Mallory-Weiss syndrome (MWS) is bleeding from longitudinal mucosal lacerations (tears) in the distal esophagus and proximal stomach caused by a sudden rise in intraluminal esophageal pressure with forceful or recurrent vomiting. Hematemesis is due to bleeding from submucosal blood vessels and is self-limited in 80%–90% of patients. Diagnosis is made by taking a history and performing upper GI endoscopy. Treatment includes gastric acid suppression, endoscopic intervention, and angiotherapy if there is active bleeding. Blood transfusions and surgery are not usually required.

Last updated: May 28, 2025

Risk factors

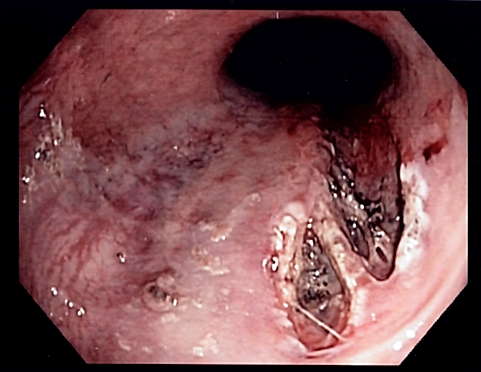

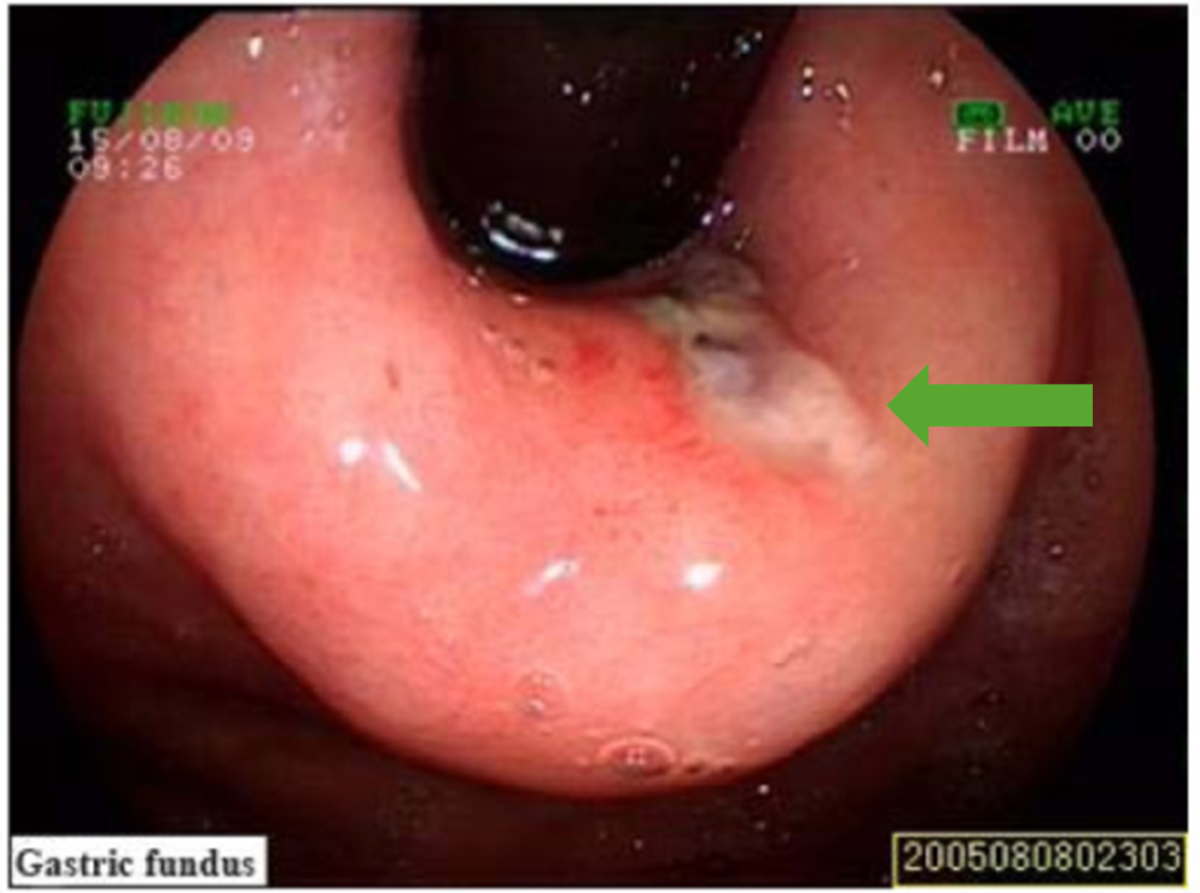

Diagnosis is established by endoscopy Endoscopy Procedures of applying endoscopes for disease diagnosis and treatment. Endoscopy involves passing an optical instrument through a small incision in the skin i.e., percutaneous; or through a natural orifice and along natural body pathways such as the digestive tract; and/or through an incision in the wall of a tubular structure or organ, i.e. Transluminal, to examine or perform surgery on the interior parts of the body. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD), which shows a longitudinal tear (usually single) limited to the mucosa and submucosa at the gastroesophageal junction Gastroesophageal junction The area covering the terminal portion of esophagus and the beginning of stomach at the cardiac orifice. Esophagus: Anatomy. The muscular layer is NOT involved(in contrast to Boerhaave syndrome Boerhaave Syndrome Esophageal Perforation).

Endoscopic image of a Mallory-Weiss tear

Image: “Mallory Weiss Tear” by Samir. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Mallory-Weiss tear (green arrow) as visualized on esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

Image: “Mallory-Weiss syndrome” by Zhao Y, Wang L, Si J. License: CC BY 3.0, edited by Lecturio.