Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune, inflammatory condition that causes immune-complex deposition in organs, resulting in systemic manifestations. Women, particularly those of African American descent, are more commonly affected. The clinical presentation can vary greatly. Notable clinical features include malar rash Rash Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, nondestructive arthritis Arthritis Acute or chronic inflammation of joints. Osteoarthritis, lupus nephritis Lupus nephritis Glomerulonephritis associated with autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus nephritis is histologically classified into 6 classes: class I - normal glomeruli, class II - pure mesangial alterations, class III - focal segmental glomerulonephritis, class IV - diffuse glomerulonephritis, class V - diffuse membranous glomerulonephritis, and class VI - advanced sclerosing glomerulonephritis (the world health organization classification 1982). Diffuse Proliferative Glomerulonephritis, serositis, cytopenia, thromboembolic disease, seizures Seizures A seizure is abnormal electrical activity of the neurons in the cerebral cortex that can manifest in numerous ways depending on the region of the brain affected. Seizures consist of a sudden imbalance that occurs between the excitatory and inhibitory signals in cortical neurons, creating a net excitation. The 2 major classes of seizures are focal and generalized. Seizures, and/or psychosis. Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria, and includes tests to determine ANAs, SLE-specific antibodies Antibodies Immunoglobulins (Igs), also known as antibodies, are glycoprotein molecules produced by plasma cells that act in immune responses by recognizing and binding particular antigens. The various Ig classes are IgG (the most abundant), IgM, IgE, IgD, and IgA, which differ in their biologic features, structure, target specificity, and distribution. Immunoglobulins: Types and Functions, and specific clinical findings. The goal of management is to control symptoms and prevent organ damage, using corticosteroids Corticosteroids Chorioretinitis, hydroxychloroquine Hydroxychloroquine A chemotherapeutic agent that acts against erythrocytic forms of malarial parasites. Hydroxychloroquine appears to concentrate in food vacuoles of affected protozoa. It inhibits plasmodial heme polymerase. Immunosuppressants, and immunosuppressants Immunosuppressants Immunosuppressants are a class of drugs widely used in the management of autoimmune conditions and organ transplant rejection. The general effect is dampening of the immune response. Immunosuppressants.

Last updated: May 16, 2024

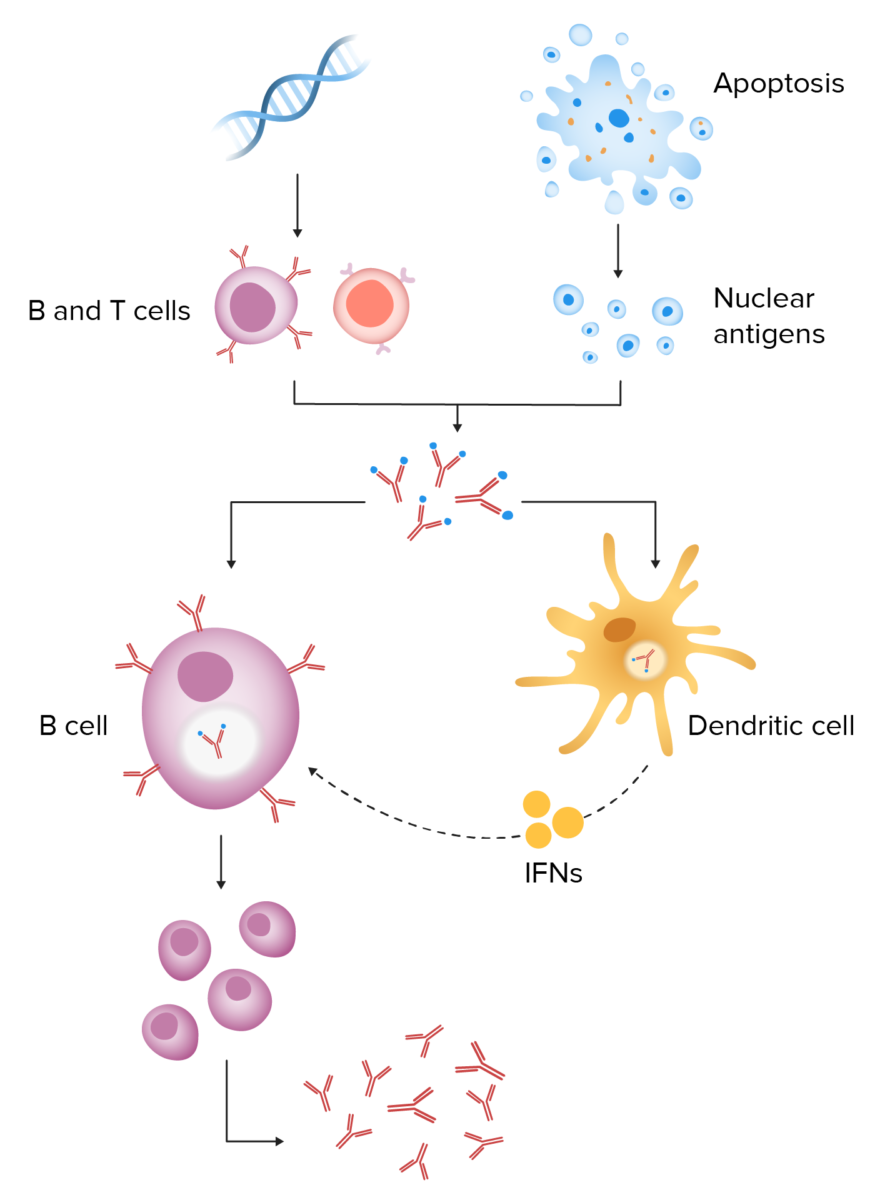

The exact mechanism is unknown. Patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship likely have a genetic predisposition to autoreactive immune cells (B and T cells T cells Lymphocytes responsible for cell-mediated immunity. Two types have been identified – cytotoxic (t-lymphocytes, cytotoxic) and helper T-lymphocytes (t-lymphocytes, helper-inducer). They are formed when lymphocytes circulate through the thymus gland and differentiate to thymocytes. When exposed to an antigen, they divide rapidly and produce large numbers of new T cells sensitized to that antigen. T cells: Types and Functions).

Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus:

Genetic predisposition results in autoreactive B and T cells. When an environmental trigger causes cell apoptosis, defective clearance of cellular debris results in increased exposure to nuclear antigens. These antigens and autoantibodies lead to immune-complex formation. Endocytosis of the immune complexes results in interferon release from dendritic cells, leading to continuous activation of B cells and persistent antibody production.

The clinical presentation of SLE is highly variable Variable Variables represent information about something that can change. The design of the measurement scales, or of the methods for obtaining information, will determine the data gathered and the characteristics of that data. As a result, a variable can be qualitative or quantitative, and may be further classified into subgroups. Types of Variables and can include several organ systems.

Photosensitive lesions on the hand of a patient with SLE

Image: “Photosensitive lesions” by Faculdade de Medicina de Lisboa, Clinica Universitária de Dermatologia, Avenido Prof. Egas Moniz, 1649-035 Lisboa, Portugal. License: CC BY 3.0

Malar rash of SLE: typical “butterfly” rash that spares the nasolabial folds

Image: “Malar rash” by Faculdade de Medicina de Lisboa, Clinica Universitária de Dermatologia, Avenido Prof. Egas Moniz, 1649-035 Lisboa, Portugal. License: CC BY 3.0

Typical malar rash in a patient with SLE: Notice the sparing of the nasolabial folds.

Image: “Typical features” by Department of Bacteriology and Immunology, Haartman Institute, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. License: CC BY 4.0

Discoid rash in a patient with SLE

Image: “Discoid rash on patient’s neck and chest” by Wards 45 and 46 A, National Hospital of Sri Lanka, Regent Street, Colombo, Sri Lanka. License: CC BY 2.0

Cutaneous presentation of discoid lupus:

Image shows scaling plaque and scarring.

Cutaneous presentation of neonatal lupus:

Rash shows annular lesions with raised borders.

Cutaneous presentation of neonatal lupus:

Periorbital, scaly, erythematous lesions are seen.

When SLE is initially suspected: ANA

If ANA is positive, the following should be evaluated:

| Domain | Criteria | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical findings | ||

| Constitutional | Fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever | 2 |

| Mucocutaneous | Non-scarring alopecia Non-Scarring Alopecia Alopecia | 2 |

| Oral ulcers Oral ulcers A loss of mucous substance of the mouth showing local excavation of the surface, resulting from the sloughing of inflammatory necrotic tissue. It is the result of a variety of causes, e.g., denture irritation, aphthous stomatitis; necrotizing gingivitis, toothbrushing, and various irritants. Chédiak-Higashi Syndrome | 2 | |

| Subacute cutaneous or discoid lupus | 4 | |

| Acute cutaneous lupus | 6 | |

| Musculoskeletal | > 2 joints involved | 6 |

| Neuropsychiatric | Delirium Delirium Delirium is a medical condition characterized by acute disturbances in attention and awareness. Symptoms may fluctuate during the course of a day and involve memory deficits and disorientation. Delirium | 2 |

| Psychosis | 3 | |

| Seizure | 5 | |

| Serositis | Pleural or pericardial effusion Pericardial effusion Fluid accumulation within the pericardium. Serous effusions are associated with pericardial diseases. Hemopericardium is associated with trauma. Lipid-containing effusion (chylopericardium) results from leakage of thoracic duct. Severe cases can lead to cardiac tamponade. Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Tamponade | 5 |

| Acute pericarditis Acute pericarditis Pericarditis | 6 | |

| Hematological | Leukopenia | 3 |

| Thrombocytopenia Thrombocytopenia Thrombocytopenia occurs when the platelet count is < 150,000 per microliter. The normal range for platelets is usually 150,000-450,000/µL of whole blood. Thrombocytopenia can be a result of decreased production, increased destruction, or splenic sequestration of platelets. Patients are often asymptomatic until platelet counts are < 50,000/µL. Thrombocytopenia | 4 | |

| Autoimmune hemolysis | 4 | |

| Renal | Proteinuria Proteinuria The presence of proteins in the urine, an indicator of kidney diseases. Nephrotic Syndrome in Children | 4 |

| Renal biopsy Renal Biopsy Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA)-Associated Vasculitis class II or V lupus nephritis Lupus nephritis Glomerulonephritis associated with autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus nephritis is histologically classified into 6 classes: class I – normal glomeruli, class II – pure mesangial alterations, class III – focal segmental glomerulonephritis, class IV – diffuse glomerulonephritis, class V – diffuse membranous glomerulonephritis, and class VI – advanced sclerosing glomerulonephritis (the world health organization classification 1982). Diffuse Proliferative Glomerulonephritis | 8 | |

| Renal biopsy Renal Biopsy Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA)-Associated Vasculitis class III or IV lupus nephritis Lupus nephritis Glomerulonephritis associated with autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus nephritis is histologically classified into 6 classes: class I – normal glomeruli, class II – pure mesangial alterations, class III – focal segmental glomerulonephritis, class IV – diffuse glomerulonephritis, class V – diffuse membranous glomerulonephritis, and class VI – advanced sclerosing glomerulonephritis (the world health organization classification 1982). Diffuse Proliferative Glomerulonephritis | 10 | |

| Immunological findings | ||

| SLE-specific antibodies Antibodies Immunoglobulins (Igs), also known as antibodies, are glycoprotein molecules produced by plasma cells that act in immune responses by recognizing and binding particular antigens. The various Ig classes are IgG (the most abundant), IgM, IgE, IgD, and IgA, which differ in their biologic features, structure, target specificity, and distribution. Immunoglobulins: Types and Functions | Anti-dsDNA antibody or anti-Smith antibody | 6 |

| Complement levels | Low C3 or C4 | 3 |

| Low C3 and C4 | 4 | |

| Antiphospholipid antibodies Antiphospholipid antibodies Autoantibodies directed against phospholipids. These antibodies are characteristically found in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome; related autoimmune diseases, some non-autoimmune diseases, and also in healthy individuals. Antiphospholipid Syndrome | Anti-cardiolipin antibody or lupus anticoagulant Lupus anticoagulant An antiphospholipid antibody found in association with systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome; and in a variety of other diseases as well as in healthy individuals. In vitro, the antibody interferes with the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin and prolongs the partial thromboplastin time. In vivo, it exerts a procoagulant effect resulting in thrombosis mainly in the larger veins and arteries. It further causes obstetrical complications, including fetal death and spontaneous abortion, as well as a variety of hematologic and neurologic complications. Antiphospholipid Syndrome or anti-beta2-glycoprotein antibody | 2 |

To help recall some criteria, remember “SOAP BRAIN MD:”

As there is no definitive treatment available, management is aimed at controlling acute flares, suppressing symptoms, and preventing organ damage.

To recall the 3 most common causes of death in SLE, remember: “Lupus patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship die with Redness In their Cheeks.”