Altitude sickness refers to a spectrum of symptoms caused by physiological changes in the human body at altitudes above 2,500 m. Altitude sickness includes acute mountain sickness (AMS), high-altitude cerebral edema Cerebral edema Increased intracellular or extracellular fluid in brain tissue. Cytotoxic brain edema (swelling due to increased intracellular fluid) is indicative of a disturbance in cell metabolism, and is commonly associated with hypoxic or ischemic injuries. An increase in extracellular fluid may be caused by increased brain capillary permeability (vasogenic edema), an osmotic gradient, local blockages in interstitial fluid pathways, or by obstruction of CSF flow (e.g., obstructive hydrocephalus). Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP) (HACE), and high-altitude pulmonary edema Pulmonary edema Pulmonary edema is a condition caused by excess fluid within the lung parenchyma and alveoli as a consequence of a disease process. Based on etiology, pulmonary edema is classified as cardiogenic or noncardiogenic. Patients may present with progressive dyspnea, orthopnea, cough, or respiratory failure. Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). Hypobaric hypoxia Hypoxia Sub-optimal oxygen levels in the ambient air of living organisms. Ischemic Cell Damage is a common pathophysiologic trigger Trigger The type of signal that initiates the inspiratory phase by the ventilator Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. Acute mountain sickness and HACE represent 2 extremes of a neurologic disorder, from benign Benign Fibroadenoma to life-threatening. High-altitude pulmonary edema Pulmonary edema Pulmonary edema is a condition caused by excess fluid within the lung parenchyma and alveoli as a consequence of a disease process. Based on etiology, pulmonary edema is classified as cardiogenic or noncardiogenic. Patients may present with progressive dyspnea, orthopnea, cough, or respiratory failure. Pulmonary Edema is primarily a pulmonary problem, not necessarily preceded by AMS or HACE. The risk of altitude sickness can be reduced by gradual ascent and other precautionary measures, including medications. The symptoms of altitude sickness can be reduced with hyperbaric oxygen Hyperbaric oxygen The therapeutic intermittent administration of oxygen in a chamber at greater than sea-level atmospheric pressures (three atmospheres). It is considered effective treatment for air and gas embolisms, smoke inhalation, acute carbon monoxide poisoning, caisson disease, clostridial gangrene, etc. The list of treatment modalities includes stroke. Decompression Sickness therapy.

Last updated: Mar 11, 2025

All symptomatology Symptomatology Scarlet Fever of AMS and HACE is related to hypoxia Hypoxia Sub-optimal oxygen levels in the ambient air of living organisms. Ischemic Cell Damage. The central nervous system Central nervous system The main information-processing organs of the nervous system, consisting of the brain, spinal cord, and meninges. Nervous System: Anatomy, Structure, and Classification (CNS) is the most sensitive organ to hypoxia Hypoxia Sub-optimal oxygen levels in the ambient air of living organisms. Ischemic Cell Damage.

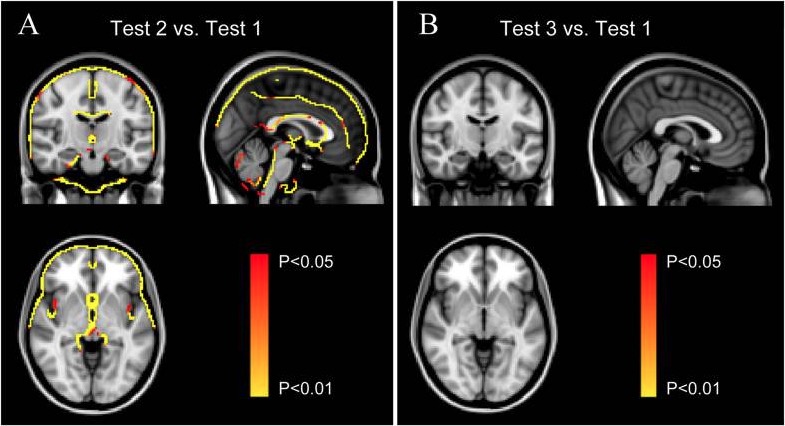

Significant morphometric edge flow indicating brain volume swelling during high-altitude exposure (Test 2A) and 2 months after return to sea level (Test 3B) compared with baseline before ascent to high altitude (Test 1)

Image: “Reversible Brain Abnormalities in People Without Signs of Mountain Sickness During High-Altitude Exposure” by Cunxiu Fan et al. License: CC BY 4.0Both AMS and HACE are diagnosed clinically by noting the characteristic symptoms in a patient who ascends to high altitude.

| Headache Headache The symptom of pain in the cranial region. It may be an isolated benign occurrence or manifestation of a wide variety of headache disorders. Brain Abscess |

|

|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms |

|

| Fatigue Fatigue The state of weariness following a period of exertion, mental or physical, characterized by a decreased capacity for work and reduced efficiency to respond to stimuli. Fibromyalgia/weakness |

|

| Dizziness Dizziness An imprecise term which may refer to a sense of spatial disorientation, motion of the environment, or lightheadedness. Lateral Medullary Syndrome (Wallenberg Syndrome)/ lightheadedness Lightheadedness Hypotension |

|

| AMS clinical functional score: Overall, if you had AMS symptoms, how did they affect your activities? |

|

High-altitude pulmonary edema Pulmonary edema Pulmonary edema is a condition caused by excess fluid within the lung parenchyma and alveoli as a consequence of a disease process. Based on etiology, pulmonary edema is classified as cardiogenic or noncardiogenic. Patients may present with progressive dyspnea, orthopnea, cough, or respiratory failure. Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) is a non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema Pulmonary edema Pulmonary edema is a condition caused by excess fluid within the lung parenchyma and alveoli as a consequence of a disease process. Based on etiology, pulmonary edema is classified as cardiogenic or noncardiogenic. Patients may present with progressive dyspnea, orthopnea, cough, or respiratory failure. Pulmonary Edema (normal capillary wedge pressure) occurring 2–4 days after arrival at high altitude.

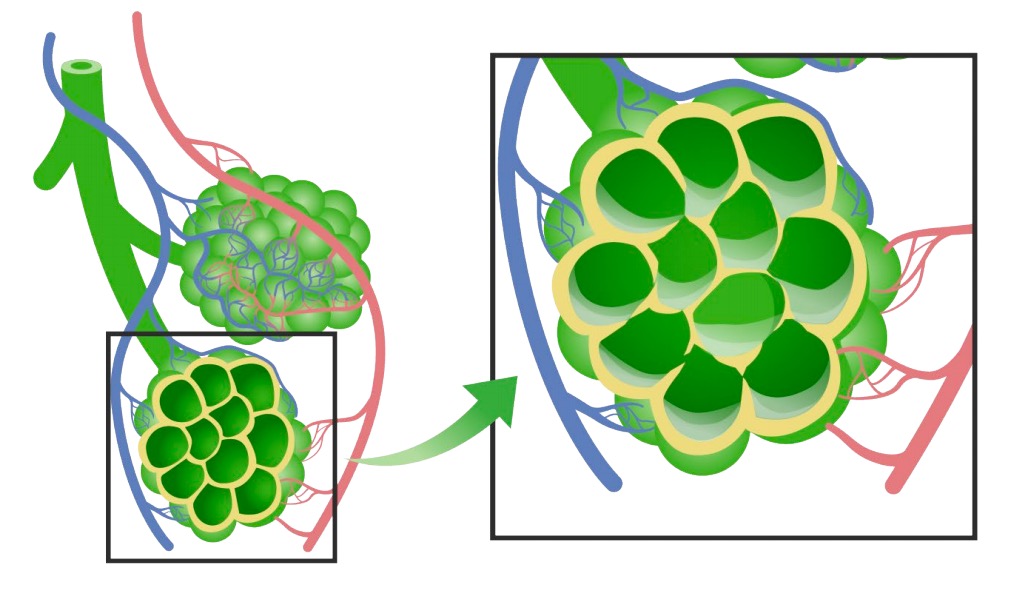

Diagram of pulmonary edema: In HAPE, the alveoli fill up with fluid, interrupting proper gas exchange.

Image by Lecturio.

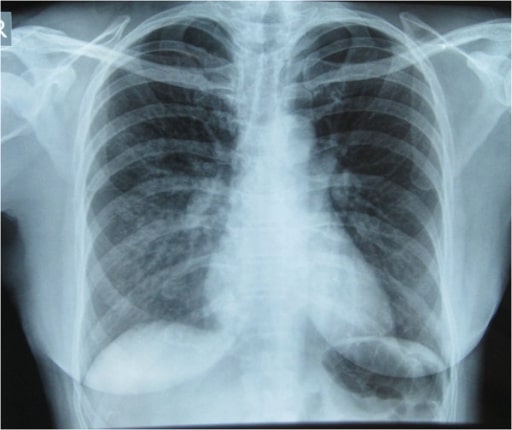

High altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) in a Himalayan trekker: Initial Chest X-ray showing pulmonary infiltrates in the right lung especially in the right mid and lower lung zones indicative of pulmonary edema

Image: “Initial Chest x-ray” by Nepal International Clinic, Travel and Mountain Medicine, Kathmandu, Nepal. License: CC BY 2.0