Pneumoconiosis is an occupational disease that results from the inhalation and deposition of mineral dusts and other inorganic particles in the lung. It can be categorized according to the type of causative particle involved or by the type of response provoked. Coal, silica, asbestos, and talc are the classic fibrogenic types, while beryllium provokes a granulomatous response, and cobalt is associated with giant cell pneumonia Giant cell pneumonia Measles Virus. Iron Iron A metallic element with atomic symbol fe, atomic number 26, and atomic weight 55. 85. It is an essential constituent of hemoglobins; cytochromes; and iron-binding proteins. It plays a role in cellular redox reactions and in the transport of oxygen. Trace Elements, tin, and barium are considered benign Benign Fibroadenoma or inert particle types because they do not cause the same type of reactions as the others. After exposure to the fibrogenic types of particles, macrophages Macrophages The relatively long-lived phagocytic cell of mammalian tissues that are derived from blood monocytes. Main types are peritoneal macrophages; alveolar macrophages; histiocytes; kupffer cells of the liver; and osteoclasts. They may further differentiate within chronic inflammatory lesions to epithelioid cells or may fuse to form foreign body giant cells or langhans giant cells. Innate Immunity: Phagocytes and Antigen Presentation and fibroblasts Fibroblasts Connective tissue cells which secrete an extracellular matrix rich in collagen and other macromolecules. Sarcoidosis become activated within the pulmonary parenchyma leading to chronic inflammation Chronic Inflammation Inflammation and fibrosis Fibrosis Any pathological condition where fibrous connective tissue invades any organ, usually as a consequence of inflammation or other injury. Bronchiolitis Obliterans, which can progress to respiratory failure Respiratory failure Respiratory failure is a syndrome that develops when the respiratory system is unable to maintain oxygenation and/or ventilation. Respiratory failure may be acute or chronic and is classified as hypoxemic, hypercapnic, or a combination of the two. Respiratory Failure and death. Occupational history and chest X-rays X-rays X-rays are high-energy particles of electromagnetic radiation used in the medical field for the generation of anatomical images. X-rays are projected through the body of a patient and onto a film, and this technique is called conventional or projectional radiography. X-rays are the mainstays of diagnosis and staging Staging Methods which attempt to express in replicable terms the extent of the neoplasm in the patient. Grading, Staging, and Metastasis. Management is mainly symptomatic.

Last updated: May 17, 2024

Pneumoconiosis is the classic term used to describe the non-neoplastic lung reaction to chronic inhalation of mineral dusts encountered at the workplace. Some lung experts believe that the term “pneumoconiosis” should also include diseases induced by chemical fumes and vapors but this is not a widespread practice and will not be followed here.

Most common causes:

Less common causes, not discussed further in this monograph:

Fiber-specific pathogenesis:

Factors of disease progression:

Onset depends on the intensity and duration of exposure and of the type of dust inhaled.

A diagnosis of occupational lung disease relies upon 4 essential criteria:

| Silicosis | Asbestosis | CWP | Berylliosis |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Most cases of pneumoconiosis show a restrictive lung disease pattern by spirometry Spirometry Measurement of volume of air inhaled or exhaled by the lung. Pulmonary Function Tests.

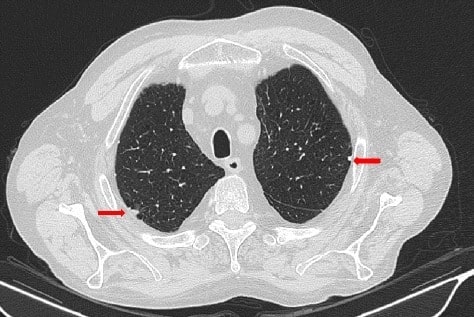

Thoracic high resonance CT scan of a patient with asbestosis reveals pleural plaques (arrows)

Image: “Thoracic HRCT” by Consultant in Rheumatology, Rheumatology Division, Hospital of Prato, Prato, Italy. License: CC BY 4.0

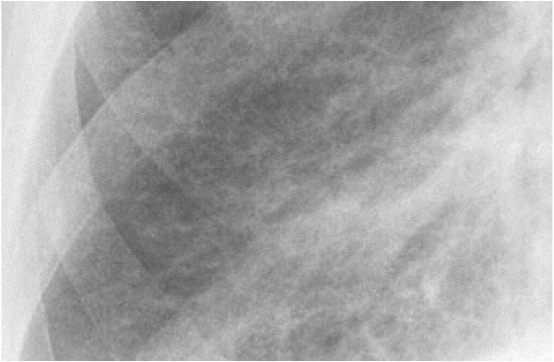

Close up of a chest X-ray of a patient with asbestosis which shows signs of interstitial fibrosis

Image: “Asbestosis” by DrSHaber. License: CC0 1.0

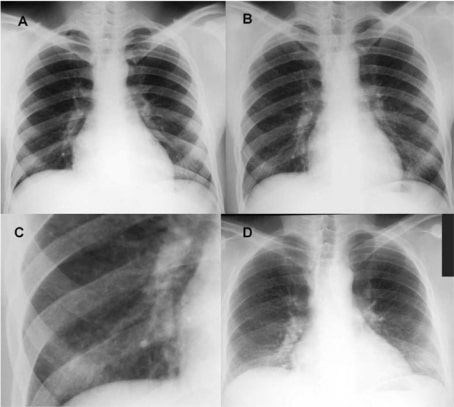

Chest X-ray of a patient with progressive pneumoconiosis (silicosis) with signs of massive fibrosis

Image: “Chest X-ray” by Department of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, College of Medicine, Dong-A University, Busan, Korea. License: CC BY 2.0, edited by Lecturio.

Chest X-ray of a patient with berylliosis due to occupational exposure

(A) Taken pre-hire in March 1979, showing normal lung fields

(B) Taken during the second episode of acute work-related illness in March 1981, showing a mild diffuse nodular infiltrate

(C) Close-up of the right lower lung field from image B

(D) Taken at follow-up in February 1997, showing reduced lung volumes and bilateral interstitial infiltrates

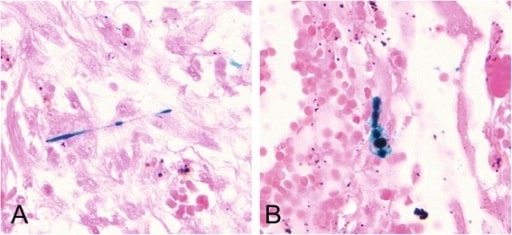

Histologic slide shows scattered asbestos bodies showing a fibrous core coated by iron-containing material. Prussian blue staining (400×).

Image: “Scattered asbestos bodies showing a fibrous core” by Institute and Outpatient Clinic for Occupational and Social Medicine, University Medical Center Giessen, Aulweg 129/III, D-35385 Giessen, Germany. License: CC BY 4.0The differential diagnoses of pneumoconioses caused by mineral dusts include the following conditions: