Gastroenteritis is inflammation Inflammation Inflammation is a complex set of responses to infection and injury involving leukocytes as the principal cellular mediators in the body's defense against pathogenic organisms. Inflammation is also seen as a response to tissue injury in the process of wound healing. The 5 cardinal signs of inflammation are pain, heat, redness, swelling, and loss of function. Inflammation of the stomach Stomach The stomach is a muscular sac in the upper left portion of the abdomen that plays a critical role in digestion. The stomach develops from the foregut and connects the esophagus with the duodenum. Structurally, the stomach is C-shaped and forms a greater and lesser curvature and is divided grossly into regions: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. Stomach: Anatomy and intestines, commonly caused by infections Infections Invasion of the host organism by microorganisms or their toxins or by parasites that can cause pathological conditions or diseases. Chronic Granulomatous Disease from bacteria Bacteria Bacteria are prokaryotic single-celled microorganisms that are metabolically active and divide by binary fission. Some of these organisms play a significant role in the pathogenesis of diseases. Bacteriology, viruses Viruses Minute infectious agents whose genomes are composed of DNA or RNA, but not both. They are characterized by a lack of independent metabolism and the inability to replicate outside living host cells. Virology, or parasites. Transmission may be foodborne, fecal-oral, or through animal contact. Common clinical features include abdominal pain Abdominal Pain Acute Abdomen, diarrhea Diarrhea Diarrhea is defined as ≥ 3 watery or loose stools in a 24-hour period. There are a multitude of etiologies, which can be classified based on the underlying mechanism of disease. The duration of symptoms (acute or chronic) and characteristics of the stools (e.g., watery, bloody, steatorrheic, mucoid) can help guide further diagnostic evaluation. Diarrhea, vomiting Vomiting The forcible expulsion of the contents of the stomach through the mouth. Hypokalemia, fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever, and dehydration Dehydration The condition that results from excessive loss of water from a living organism. Volume Depletion and Dehydration. Diagnostic testing with stool analysis or culture is not always required, but can help determine the etiology in certain circumstances. The majority of cases of gastroenteritis are self-limited; therefore, the only required treatment is supportive therapy (fluids). However, antibiotics are indicated in severe cases.

Last updated: May 16, 2024

| Mechanism of diarrhea Diarrhea Diarrhea is defined as ≥ 3 watery or loose stools in a 24-hour period. There are a multitude of etiologies, which can be classified based on the underlying mechanism of disease. The duration of symptoms (acute or chronic) and characteristics of the stools (e.g., watery, bloody, steatorrheic, mucoid) can help guide further diagnostic evaluation. Diarrhea | Non-inflammatory ( adhesion Adhesion The process whereby platelets adhere to something other than platelets, e.g., collagen; basement membrane; microfibrils; or other ‘foreign’ surfaces. Coagulation Studies, enterotoxin Enterotoxin Substances that are toxic to the intestinal tract causing vomiting, diarrhea, etc. ; most common enterotoxins are produced by bacteria. Diarrhea) | Inflammatory (invasion, cytotoxin) | Penetrating (invades lymphatics) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation | Watery diarrhea Watery diarrhea Rotavirus | Dysentery (blood or mucus) or inflammatory diarrhea Diarrhea Diarrhea is defined as ≥ 3 watery or loose stools in a 24-hour period. There are a multitude of etiologies, which can be classified based on the underlying mechanism of disease. The duration of symptoms (acute or chronic) and characteristics of the stools (e.g., watery, bloody, steatorrheic, mucoid) can help guide further diagnostic evaluation. Diarrhea | Enteric fever Enteric Fever Typhoid (or enteric) fever is a severe, systemic bacterial infection classically caused by the facultative intracellular and Gram-negative bacilli Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi (S. Typhimurium, formerly S. typhi). S. paratyphi serotypes A, B, or C can cause a similar syndrome. Enteric Fever (Typhoid Fever) |

| Stool findings |

|

|

Fecal mononuclear leukocytes Leukocytes White blood cells. These include granular leukocytes (basophils; eosinophils; and neutrophils) as well as non-granular leukocytes (lymphocytes and monocytes). White Myeloid Cells: Histology |

| Pathogen involved |

|

|

|

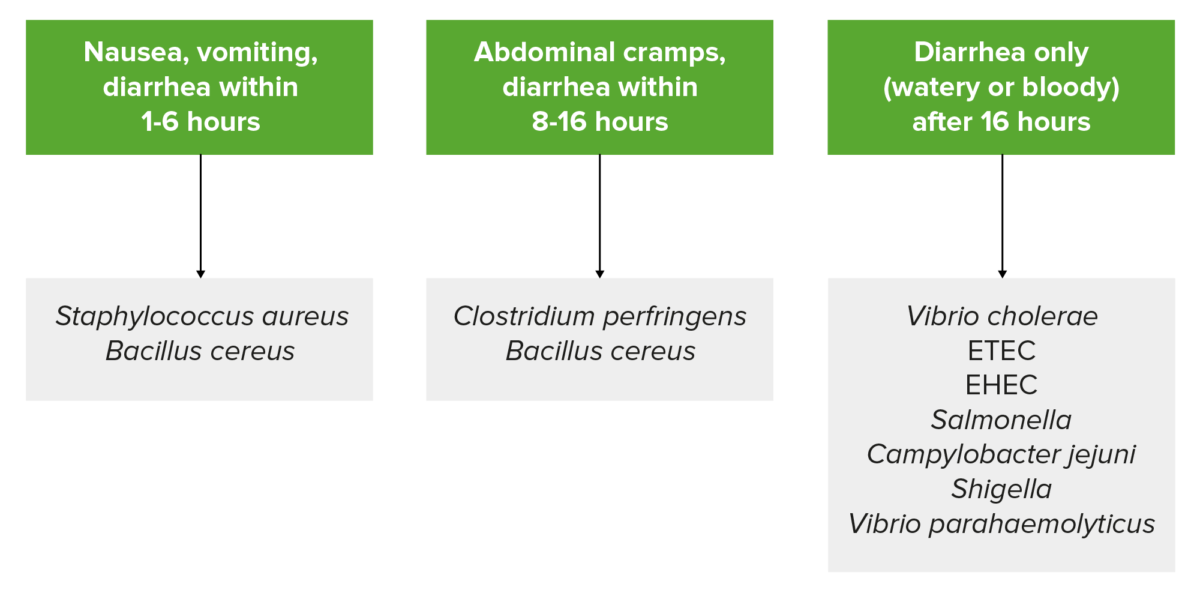

Summary of common symptoms and incubation periods based on the pathogen:

Bacillus cereus is listed twice since it produces two types of food-borne illness due to different enterotoxins. Emetic-type illness has an incubation of around 1‒6 hours, and diarrheal-type illness has an incubation period of 8‒16 hours.

Note: this is a generalization, and patient presentation can vary.

ETEC: Enterotoxigenic E. coli

EHEC: Enterohemorrhagic E. coli

| Organism | Characteristic features |

|---|---|

| Bacillus cereus Bacillus cereus A species of rod-shaped bacteria that is a common soil saprophyte. Its spores are widespread and multiplication has been observed chiefly in foods. Contamination may lead to food poisoning. Bacillus |

|

| Staphylococcus aureus Staphylococcus aureus Potentially pathogenic bacteria found in nasal membranes, skin, hair follicles, and perineum of warm-blooded animals. They may cause a wide range of infections and intoxications. Brain Abscess |

|

| Clostridioides difficile |

|

| Salmonella Salmonella Salmonellae are gram-negative bacilli of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Salmonellae are flagellated, non-lactose-fermenting, and hydrogen sulfide-producing microbes. Salmonella enterica, the most common disease-causing species in humans, is further classified based on serotype as typhoidal (S. typhi and paratyphi) and nontyphoidal (S. enteritidis and typhimurium). Salmonella |

|

| Vibrio vulnificus Vibrio vulnificus A species of halophilic bacteria in the genus vibrio, which lives in warm seawater. It can cause infections in those who eat raw contaminated seafood or have open wounds exposed to seawater. Vibrio |

|

| Clostridium perfringens Clostridium perfringens The most common etiologic agent of gas gangrene. It is differentiable into several distinct types based on the distribution of twelve different toxins. Gas Gangrene |

|

| Escherichia coli Escherichia coli The gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli is a key component of the human gut microbiota. Most strains of E. coli are avirulent, but occasionally they escape the GI tract, infecting the urinary tract and other sites. Less common strains of E. coli are able to cause disease within the GI tract, most commonly presenting as abdominal pain and diarrhea. Escherichia coli |

|

| Shigella Shigella Shigella is a genus of gram-negative, non-lactose-fermenting facultative intracellular bacilli. Infection spreads most commonly via person-to-person contact or through contaminated food and water. Humans are the only known reservoir. Shigella |

|

| Campylobacter Campylobacter Campylobacter (“curved bacteria”) is a genus of thermophilic, S-shaped, gram-negative bacilli. There are many species of Campylobacter, with C. jejuni and C. coli most commonly implicated in human disease. Campylobacter species |

|

|

Chronic watery diarrhea Watery diarrhea Rotavirus in immunosuppressed patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship |

| Giardia Giardia A genus of flagellate intestinal eukaryotes parasitic in various vertebrates, including humans. Characteristics include the presence of four pairs of flagella arising from a complicated system of axonemes and cysts that are ellipsoidal to ovoidal in shape. Nitroimidazoles |

|

| Rotavirus Rotavirus A genus of Reoviridae, causing acute gastroenteritis in birds and mammals, including humans. Transmission is horizontal and by environmental contamination. Seven species (rotaviruses A through G) are recognized. Rotavirus and norovirus Norovirus Norovirus is a nonenveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus belonging to the Caliciviridae family. Norovirus infections are transmitted via the fecal-oral route or by aerosols from vomiting. The virus is one of the most common causes of nonbacterial gastroenteritis epidemic worldwide. Symptoms include watery and nonbloody diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and low-grade fever. Norovirus |

|

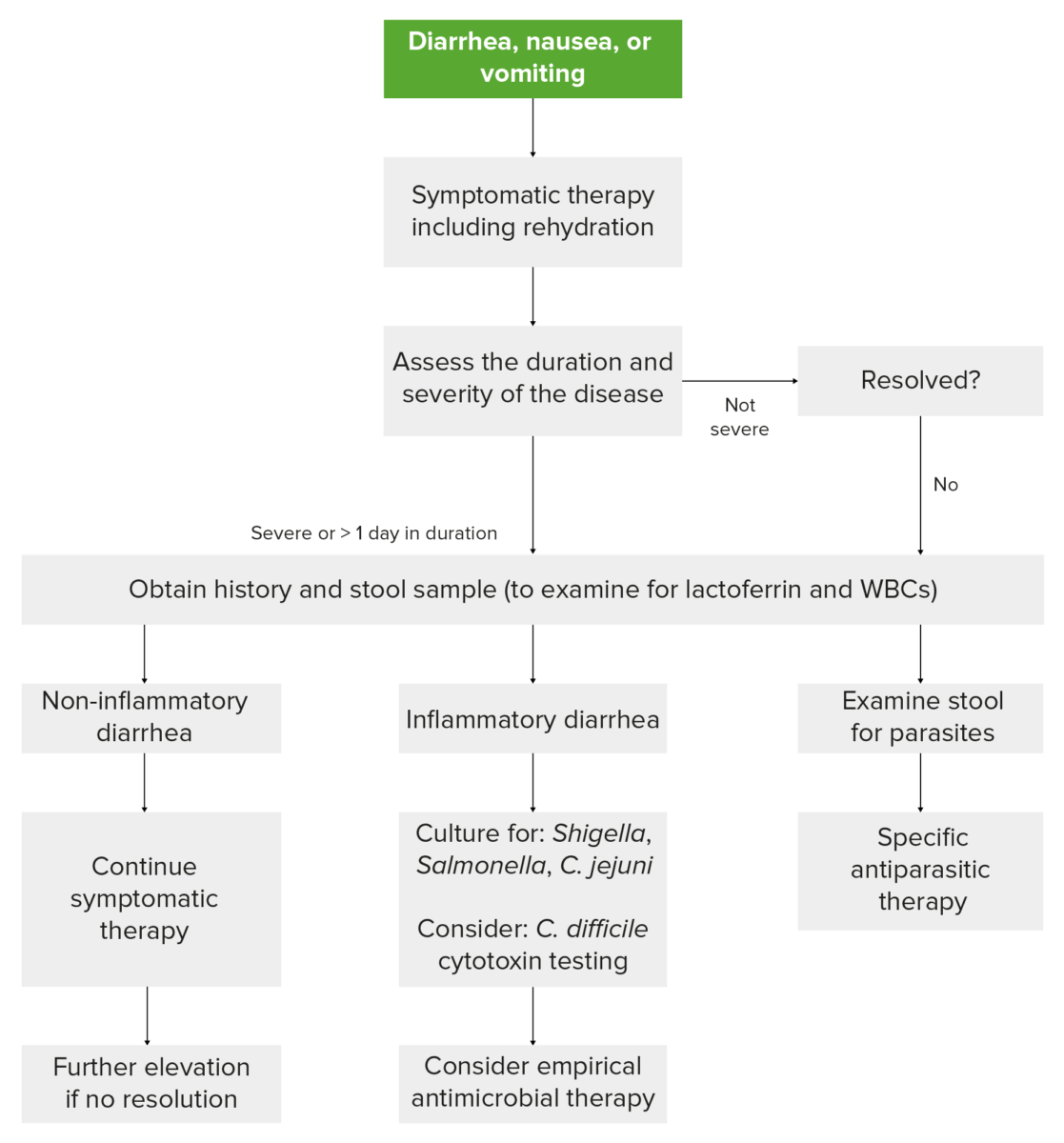

The following algorithm summarizes the workup of gastroenteritis:

Workup of gastroenteritis

Image by Lecturio.| Complication | Description | Organism responsible |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic diarrhea Diarrhea Diarrhea is defined as ≥ 3 watery or loose stools in a 24-hour period. There are a multitude of etiologies, which can be classified based on the underlying mechanism of disease. The duration of symptoms (acute or chronic) and characteristics of the stools (e.g., watery, bloody, steatorrheic, mucoid) can help guide further diagnostic evaluation. Diarrhea (lasting more than 2 weeks) |

|

Can occur with any type of acute diarrhea Diarrhea Diarrhea is defined as ≥ 3 watery or loose stools in a 24-hour period. There are a multitude of etiologies, which can be classified based on the underlying mechanism of disease. The duration of symptoms (acute or chronic) and characteristics of the stools (e.g., watery, bloody, steatorrheic, mucoid) can help guide further diagnostic evaluation. Diarrhea, especially protozoal |

| Initial presentation or exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease | Due to triggering of the inflammatory response | Can occur with any type of acute diarrhea Diarrhea Diarrhea is defined as ≥ 3 watery or loose stools in a 24-hour period. There are a multitude of etiologies, which can be classified based on the underlying mechanism of disease. The duration of symptoms (acute or chronic) and characteristics of the stools (e.g., watery, bloody, steatorrheic, mucoid) can help guide further diagnostic evaluation. Diarrhea, especially C. difficile |

| Reactive arthritis Arthritis Acute or chronic inflammation of joints. Osteoarthritis |

|

|

| HUS HUS Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a clinical phenomenon most commonly seen in children that consists of a classic triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury. Hemolytic uremic syndrome is a major cause of acute kidney injury in children and is most commonly associated with a prodrome of diarrheal illness caused by shiga-like toxin-producing bacteria. Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome |

|

Follows infection with Shiga toxin-producing bacteria Bacteria Bacteria are prokaryotic single-celled microorganisms that are metabolically active and divide by binary fission. Some of these organisms play a significant role in the pathogenesis of diseases. Bacteriology ( Shigella Shigella Shigella is a genus of gram-negative, non-lactose-fermenting facultative intracellular bacilli. Infection spreads most commonly via person-to-person contact or through contaminated food and water. Humans are the only known reservoir. Shigella and enterohemorrhagic E. coli) |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome Guillain-Barré syndrome Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), once thought to be a single disease process, is a family of immune-mediated polyneuropathies that occur after infections (e.g., with Campylobacter jejuni). Guillain-Barré Syndrome | Acute immune-mediated polyneuropathies Polyneuropathies Diseases of multiple peripheral nerves simultaneously. Polyneuropathies usually are characterized by symmetrical, bilateral distal motor and sensory impairment with a graded increase in severity distally. The pathological processes affecting peripheral nerves include degeneration of the axon, myelin or both. The various forms of polyneuropathy are categorized by the type of nerve affected (e.g., sensory, motor, or autonomic), by the distribution of nerve injury (e.g., distal vs. Proximal), by nerve component primarily affected (e.g., demyelinating vs. axonal), by etiology, or by pattern of inheritance. Mononeuropathy and Plexopathy | Campylobacter Campylobacter Campylobacter (“curved bacteria”) is a genus of thermophilic, S-shaped, gram-negative bacilli. There are many species of Campylobacter, with C. jejuni and C. coli most commonly implicated in human disease. Campylobacter |

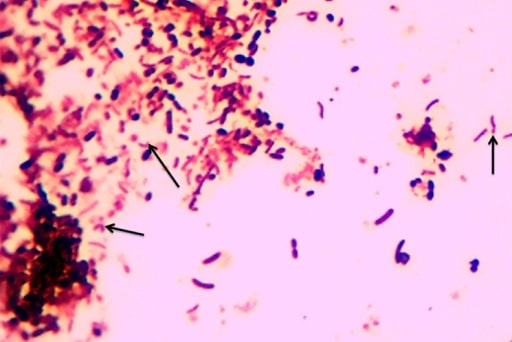

Image showing the characteristic S-shaped or seagull wing-shaped Campylobacter

Image: “F0001” by the Department of Microbiology/Immunology, Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Mwanza, Tanzania. License: CC BY 2.0.Shigella Shigella Shigella is a genus of gram-negative, non-lactose-fermenting facultative intracellular bacilli. Infection spreads most commonly via person-to-person contact or through contaminated food and water. Humans are the only known reservoir. Shigella causes bacillary dysentery, also known as shigellosis Shigellosis Shigella.

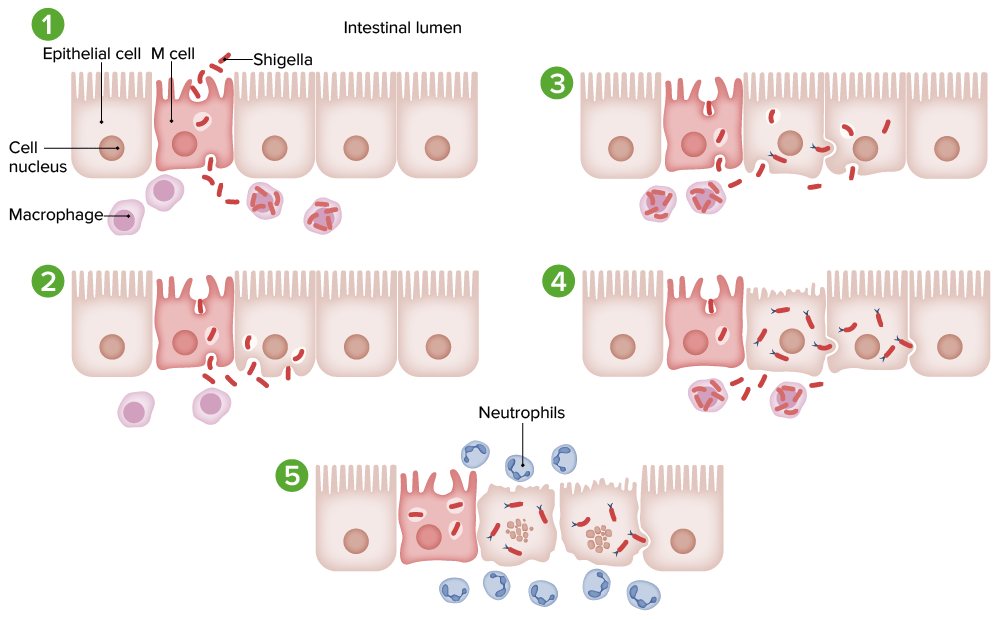

Pathogenesis of Shigella infection:

1. Microfold cells (M cells) are invaded by Shigella through macropinocytosis and taken up by macrophages.

2. The death of macrophages causes release of the bacteria. Epithelial cells are invaded by macrophages, inferiorly and laterally, through endocytosis. Lysis of the endosomes releases the bacteria into the cytoplasm.

3. Polymerized actin filaments enable cell-to-cell spread.

4. Shigella multiplies and spreads infection into the adjacent cell.

5. Death of infected cells triggers an acute inflammatory response (neutrophils), which results in bleeding and abscess formation.

Cholera Cholera An acute diarrheal disease endemic in india and southeast Asia whose causative agent is Vibrio cholerae. This condition can lead to severe dehydration in a matter of hours unless quickly treated. Vibrio is a severe form of gastroenteritis caused by Vibrio cholerae Vibrio cholerae The etiologic agent of cholera. Vibrio (V. cholerae).

The following table briefly summarizes the milder form of gastroenteritis caused by non-cholera Vibrio Vibrio Vibrio is a genus of comma-shaped, gram-negative bacilli. It is halophilic, acid labile, and commonly isolated on thiosulfate-citrate-bile-sucrose (TCBS) agar. There are 3 clinically relevant species: Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae), Vibrio vulnificus (V. vulnificus), and Vibrio parahaemolyticus (V. parahaemolyticus). Vibrio species:

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus Vibrio parahaemolyticus A species of bacteria found in the marine environment, sea foods, and the feces of patients with acute enteritis. Vibrio | Vibrio Vibrio Vibrio is a genus of comma-shaped, gram-negative bacilli. It is halophilic, acid labile, and commonly isolated on thiosulfate-citrate-bile-sucrose (TCBS) agar. There are 3 clinically relevant species: Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae), Vibrio vulnificus (V. vulnificus), and Vibrio parahaemolyticus (V. parahaemolyticus). Vibrio mimicus | Vibrio vulnificus Vibrio vulnificus A species of halophilic bacteria in the genus vibrio, which lives in warm seawater. It can cause infections in those who eat raw contaminated seafood or have open wounds exposed to seawater. Vibrio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distinguishing feature |

|

|

|

| Transmission | Consumption of undercooked or raw seafood | Consumption of undercooked or raw seafood |

|

| Disease | Gastroenteritis | Gastroenteritis |

|

| Clinical presentation | Watery diarrhea Watery diarrhea Rotavirus with cramping and abdominal pain Abdominal Pain Acute Abdomen | Watery diarrhea Watery diarrhea Rotavirus, nausea Nausea An unpleasant sensation in the stomach usually accompanied by the urge to vomit. Common causes are early pregnancy, sea and motion sickness, emotional stress, intense pain, food poisoning, and various enteroviruses. Antiemetics, abdominal cramping Abdominal cramping Norovirus |

|

| Management | Self-limiting Self-Limiting Meningitis in Children | Self-limiting Self-Limiting Meningitis in Children |

|

Clostridium perfringens Clostridium perfringens The most common etiologic agent of gas gangrene. It is differentiable into several distinct types based on the distribution of twelve different toxins. Gas Gangrene enterocolitis Enterocolitis Inflammation of the mucosa of both the small intestine and the large intestine. Etiology includes ischemia, infections, allergic, and immune responses. Yersinia spp./Yersiniosis will be discussed here.

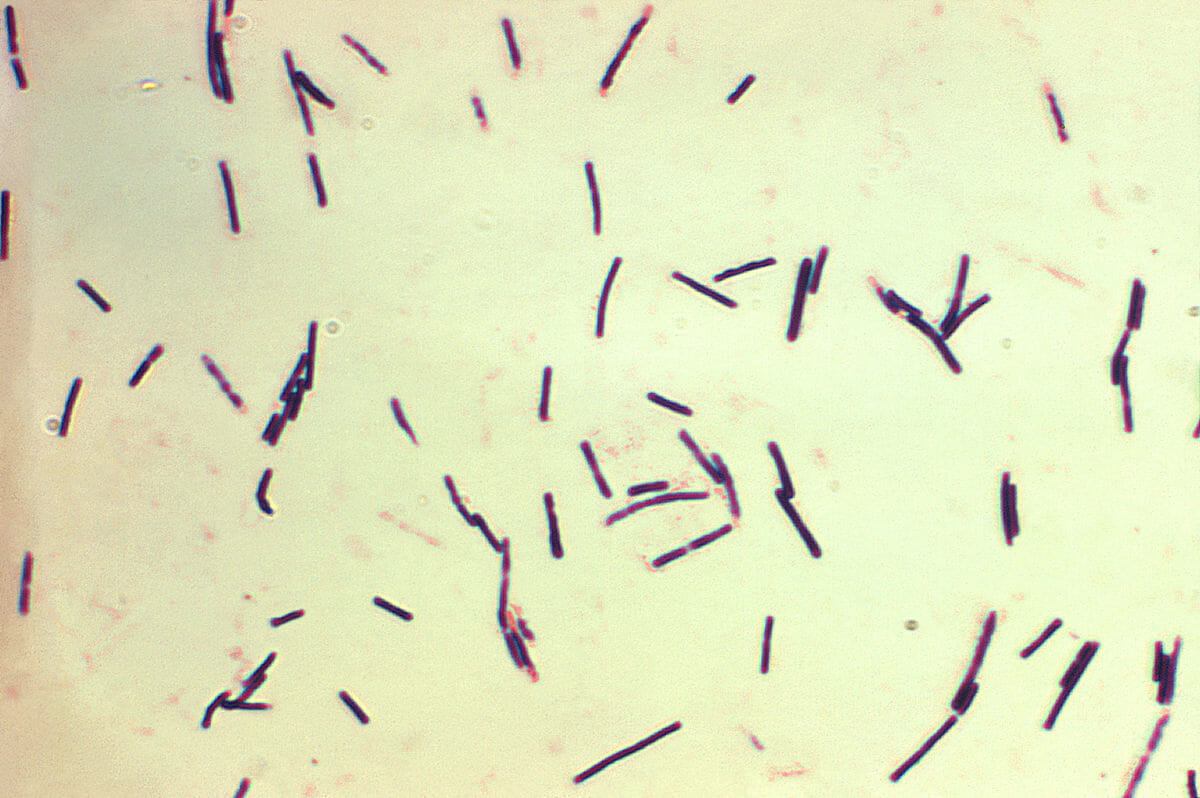

Photomicrograph of gram-positive Clostridium perfringens bacilli

Image: “Clostridium perfringens” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Don Stalons. License: Public Domain

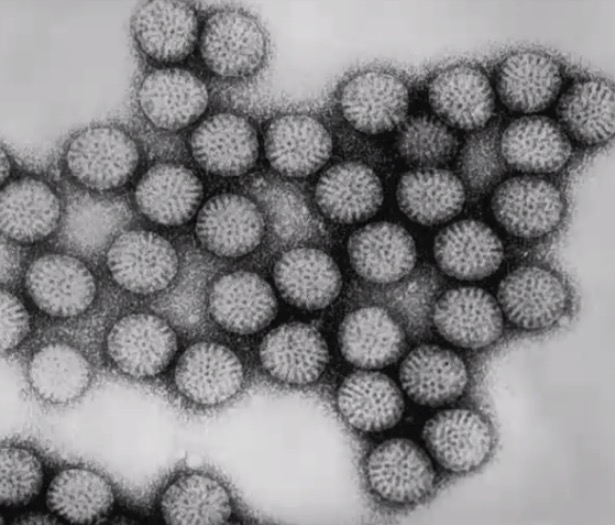

Transmission electron micrograph of rotavirus particles

Image by CDC/Dr. Erskine Palmer, PD.

Electron microscopy of norovirus

Image: “Norovirus” by Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Marine Science, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, 4 -5-7, Konan, Minato-ku, Tokyo, 108-8477 Japan. License: CC BY 4.0, edited by Lecturio

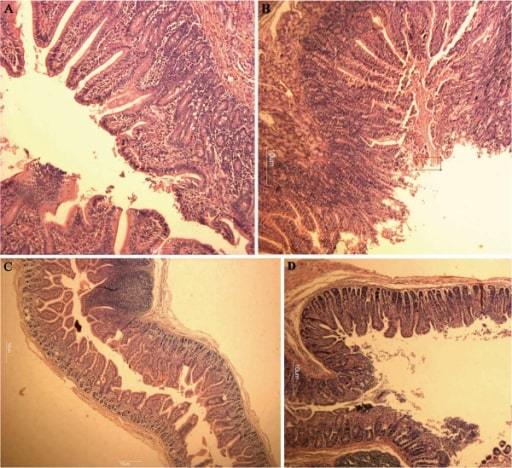

Hematoxylin and eosin stain:

A: Normal-appearing, long villi of the duodenum

B: Villi of the duodenum showing mild villous atrophy from a norovirus infection

C: Normal-appearing, long villi of the jejunum

D: Villi of the jejunum showing mild villous atrophy from a norovirus infection