach treatment in a patient with ascites:

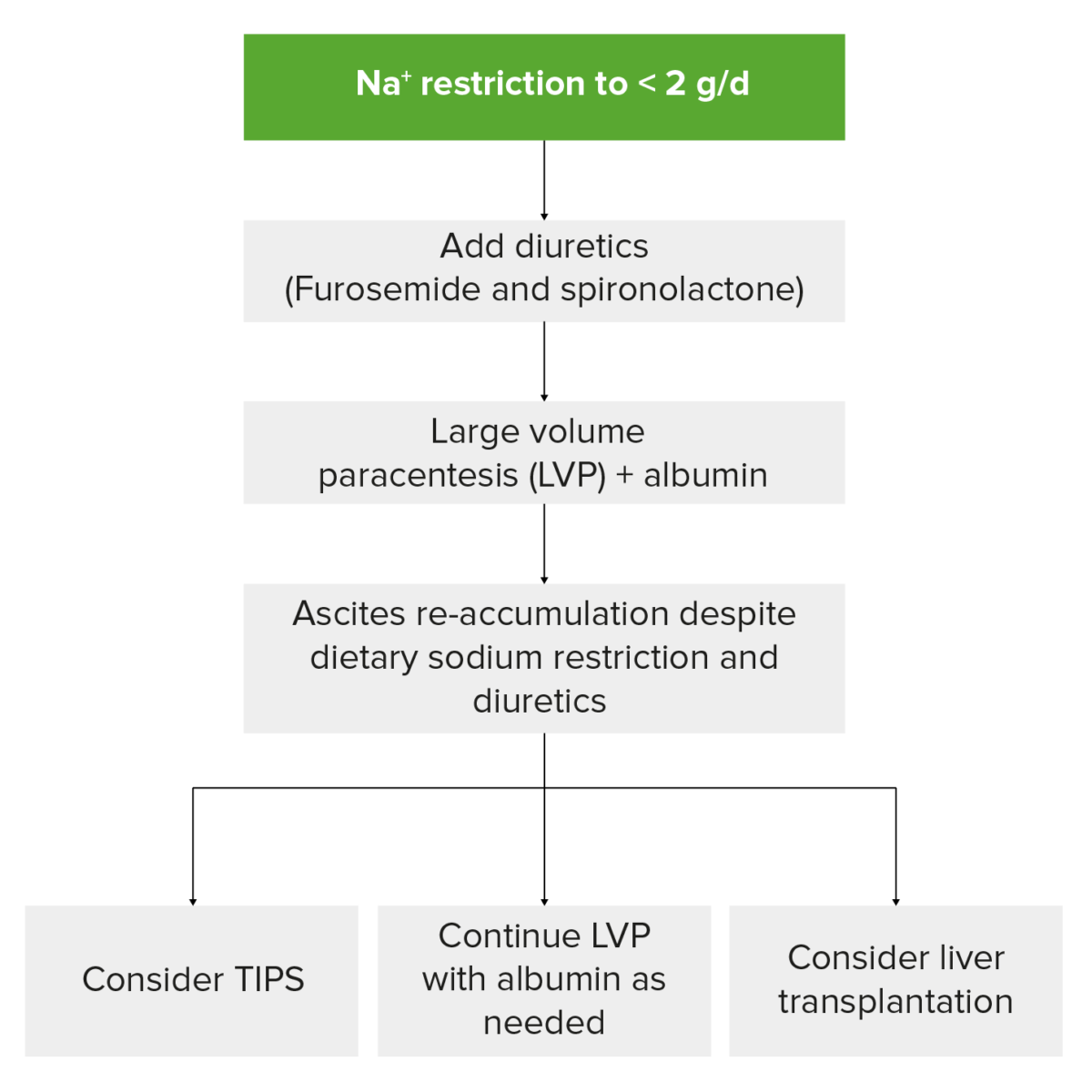

Management of refractory ascites

Image by Lecturio.