Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the 2nd-leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Almost all cases of CRC are adenocarcinoma and the majority of lesions come from the malignant transformation of an adenomatous polyp. As most CRCs are asymptomatic, screening is essential in detecting early disease. Screening is recommended to start at the age of 45 years, utilizing various screening tools available with colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and fecal tests among them. For high-risk individuals, earlier and more frequent screening Screening Preoperative Care is recommended. Other stool-based strategies and visualization tests are also available for CRC screening Screening Preoperative Care.

Last updated: Apr 28, 2025

Polyp of sigmoid colon revealed by colonoscopy: The polyp is pedunculated (with a short stalk).

Image: “Colon polyp” by Dr. F.C. Turner. License: CC BY 2.5Colorectal cancer Colorectal cancer Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the 2nd leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. Colorectal cancer is a heterogeneous disease that arises from genetic and epigenetic abnormalities, with influence from environmental factors. Colorectal Cancer is generally a preventable cancer when proper screening Screening Preoperative Care is performed. Screening Screening Preoperative Care:

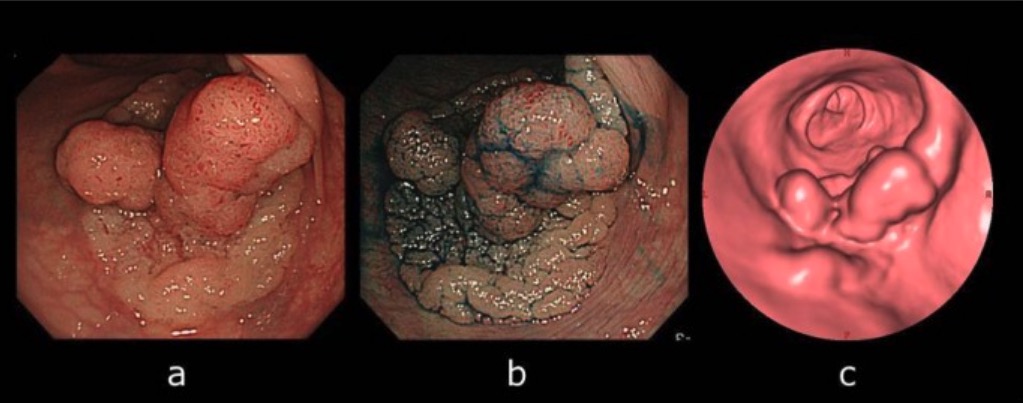

Colon cancer found on colonoscopy confirmed via biopsy

Image: “Primary tumor” by Second Department of Surgery, Wakayama Medical University, School of Medicine, 811-1 Kimiidera, Wakayama 641-8510, Japan. License: CC BY 2.0

Computed tomographic colonography (CTC) and colonoscopy:

A: Colonoscopy view of the lesion

B: Lesion became apparent by indigo-carmine spraying.

C: CTC showing laterally spreading lesion

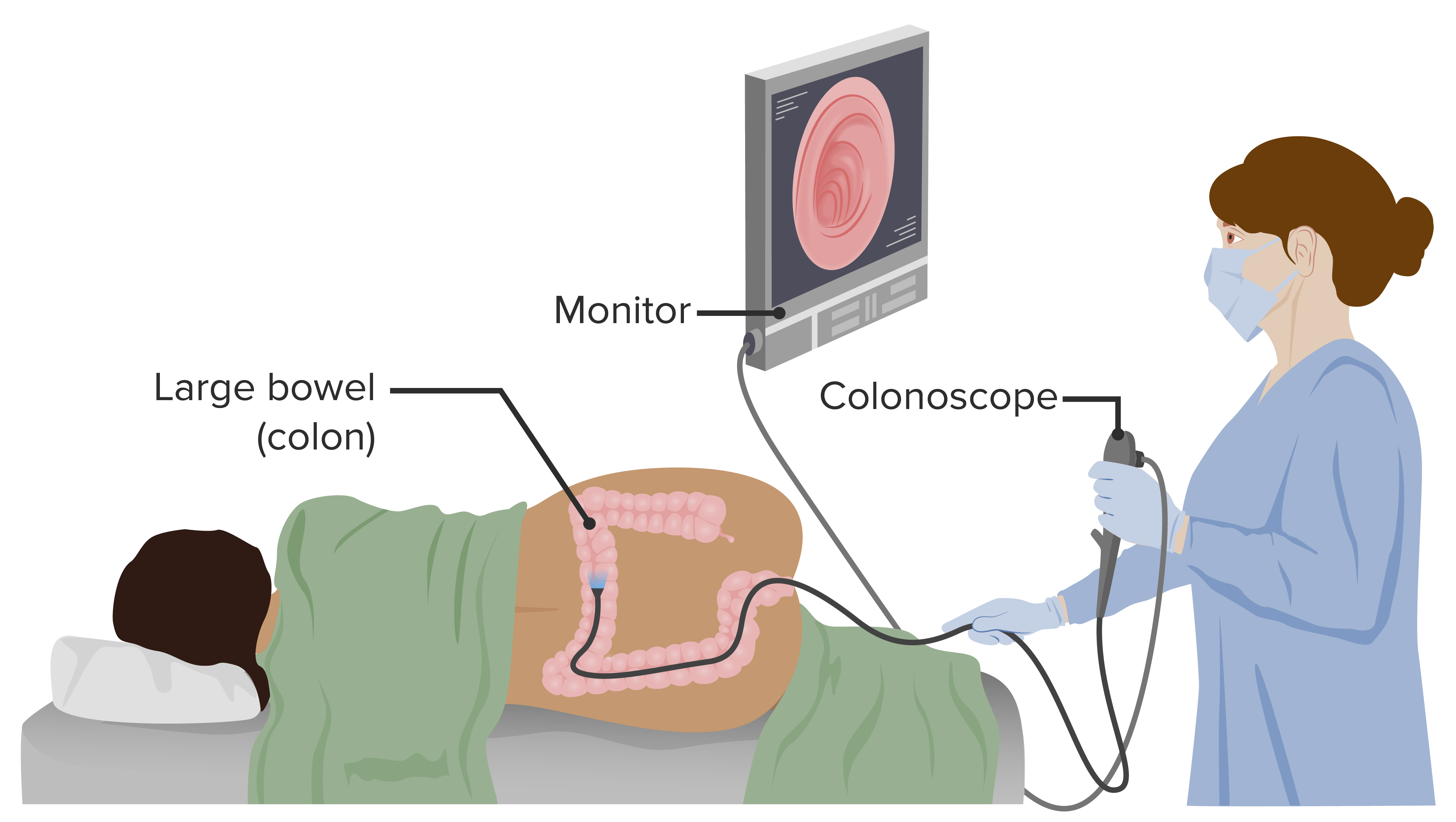

Colonoscopy is a diagnostic procedure that allows visualization of the rectum, colon, and a portion of the terminal ileum. Colonoscopy also has a therapeutic role, allowing biopsy of found lesions.

Image by Lecturio.For an average-risk individual, screening Screening Preoperative Care is initiated at 45 years of age.