Crohn's disease is a chronic, recurrent condition that causes patchy transmural inflammation Inflammation Inflammation is a complex set of responses to infection and injury involving leukocytes as the principal cellular mediators in the body's defense against pathogenic organisms. Inflammation is also seen as a response to tissue injury in the process of wound healing. The 5 cardinal signs of inflammation are pain, heat, redness, swelling, and loss of function. Inflammation that can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract. It is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) along with ulcerative colitis Colitis Inflammation of the colon section of the large intestine, usually with symptoms such as diarrhea (often with blood and mucus), abdominal pain, and fever. Pseudomembranous Colitis ( UC UC Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic inflammatory condition that involves the mucosal surface of the colon. It is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), along with Crohn's disease (CD). The rectum is always involved, and inflammation may extend proximally through the colon. Ulcerative Colitis). The terminal ileum Ileum The distal and narrowest portion of the small intestine, between the jejunum and the ileocecal valve of the large intestine. Small Intestine: Anatomy and proximal colon Colon The large intestines constitute the last portion of the digestive system. The large intestine consists of the cecum, appendix, colon (with ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid segments), rectum, and anal canal. The primary function of the colon is to remove water and compact the stool prior to expulsion from the body via the rectum and anal canal. Colon, Cecum, and Appendix: Anatomy are usually affected. Crohn's disease typically presents with intermittent, non-bloody diarrhea Diarrhea Diarrhea is defined as ≥ 3 watery or loose stools in a 24-hour period. There are a multitude of etiologies, which can be classified based on the underlying mechanism of disease. The duration of symptoms (acute or chronic) and characteristics of the stools (e.g., watery, bloody, steatorrheic, mucoid) can help guide further diagnostic evaluation. Diarrhea and crampy abdominal pain Abdominal Pain Acute Abdomen. Extraintestinal manifestations may include calcium Calcium A basic element found in nearly all tissues. It is a member of the alkaline earth family of metals with the atomic symbol ca, atomic number 20, and atomic weight 40. Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the body and combines with phosphorus to form calcium phosphate in the bones and teeth. It is essential for the normal functioning of nerves and muscles and plays a role in blood coagulation (as factor IV) and in many enzymatic processes. Electrolytes oxalate renal stones, gallstones Gallstones Cholelithiasis (gallstones) is the presence of stones in the gallbladder. Most gallstones are cholesterol stones, while the rest are composed of bilirubin (pigment stones) and other mixed components. Patients are commonly asymptomatic but may present with biliary colic (intermittent pain in the right upper quadrant). Cholelithiasis, erythema Erythema Redness of the skin produced by congestion of the capillaries. This condition may result from a variety of disease processes. Chalazion nodosum, and arthritis Arthritis Acute or chronic inflammation of joints. Osteoarthritis. Diagnosis is established via endoscopy Endoscopy Procedures of applying endoscopes for disease diagnosis and treatment. Endoscopy involves passing an optical instrument through a small incision in the skin i.e., percutaneous; or through a natural orifice and along natural body pathways such as the digestive tract; and/or through an incision in the wall of a tubular structure or organ, i.e. Transluminal, to examine or perform surgery on the interior parts of the body. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) with biopsy Biopsy Removal and pathologic examination of specimens from the living body. Ewing Sarcoma that shows transmural inflammation Inflammation Inflammation is a complex set of responses to infection and injury involving leukocytes as the principal cellular mediators in the body's defense against pathogenic organisms. Inflammation is also seen as a response to tissue injury in the process of wound healing. The 5 cardinal signs of inflammation are pain, heat, redness, swelling, and loss of function. Inflammation, characteristic “cobblestone” mucosa, and noncaseating granulomas Granulomas A relatively small nodular inflammatory lesion containing grouped mononuclear phagocytes, caused by infectious and noninfectious agents. Sarcoidosis. Management is with corticosteroids Corticosteroids Chorioretinitis, azathioprine Azathioprine An immunosuppressive agent used in combination with cyclophosphamide and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. According to the fourth annual report on carcinogens, this substance has been listed as a known carcinogen. Immunosuppressants, antibiotics, and anti-TNF agents ( infliximab Infliximab A chimeric monoclonal antibody to tnf-alpha that is used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis; ankylosing spondylitis; psoriatic arthritis and Crohn's disease. Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) and adalimumab Adalimumab A humanized monoclonal antibody that binds specifically to tnf-alpha and blocks its interaction with endogenous tnf receptors to modulate inflammation. It is used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis; psoriatic arthritis; Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs)). Complications include malabsorption Malabsorption General term for a group of malnutrition syndromes caused by failure of normal intestinal absorption of nutrients. Malabsorption and Maldigestion, malnutrition Malnutrition Malnutrition is a clinical state caused by an imbalance or deficiency of calories and/or micronutrients and macronutrients. The 2 main manifestations of acute severe malnutrition are marasmus (total caloric insufficiency) and kwashiorkor (protein malnutrition with characteristic edema). Malnutrition in children in resource-limited countries, intestinal obstruction Intestinal obstruction Any impairment, arrest, or reversal of the normal flow of intestinal contents toward the anal canal. Ascaris/Ascariasis or fistula Fistula Abnormal communication most commonly seen between two internal organs, or between an internal organ and the surface of the body. Anal Fistula, and an increased risk of colon Colon The large intestines constitute the last portion of the digestive system. The large intestine consists of the cecum, appendix, colon (with ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid segments), rectum, and anal canal. The primary function of the colon is to remove water and compact the stool prior to expulsion from the body via the rectum and anal canal. Colon, Cecum, and Appendix: Anatomy cancer.

Last updated: Mar 24, 2025

The exact pathophysiology is unknown but likely associated with a combination of dysregulation of the intestinal epithelium Epithelium The epithelium is a complex of specialized cellular organizations arranged into sheets and lining cavities and covering the surfaces of the body. The cells exhibit polarity, having an apical and a basal pole. Structures important for the epithelial integrity and function involve the basement membrane, the semipermeable sheet on which the cells rest, and interdigitations, as well as cellular junctions. Surface Epithelium: Histology and the immune system Immune system The body’s defense mechanism against foreign organisms or substances and deviant native cells. It includes the humoral immune response and the cell-mediated response and consists of a complex of interrelated cellular, molecular, and genetic components. Primary Lymphatic Organs.

Location and pattern of inflammation Inflammation Inflammation is a complex set of responses to infection and injury involving leukocytes as the principal cellular mediators in the body’s defense against pathogenic organisms. Inflammation is also seen as a response to tissue injury in the process of wound healing. The 5 cardinal signs of inflammation are pain, heat, redness, swelling, and loss of function. Inflammation:

The typical presentation of Crohn’s disease is a relapsing disorder that includes:

Reactivation Reactivation Herpes Simplex Virus 1 and 2 of CD in an asymptomatic period can be triggered by physical or psychological stress Psychological stress Stress wherein emotional factors predominate. Acute Stress Disorder, sudden or drastic changes in diet, and smoking Smoking Willful or deliberate act of inhaling and exhaling smoke from burning substances or agents held by hand. Interstitial Lung Diseases.

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Image: “Vegetating idiopathic pyoderma gangrenosum” by Service de Dermatologie, CHU Ibn Sina, Rabat, Maroc. License: CC BY 2.0The diagnosis of Crohn’s disease should be suspected if a patient presents with the above-noted symptoms of abdominal pain Abdominal Pain Acute Abdomen, chronic intermittent diarrhea Diarrhea Diarrhea is defined as ≥ 3 watery or loose stools in a 24-hour period. There are a multitude of etiologies, which can be classified based on the underlying mechanism of disease. The duration of symptoms (acute or chronic) and characteristics of the stools (e.g., watery, bloody, steatorrheic, mucoid) can help guide further diagnostic evaluation. Diarrhea, fatigue Fatigue The state of weariness following a period of exertion, mental or physical, characterized by a decreased capacity for work and reduced efficiency to respond to stimuli. Fibromyalgia, and weight loss Weight loss Decrease in existing body weight. Bariatric Surgery. The initial workup includes the following:

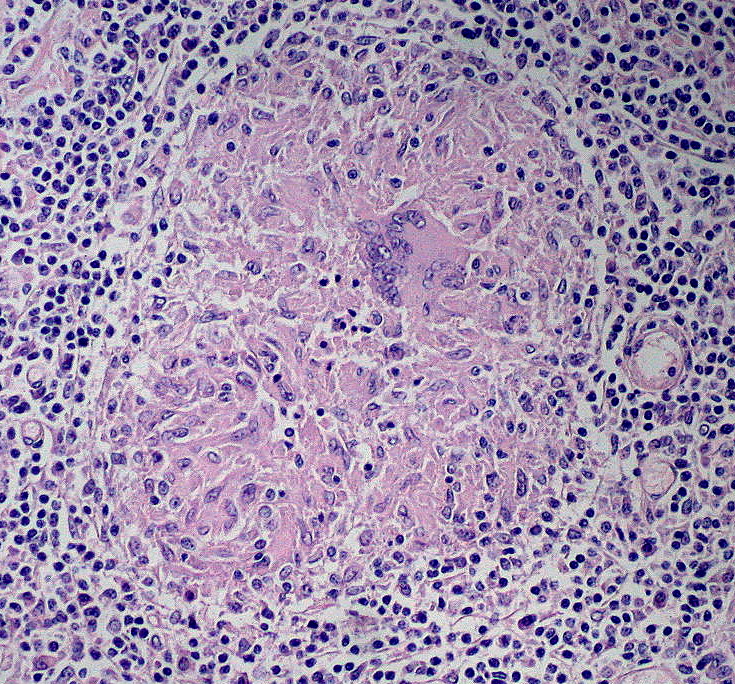

Non-caseating granuloma

Image: “Noncaseating Granuloma” by Ed Uthman. License: CC BY 2.0

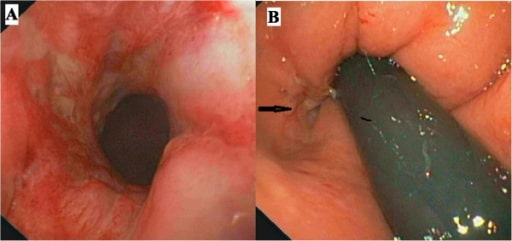

Colonoscopy. Panel A shows the rectal inflamed mucosa and panel B (arrow) the opening of an anal fistula.

Image: “ Colonoscopy” by Gastroenterology Unit, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Salerno, Baronissi Campus, via S, Allende, 84081 Baronissi, Salerno, Italy. License: CC BY 4.0

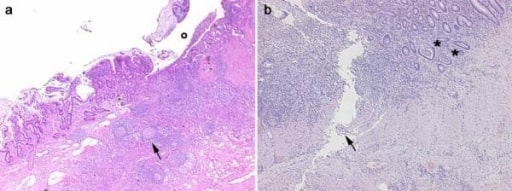

Histological images obtained from 2 IBD patients. Panel a, CD: in the transmural section is clearly evident an ulceration (o) in the mucosa and submucosa with diffuse inflammatory infiltrations, pseudo-follicle nodules (arrow), and fibrosis of the intestinal wall. Panel b, UC: the inflammatory infiltration is more evident in the mucosa and submucosa with crypt abscesses (asterisks). A serpiginous linear ulcer is evident (arrow).

Image: “Histological images obtained from two IBD patients enrolled in the study affected by CD” by Department of Surgery, Ospedale Maggiore di Milano, IRCCS, University of Milan, V. F. Sforza, 35 – 20122, Milan, Italy. License: CC BY 2.0

(A) Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) shows irregular wall thickening, separation of ileal loops (white short arrow), colon wall thickening, and luminal stenosis (white long arrow);

(B) MRI shows wall thickening of the distal ileum (white short arrows) and descending colon (white long arrows) with significant enhancement;

(C) Conventional gastrointestinal radiography (CGR) shows stenosis of the distal ileum (white short arrows) and descending colon (white long arrows), edema, and broadening of fat space around the intestine;

(D) Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) shows ulcerations (white short arrow) and polypoid lesions (white long arrow) in the ileum.

Dilated ileal loop with irregular wall thickening (white arrow in the RLQ) and descending colon wall thickening and luminal stenosis (white arrow in green circle in the LLQ).

Image: “MRE, CGR and VCE correlation” by Departments of Radiology, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310000, P.R. China. License: CC BY 3.0, edited by Lecturio.Medical therapies for Crohn’s disease depend on the severity of the disease. The 2 main therapeutic goals are to terminate an acute, symptomatic attack and to prevent recurrent attacks.

In general, management consists of the following:

The following conditions are differential diagnoses of Crohn’s disease:

| Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis Colitis Inflammation of the colon section of the large intestine, usually with symptoms such as diarrhea (often with blood and mucus), abdominal pain, and fever. Pseudomembranous Colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern of involvement | Skip lesions in any part of the GI tract:

|

Continuous lesions:

|

| GI symptoms | Usually non-bloody diarrhea Diarrhea Diarrhea is defined as ≥ 3 watery or loose stools in a 24-hour period. There are a multitude of etiologies, which can be classified based on the underlying mechanism of disease. The duration of symptoms (acute or chronic) and characteristics of the stools (e.g., watery, bloody, steatorrheic, mucoid) can help guide further diagnostic evaluation. Diarrhea, may be bloody at times |

Bloody diarrhea

Bloody diarrhea

Diarrhea

|

| Extraintestinal manifestations | Cholelithiasis Cholelithiasis Cholelithiasis (gallstones) is the presence of stones in the gallbladder. Most gallstones are cholesterol stones, while the rest are composed of bilirubin (pigment stones) and other mixed components. Patients are commonly asymptomatic but may present with biliary colic (intermittent pain in the right upper quadrant). Cholelithiasis and nephrolithiasis Nephrolithiasis Nephrolithiasis is the formation of a stone, or calculus, anywhere along the urinary tract caused by precipitations of solutes in the urine. The most common type of kidney stone is the calcium oxalate stone, but other types include calcium phosphate, struvite (ammonium magnesium phosphate), uric acid, and cystine stones. Nephrolithiasis with calcium Calcium A basic element found in nearly all tissues. It is a member of the alkaline earth family of metals with the atomic symbol ca, atomic number 20, and atomic weight 40. Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the body and combines with phosphorus to form calcium phosphate in the bones and teeth. It is essential for the normal functioning of nerves and muscles and plays a role in blood coagulation (as factor IV) and in many enzymatic processes. Electrolytes oxalate stones | Primary sclerosing cholangitis Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is an inflammatory disease that causes fibrosis and strictures of the bile ducts. The exact etiology is unknown, but there is a strong association with IBD. Patients typically present with an insidious onset of fatigue, pruritus, and jaundice, which can progress to cirrhosis and complications related to biliary obstruction. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis |

|

||

| Complications |

|

|

|

||

| Macroscopic findings | Transmural

inflammation

Inflammation

Inflammation is a complex set of responses to infection and injury involving leukocytes as the principal cellular mediators in the body’s defense against pathogenic organisms. Inflammation is also seen as a response to tissue injury in the process of wound healing. The 5 cardinal signs of inflammation are pain, heat, redness, swelling, and loss of function.

Inflammation

|

Mucosal and submucosal

inflammation

Inflammation

Inflammation is a complex set of responses to infection and injury involving leukocytes as the principal cellular mediators in the body’s defense against pathogenic organisms. Inflammation is also seen as a response to tissue injury in the process of wound healing. The 5 cardinal signs of inflammation are pain, heat, redness, swelling, and loss of function.

Inflammation

|

| Microscopic findings |

|

|

| Treatment |

|

|