Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium Bacillus Bacillus Bacillus are aerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive bacilli. Two pathogenic species are Bacillus anthracis (B. anthracis) and B. cereus. Bacillus anthracis, which usually targets the skin Skin The skin, also referred to as the integumentary system, is the largest organ of the body. The skin is primarily composed of the epidermis (outer layer) and dermis (deep layer). The epidermis is primarily composed of keratinocytes that undergo rapid turnover, while the dermis contains dense layers of connective tissue. Skin: Structure and Functions, lungs Lungs Lungs are the main organs of the respiratory system. Lungs are paired viscera located in the thoracic cavity and are composed of spongy tissue. The primary function of the lungs is to oxygenate blood and eliminate CO2. Lungs: Anatomy, or intestines. Anthrax is a zoonotic disease and is usually transmitted to humans from animals Animals Unicellular or multicellular, heterotrophic organisms, that have sensation and the power of voluntary movement. Under the older five kingdom paradigm, animalia was one of the kingdoms. Under the modern three domain model, animalia represents one of the many groups in the domain eukaryota. Cell Types: Eukaryotic versus Prokaryotic or through animal products. The Bacillus Bacillus Bacillus are aerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive bacilli. Two pathogenic species are Bacillus anthracis (B. anthracis) and B. cereus. Bacillus spores can persist in soil for a long time. The Bacillus Bacillus Bacillus are aerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive bacilli. Two pathogenic species are Bacillus anthracis (B. anthracis) and B. cereus. Bacillus spores have also been used as a biological weapon. Symptoms depend on which organ system is affected. The skin Skin The skin, also referred to as the integumentary system, is the largest organ of the body. The skin is primarily composed of the epidermis (outer layer) and dermis (deep layer). The epidermis is primarily composed of keratinocytes that undergo rapid turnover, while the dermis contains dense layers of connective tissue. Skin: Structure and Functions forms small blisters with surrounding swelling Swelling Inflammation that often turn into a painless ulcer with a black center. Inhalational exposure causes severe fulminant pneumonia Pneumonia Pneumonia or pulmonary inflammation is an acute or chronic inflammation of lung tissue. Causes include infection with bacteria, viruses, or fungi. In more rare cases, pneumonia can also be caused through toxic triggers through inhalation of toxic substances, immunological processes, or in the course of radiotherapy. Pneumonia. Intestinal exposure causes mucosal ulcers, bloody diarrhea Bloody diarrhea Diarrhea, abdominal pain Abdominal Pain Acute Abdomen, nausea Nausea An unpleasant sensation in the stomach usually accompanied by the urge to vomit. Common causes are early pregnancy, sea and motion sickness, emotional stress, intense pain, food poisoning, and various enteroviruses. Antiemetics, and vomiting Vomiting The forcible expulsion of the contents of the stomach through the mouth. Hypokalemia. Diagnosis is established with cultures, tissue examination, and polymerase chain reaction Polymerase chain reaction Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a technique that amplifies DNA fragments exponentially for analysis. The process is highly specific, allowing for the targeting of specific genomic sequences, even with minuscule sample amounts. The PCR cycles multiple times through 3 phases: denaturation of the template DNA, annealing of a specific primer to the individual DNA strands, and synthesis/elongation of new DNA molecules. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) ( PCR PCR Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a technique that amplifies DNA fragments exponentially for analysis. The process is highly specific, allowing for the targeting of specific genomic sequences, even with minuscule sample amounts. The PCR cycles multiple times through 3 phases: denaturation of the template DNA, annealing of a specific primer to the individual DNA strands, and synthesis/elongation of new DNA molecules. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)). Management involves antibiotics, antitoxins, and frequently hospital/critical care admission. Mortality Mortality All deaths reported in a given population. Measures of Health Status from systemic disease remains high.

Last updated: Apr 14, 2025

Anthrax is an infectious disease caused by Bacillus Bacillus Bacillus are aerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive bacilli. Two pathogenic species are Bacillus anthracis (B. anthracis) and B. cereus. Bacillus anthracis ( B. anthracis B. anthracis A species of bacteria that causes anthrax in humans and animals. Bacillus) and can have cutaneous, respiratory, and gastrointestinal manifestations.

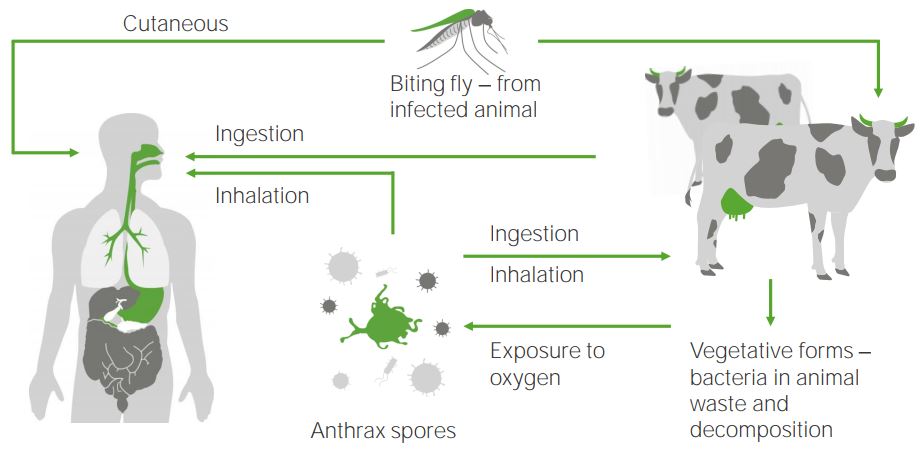

The anthrax cycle:

Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) spores infect humans or mammals via different processes: either via ingestion, inhalation, or through cutaneous pathways by bites from an infected insect. Anthrax spores originate from vegetation in excreted waste from cattle that is exposed to oxygen.

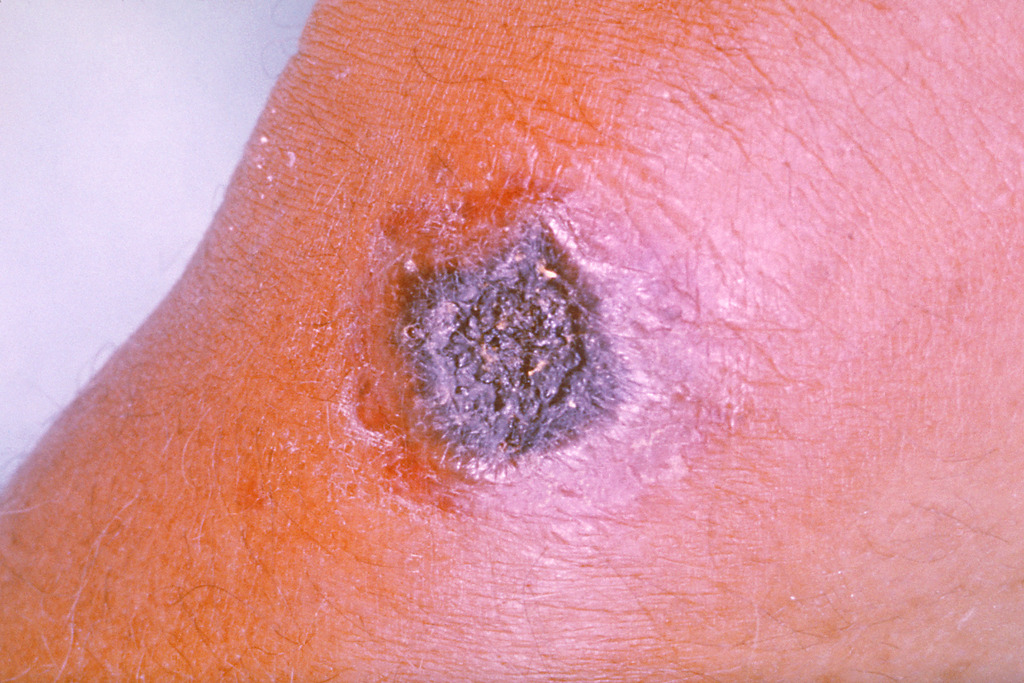

Cutaneous anthrax Cutaneous anthrax Bacillus:

Anthrax skin infection

Image: “Anthrax” by the CDC/James H. Steele. License: Public Domain

Cutaneous anthrax

Image: “Skin reaction to anthrax” by United States Army. License: Public DomainGastrointestinal anthrax Gastrointestinal anthrax Bacillus:

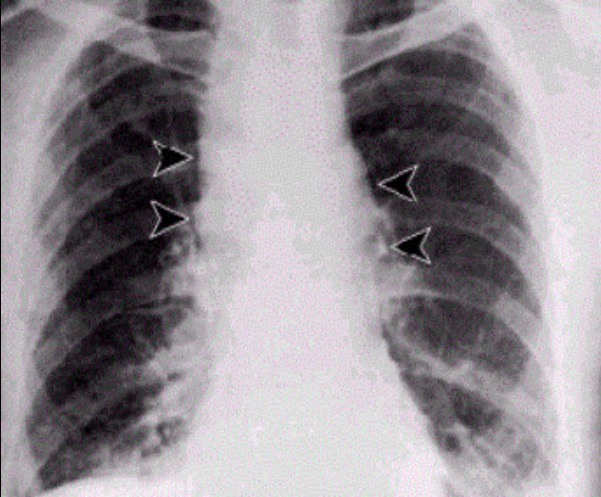

Inhalation anthrax (“woolsorter’s disease”):

Injection anthrax:

Pulmonary anthrax: Chest X-ray shows mediastinal widening.

Image: “Inhalational anthrax” by JoJan. License: Public Domain

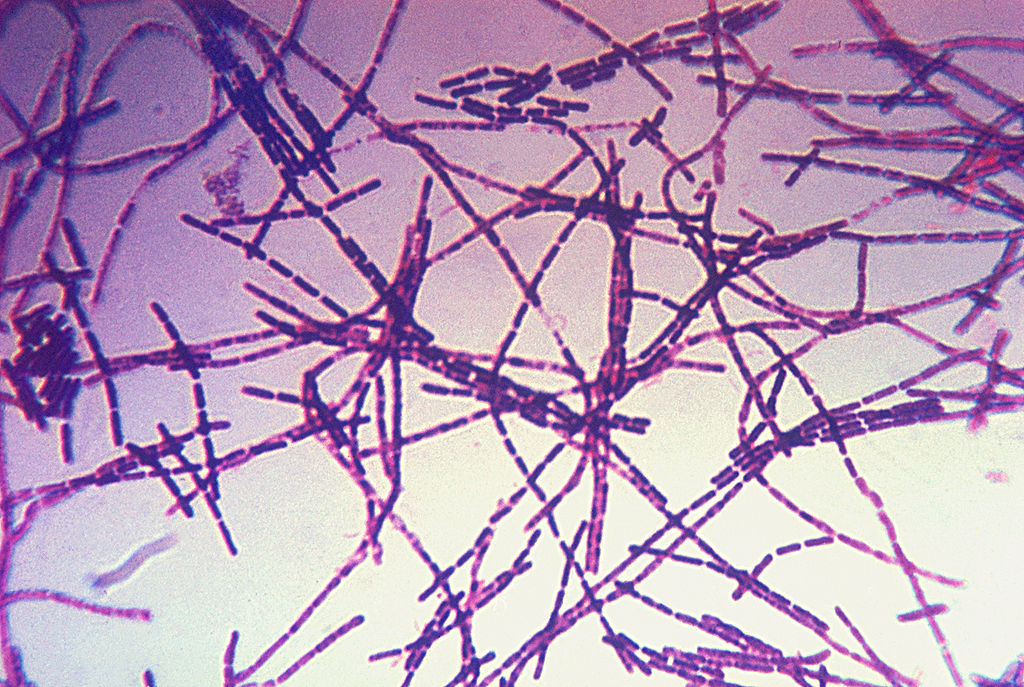

Gram stain of B. anthracis

Image: “Photomicrograph of a Gram stain of the bacterium Bacillus anthracis” by CDC. License: Public DomainCutaneous anthrax Cutaneous anthrax Bacillus:

Inhalation anthrax:

Gastrointestinal anthrax Gastrointestinal anthrax Bacillus: