Laryngomalacia and tracheomalacia are the most common upper airway Airway ABCDE Assessment conditions that produce stridor in newborns. Laryngomalacia and tracheomalacia tend to present in the 1st 2 weeks of life, with symptoms ranging from stridor to respiratory distress. The symptoms are caused by narrowing of the airway Airway ABCDE Assessment, which may be due to weakened cartilage Cartilage Cartilage is a type of connective tissue derived from embryonic mesenchyme that is responsible for structural support, resilience, and the smoothness of physical actions. Perichondrium (connective tissue membrane surrounding cartilage) compensates for the absence of vasculature in cartilage by providing nutrition and support. Cartilage: Histology, redundant tissue, external compression External Compression Blunt Chest Trauma, or hypotonia Hypotonia Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy of the affected area. Most cases are congenital, but tracheomalacia can be acquired in children or adults. Diagnosis is based on history, clinical findings, and confirmation by laryngoscopy or bronchoscopy. Treatment is supportive or surgical, depending on the severity. The majority of cases are self-limiting Self-Limiting Meningitis in Children and resolve by 2–3 years of age, but some tracheomalacia cases can persist into adulthood.

Last updated: Jun 27, 2025

Laryngomalacia is softening of or redundancy of supraglottic structures leading to collapse and narrowing of the airway Airway ABCDE Assessment during inspiration Inspiration Ventilation: Mechanics of Breathing.

Tracheomalacia is an abnormality in tracheal compliance Compliance Distensibility measure of a chamber such as the lungs (lung compliance) or bladder. Compliance is expressed as a change in volume per unit change in pressure. Veins: Histology caused by a variety of factors, resulting in the dynamic airway Airway ABCDE Assessment narrowing.

Laryngomalacia:

Tracheomalacia:

Laryngomalacia (not exactly known) presumed causes:

Tracheomalacia:

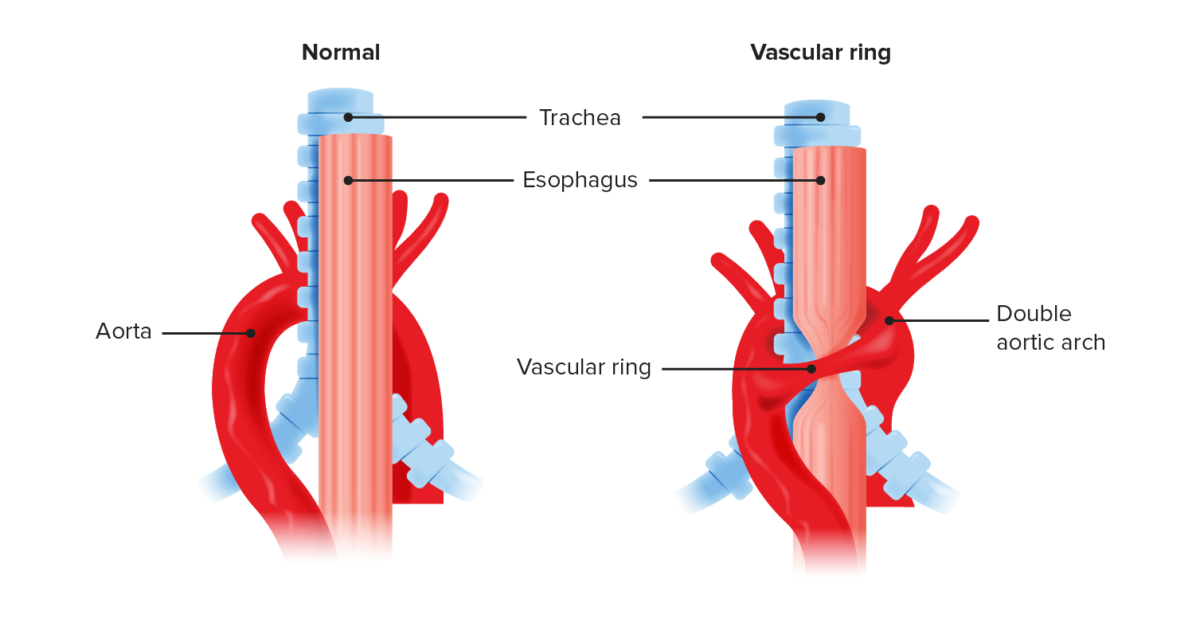

Anatomic recreation of a vascular ring compared to normal anatomy:

Double aortic arch causes compression of the trachea and esophagus. Vascular rings often compress the trachea, leading to a degree of tracheomalacia.

Laryngomalacia:

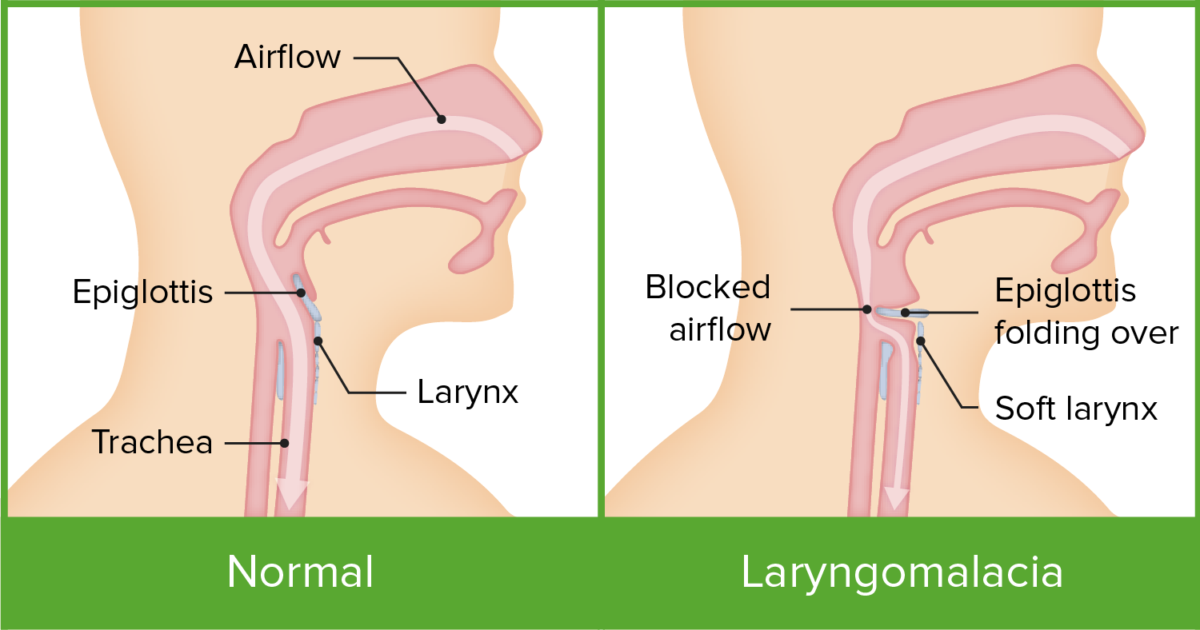

Anatomic and physiologic differences between a healthy larynx and laryngomalacia

Image by Lecturio.

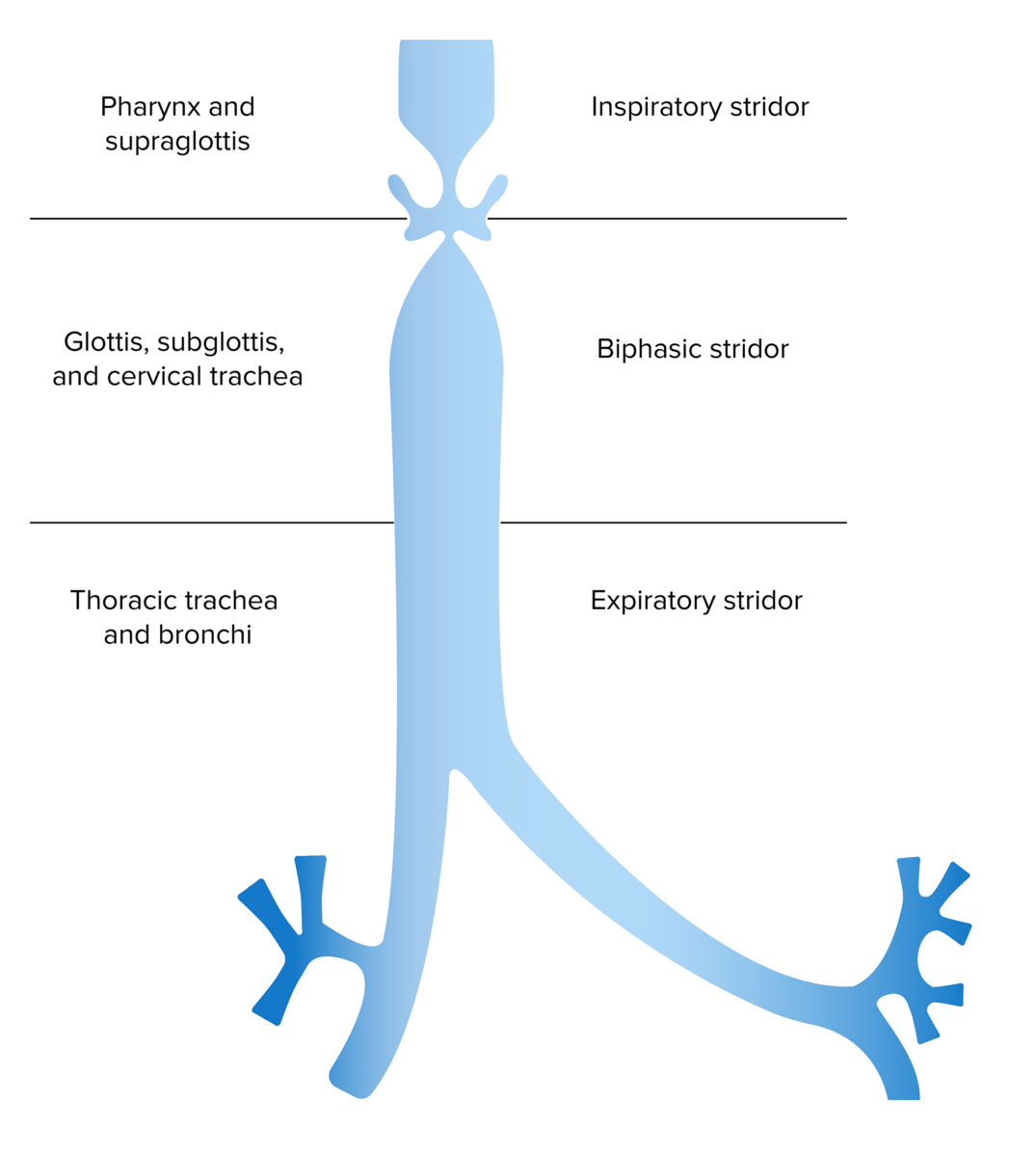

Anatomic location of obstruction based on inspiratory versus expiratory stridor

Image by Lecturio.Tracheomalacia:

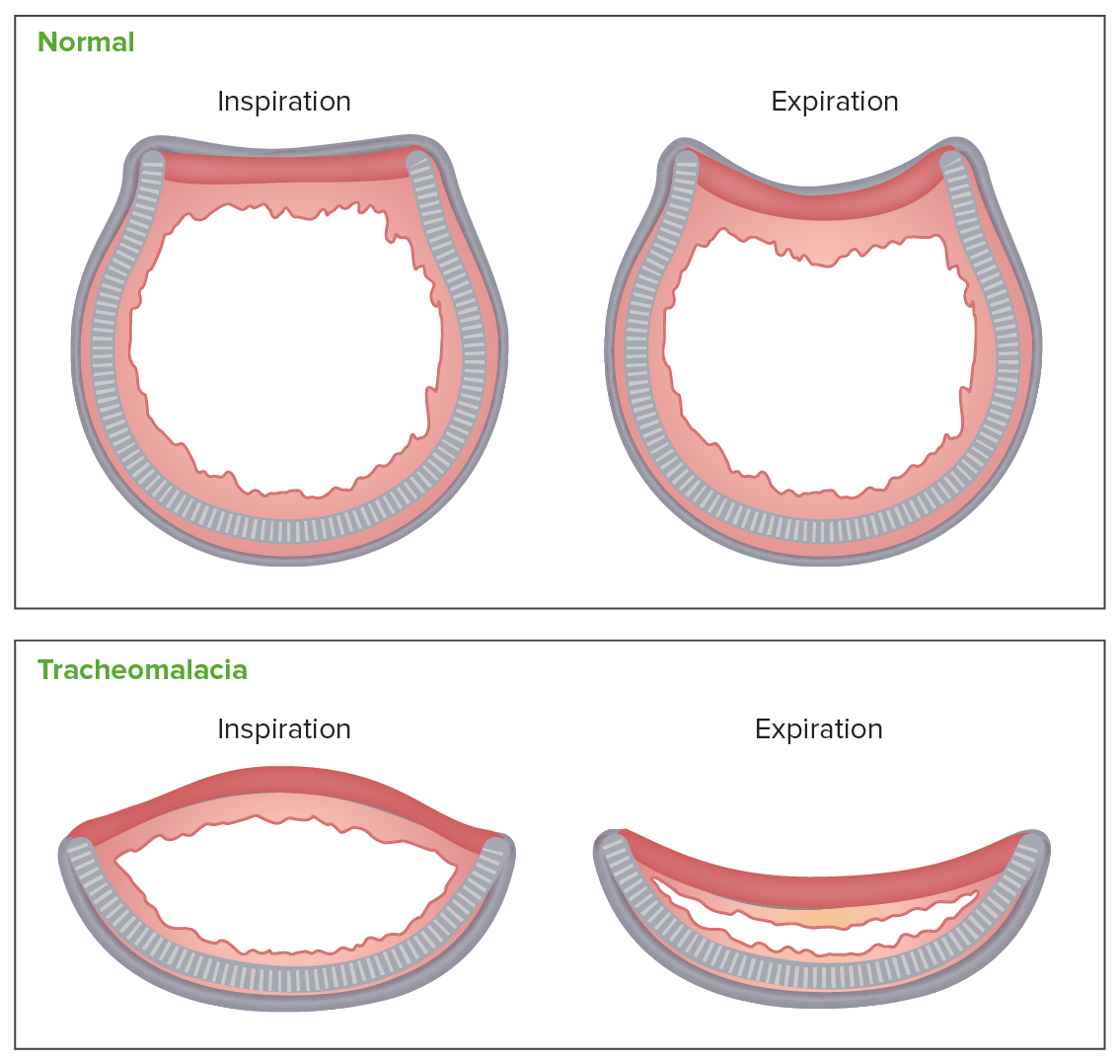

Cross-sectional view of anatomic changes during inspiration and expiration in a healthy trachea versus tracheomalacia:

Due to the structural laxity of the cartilage in tracheomalacia, the already significantly reduced airway lumen further narrows during expiration.

Laryngomalacia:

Tracheomalacia:

Plain X-ray X-ray Penetrating electromagnetic radiation emitted when the inner orbital electrons of an atom are excited and release radiant energy. X-ray wavelengths range from 1 pm to 10 nm. Hard x-rays are the higher energy, shorter wavelength x-rays. Soft x-rays or grenz rays are less energetic and longer in wavelength. The short wavelength end of the x-ray spectrum overlaps the gamma rays wavelength range. The distinction between gamma rays and x-rays is based on their radiation source. Pulmonary Function Tests of the neck Neck The part of a human or animal body connecting the head to the rest of the body. Peritonsillar Abscess and chest:

Airway Airway ABCDE Assessment fluoroscopy Fluoroscopy Production of an image when x-rays strike a fluorescent screen. X-rays:

Computed tomography (CT) scan:

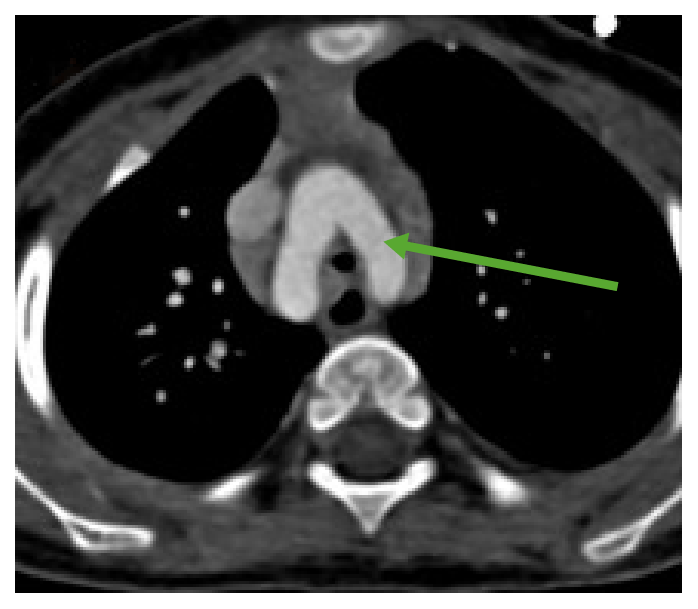

A CT scan showing a double aortic arch (arrow) compressing the trachea

Image: “Double aortic arch” by the Shandong Medical Imaging Research Institute, Shandong University, Ji’nan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China. License: CC BY 4.0, edited by Lecturio.

Endoscopic appearance of laryngomalacia

Image: “Endoscopic features of laryngomalacia” by Wong Birgitta Yee-Hang et al. License: CC BY 4.0.

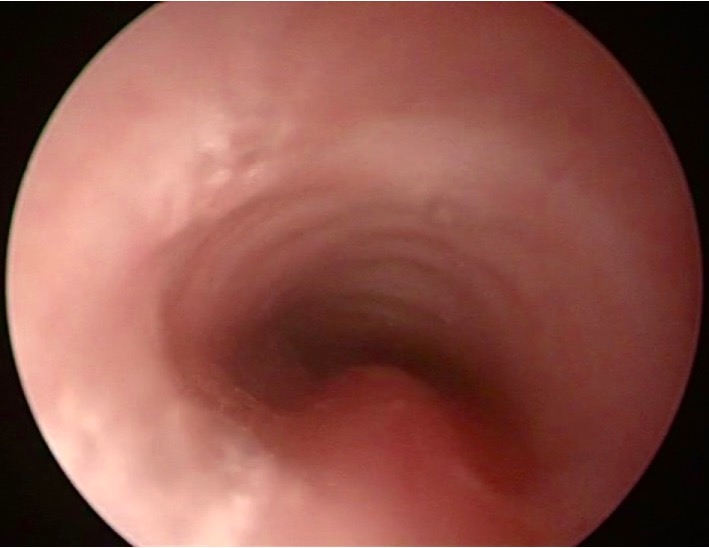

Bronchoscopy picture of tracheomalacia: Notice the narrowing of the lumen.

Image: “Bronchoscopy picture of tracheomalacia” by Quen Mok. License: CC BY 4.0.Mild:

Moderate/severe:

Children:

Adults: