Epiglottitis (or "supraglottitis") is an inflammation of the epiglottis and adjacent supraglottic structures. The majority of cases are caused by bacterial infection; however, several viral and fungal pathogens have been identified, depending on the patient’s immune status and age. Symptoms are rapid in onset and severe. Without treatment, epiglottitis can cause life-threatening airway obstruction that presents with difficulty breathing, stridor, and cyanosis. Diagnosis is mainly clinical but can be confirmed by laryngoscopy. The focus of treatment is airway Airway ABCDE Assessment management and administration of antibiotics.

Last updated: May 12, 2025

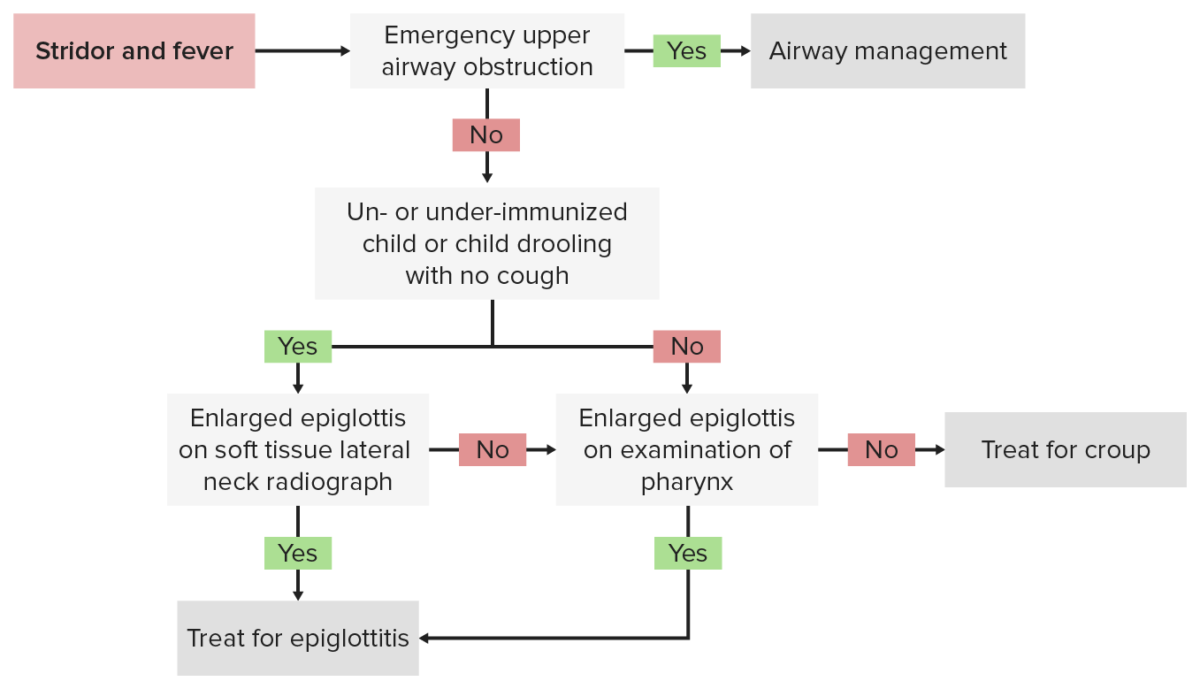

Diagnostic algorithm for epiglottitis

Image by Lecturio.

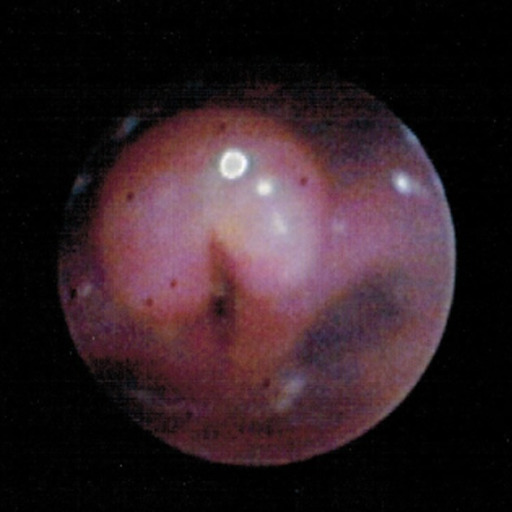

Bronchoscopy image shows a swollen and inflated epiglottis and arytenoids along with aryepiglottic folds consistent with acute epiglottitis (supraglottitis).

Image: “Bronchoscopy” by Department of Pediatrics, University of Toledo Toledo, Ohio, United States of America. License: CC BY 3.0

Acute epiglottitis presenting with the “thumb sign” in a lateral neck x-ray

Image: “Acute epiglottitis; Lateral view in X-ray imaging.” by Med Chaos – Own work. License: CC0Prognosis Prognosis A prediction of the probable outcome of a disease based on a individual’s condition and the usual course of the disease as seen in similar situations. Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas is good if diagnosed and treated immediately but the disease can lead to death if there is acute and untreated airway Airway ABCDE Assessment obstruction.

Complications of epiglottitis