Bordetella is a genus of obligate aerobic, Gram-negative coccobacilli. They are highly fastidious and difficult to isolate. The most important pathologic species is Bordetella pertussis Pertussis Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a potentially life-threatening highly contagious bacterial infection of the respiratory tract caused by Bordetella pertussis. The disease has 3 clinical stages, the second and third of which are characterized by an intense paroxysmal cough, an inspiratory whoop, and post-tussive vomiting. Pertussis (Whooping Cough) (B. pertussis Pertussis Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a potentially life-threatening highly contagious bacterial infection of the respiratory tract caused by Bordetella pertussis. The disease has 3 clinical stages, the second and third of which are characterized by an intense paroxysmal cough, an inspiratory whoop, and post-tussive vomiting. Pertussis (Whooping Cough)), which is commonly isolated on Bordet-Gengou agar. Bordetella pertussis Pertussis Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a potentially life-threatening highly contagious bacterial infection of the respiratory tract caused by Bordetella pertussis. The disease has 3 clinical stages, the second and third of which are characterized by an intense paroxysmal cough, an inspiratory whoop, and post-tussive vomiting. Pertussis (Whooping Cough) is highly infectious via respiratory droplets Droplets Varicella-Zoster Virus/Chickenpox and is only known to infect humans, causing the clinical syndrome of pertussis Pertussis Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a potentially life-threatening highly contagious bacterial infection of the respiratory tract caused by Bordetella pertussis. The disease has 3 clinical stages, the second and third of which are characterized by an intense paroxysmal cough, an inspiratory whoop, and post-tussive vomiting. Pertussis (Whooping Cough). Pertussis Pertussis Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a potentially life-threatening highly contagious bacterial infection of the respiratory tract caused by Bordetella pertussis. The disease has 3 clinical stages, the second and third of which are characterized by an intense paroxysmal cough, an inspiratory whoop, and post-tussive vomiting. Pertussis (Whooping Cough) is characterized by 3 distinct phases: catarral, paroxysmal, and convalescent. Pertussis Pertussis Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a potentially life-threatening highly contagious bacterial infection of the respiratory tract caused by Bordetella pertussis. The disease has 3 clinical stages, the second and third of which are characterized by an intense paroxysmal cough, an inspiratory whoop, and post-tussive vomiting. Pertussis (Whooping Cough) is rare in developed countries due to widespread use of the diphtheria Diphtheria Diphtheria is an infectious disease caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae that most often results in respiratory disease with membranous inflammation of the pharynx, sore throat, fever, swollen glands, and weakness. The hallmark sign is a sheet of thick, gray material covering the back of the throat. Diphtheria, tetanus Tetanus Tetanus is a bacterial infection caused by Clostridium tetani, a gram-positive obligate anaerobic bacterium commonly found in soil that enters the body through a contaminated wound. C. tetani produces a neurotoxin that blocks the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters and causes prolonged tonic muscle contractions. Tetanus, and acellular pertussis Pertussis Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a potentially life-threatening highly contagious bacterial infection of the respiratory tract caused by Bordetella pertussis. The disease has 3 clinical stages, the second and third of which are characterized by an intense paroxysmal cough, an inspiratory whoop, and post-tussive vomiting. Pertussis (Whooping Cough) (DTaP) combined vaccine Vaccine Suspensions of killed or attenuated microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa), antigenic proteins, synthetic constructs, or other bio-molecular derivatives, administered for the prevention, amelioration, or treatment of infectious and other diseases. Vaccination.

Last updated: Jan 9, 2025

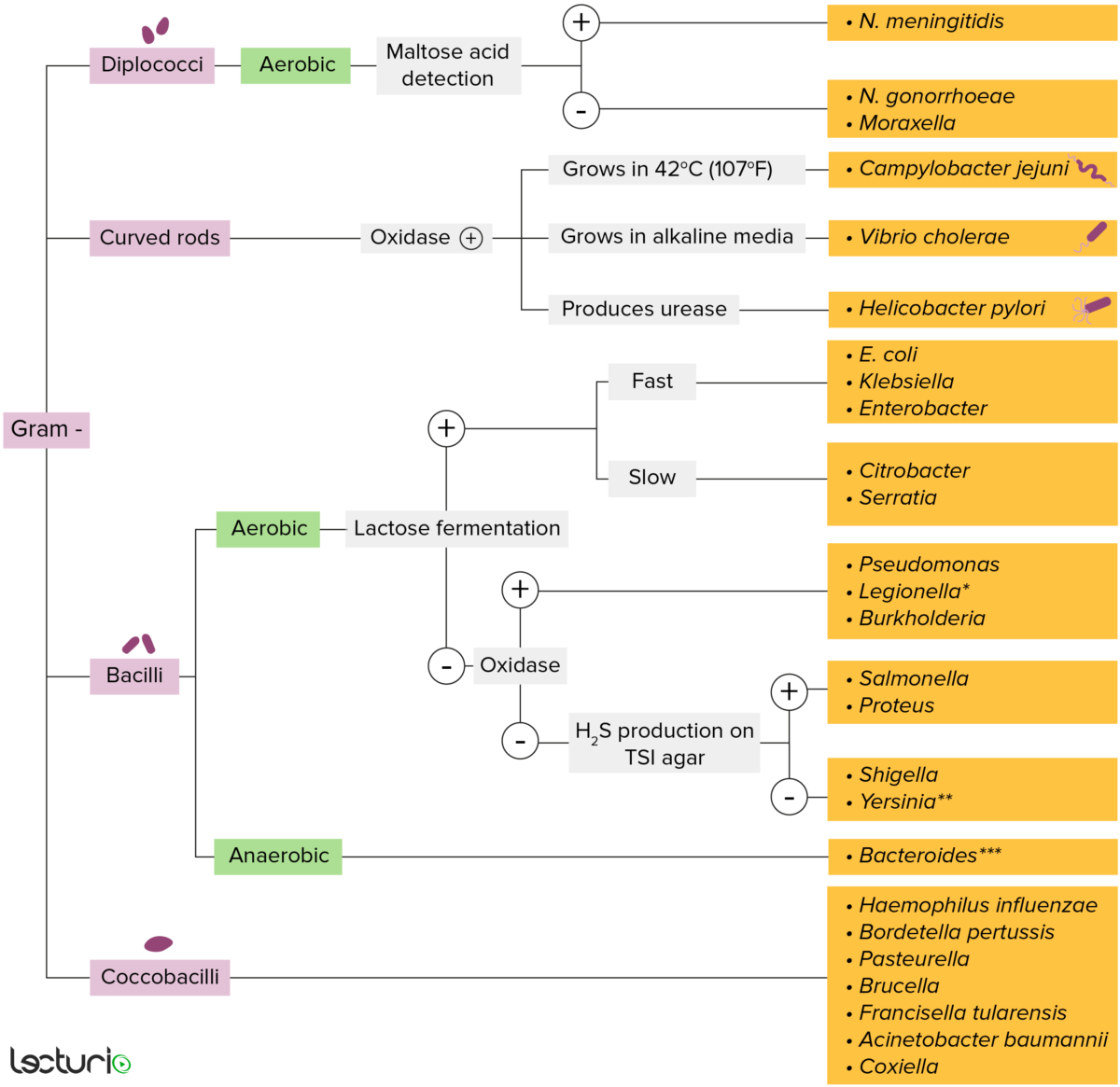

Gram-negative bacteria:

Most bacteria can be classified according to a lab procedure called Gram staining.

Bacteria with cell walls that have a thin layer of peptidoglycan do not retain the crystal violet stain utilized in Gram staining. These bacteria do, however, retain the safranin counterstain and thus appear as pinkish-red on the stain, making them gram negative. These bacteria can be further classified according to morphology (diplococci, curved rods, bacilli, and coccobacilli) and their ability to grow in the presence of oxygen (aerobic versus anaerobic). The bacteria can be more narrowly identified by growing them on specific media (triple sugar iron (TSI) agar) where their enzymes can be identified (urease, oxidase) and their ability to ferment lactose can be tested.

* Stains poorly on Gram stain

** Pleomorphic rod/coccobacillus

*** Require special transport media

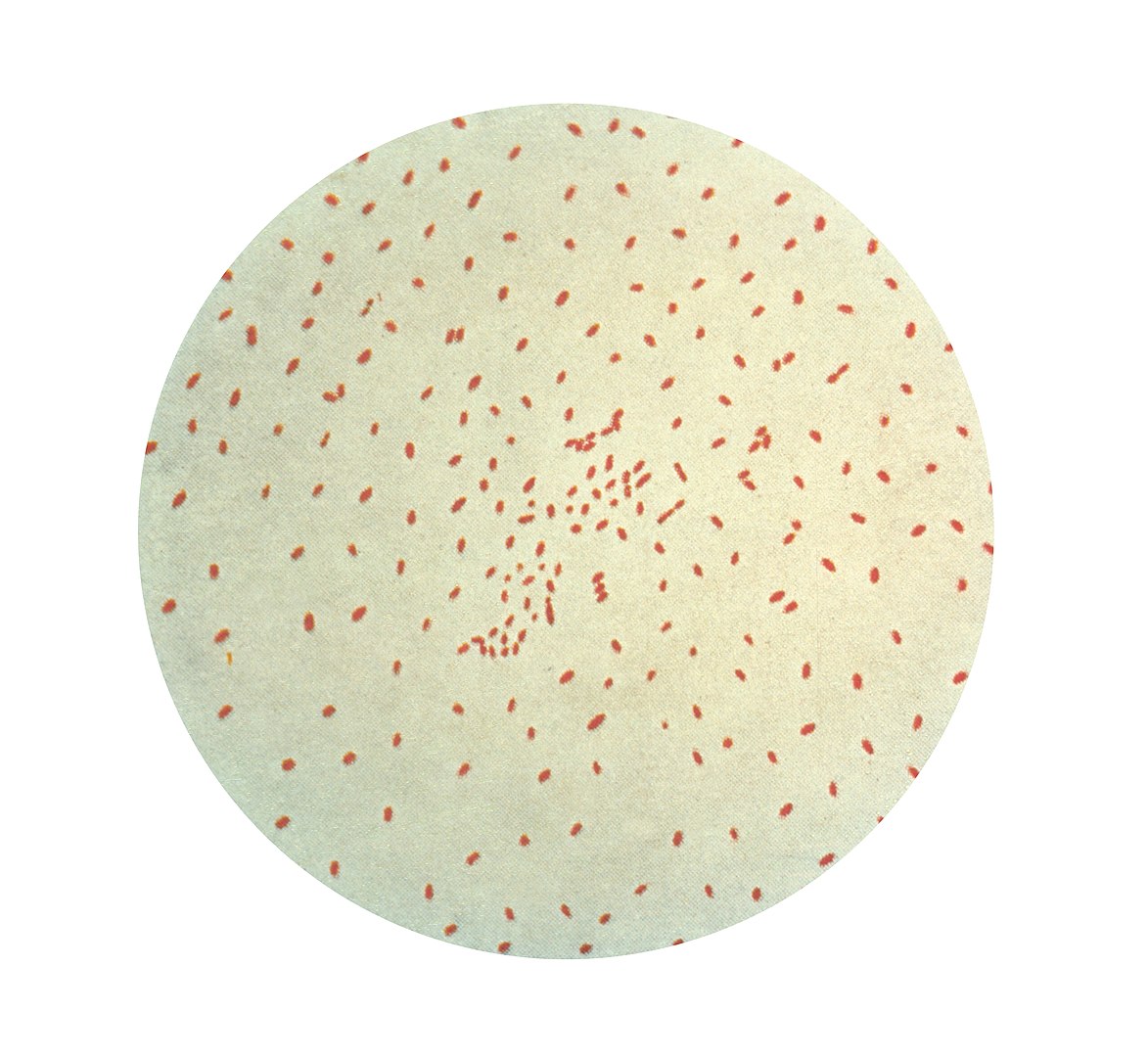

Gram stain of B. pertussis

Image: “Gram stain of Bordetella pertussis” by the CDC Public Health Image Library. License: Public domain.

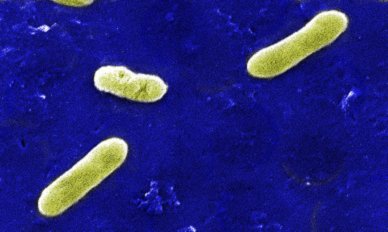

Scanning electron micrograph of Bordetella bronchiseptica

Image: “File:Bordetella bronchiseptica” by the CDC/ Janice Carr. License: Public domain.Pathogenesis:

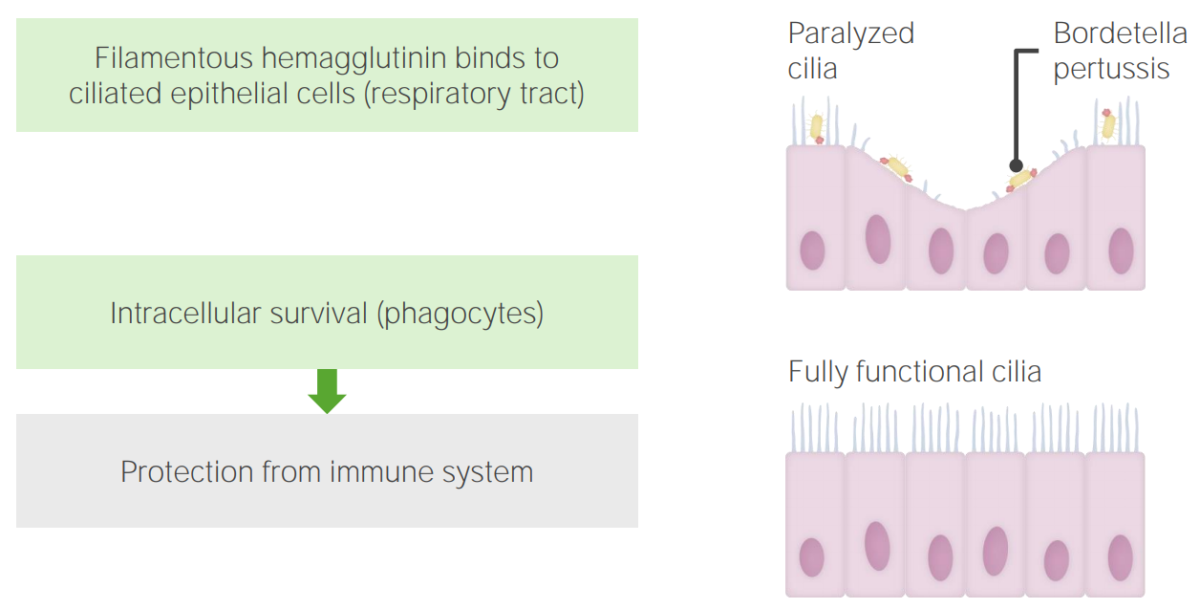

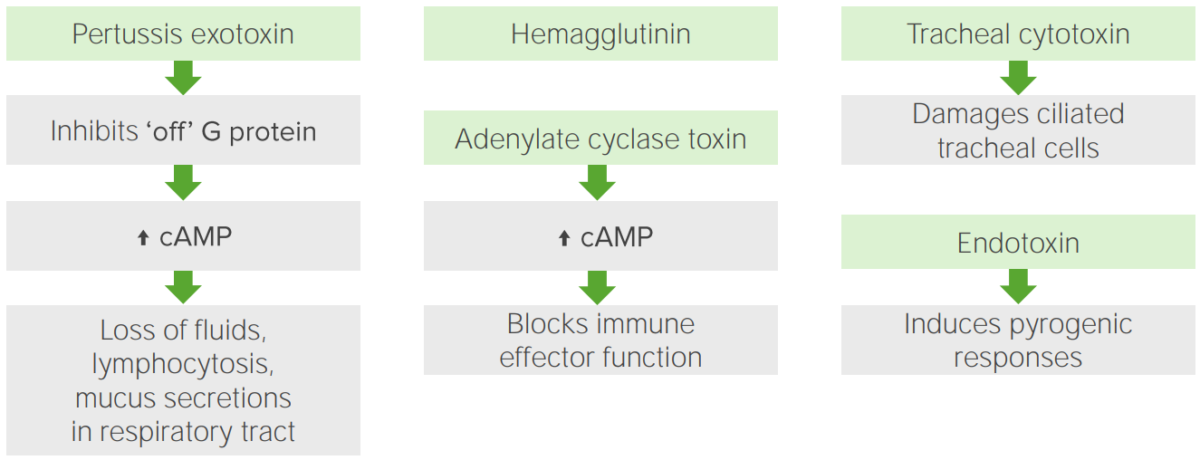

Virulence factors Virulence factors Those components of an organism that determine its capacity to cause disease but are not required for its viability per se. Two classes have been characterized: toxins, biological and surface adhesion molecules that affect the ability of the microorganism to invade and colonize a host. Haemophilus:

Pathogenesis of Bordetella pertussis: Filamentous hemagglutinin binds to the ciliated epithelial cells, poisoning the cells, inhibiting the mucociliary elevation. Another mechanism is the prevention of intracellular digestion by phagocytosis, thereby evading the immune system.

Image by Lecturio.

Pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying the virulence and pathogenic factors

Image by Lecturio.

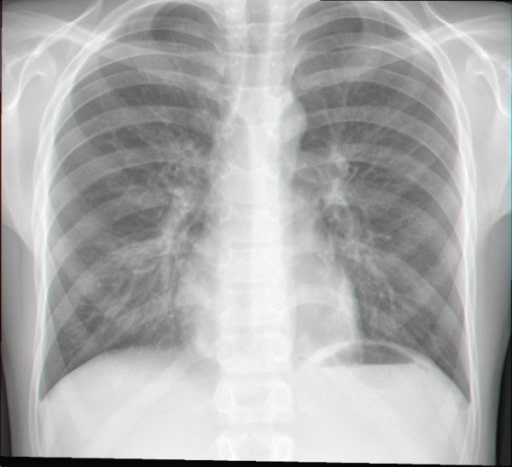

Chest radiograph of an 11-year-old patient with Bordetella pertussis infection Reinforcement of the perihilar bronchovascular reticulum and heterogeneous infiltrates on the inferior third of both lung fields.

Image: “Bordetella pertussis an agent not to forget: a case report.” by Melo N, Dias AC, Isidoro L, Duarte R. License: CC BY 2.0Specimen collection:

Tests: