Renal artery Renal artery A branch of the abdominal aorta which supplies the kidneys, adrenal glands and ureters. Glomerular Filtration stenosis Stenosis Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) (RAS) is the narrowing of one or both renal arteries Arteries Arteries are tubular collections of cells that transport oxygenated blood and nutrients from the heart to the tissues of the body. The blood passes through the arteries in order of decreasing luminal diameter, starting in the largest artery (the aorta) and ending in the small arterioles. Arteries are classified into 3 types: large elastic arteries, medium muscular arteries, and small arteries and arterioles. Arteries: Histology, usually caused by atherosclerotic disease or by fibromuscular dysplasia Fibromuscular dysplasia Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) is a nonatherosclerotic, noninflammatory, medium-sized angiopathy due to fibroplasia of the vessel wall. The condition leads to complications related to arterial stenosis, aneurysm, or dissection. Fibromuscular Dysplasia. If the stenosis Stenosis Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) is severe enough, the stenosis Stenosis Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) causes decreased renal blood flow Renal blood flow The amount of the renal blood flow that is going to the functional renal tissue, i.e., parts of the kidney that are involved in production of urine. Glomerular Filtration, which activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system A blood pressure regulating system of interacting components that include renin; angiotensinogen; angiotensin converting enzyme; angiotensin i; angiotensin ii; and angiotensinase. Renin, an enzyme produced in the kidney, acts on angiotensinogen, an alpha-2 globulin produced by the liver, forming angiotensin I. Angiotensin-converting enzyme, contained in the lung, acts on angiotensin I in the plasma converting it to angiotensin II, an extremely powerful vasoconstrictor. Angiotensin II causes contraction of the arteriolar and renal vascular smooth muscle, leading to retention of salt and water in the kidney and increased arterial blood pressure. In addition, angiotensin II stimulates the release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex, which in turn also increases salt and water retention in the kidney. Angiotensin-converting enzyme also breaks down bradykinin, a powerful vasodilator and component of the kallikrein-kinin system. Adrenal Hormones ( RAAS RAAS A blood pressure regulating system of interacting components that include renin; angiotensinogen; angiotensin converting enzyme; angiotensin i; angiotensin ii; and angiotensinase. Renin, an enzyme produced in the kidney, acts on angiotensinogen, an alpha-2 globulin produced by the liver, forming angiotensin I. Angiotensin-converting enzyme, contained in the lung, acts on angiotensin I in the plasma converting it to angiotensin II, an extremely powerful vasoconstrictor. Angiotensin II causes contraction of the arteriolar and renal vascular smooth muscle, leading to retention of salt and water in the kidney and increased arterial blood pressure. In addition, angiotensin II stimulates the release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex, which in turn also increases salt and water retention in the kidney. Angiotensin-converting enzyme also breaks down bradykinin, a powerful vasodilator and component of the kallikrein-kinin system. Adrenal Hormones) and leads to renovascular hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension (RVH), which only accounts for a small fraction of all cases of hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension. Renovascular hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension can be associated with abdominal bruits, renal insufficiency, or progressive renal atrophy Atrophy Decrease in the size of a cell, tissue, organ, or multiple organs, associated with a variety of pathological conditions such as abnormal cellular changes, ischemia, malnutrition, or hormonal changes. Cellular Adaptation. Diagnosis is by clinical presentation followed by imaging studies, including duplex ultrasonography Duplex ultrasonography Ultrasonography applying the doppler effect combined with real-time imaging. The real-time image is created by rapid movement of the ultrasound beam. A powerful advantage of this technique is the ability to estimate the velocity of flow from the doppler shift frequency. Hypercoagulable States, magnetic resonance angiography Angiography Radiography of blood vessels after injection of a contrast medium. Cardiac Surgery ( MRA MRA Imaging of the Heart and Great Vessels), computed tomography angiography Angiography Radiography of blood vessels after injection of a contrast medium. Cardiac Surgery ( CTA CTA A non-invasive method that uses a ct scanner for capturing images of blood vessels and tissues. A contrast material is injected, which helps produce detailed images that aid in diagnosing vascular diseases. Pulmonary Function Tests), and sometimes catheter-based angiography Angiography Radiography of blood vessels after injection of a contrast medium. Cardiac Surgery. Revascularization Revascularization Thromboangiitis Obliterans (Buerger Disease) is usually reserved for cases in which medical therapy has failed.

Last updated: Jan 19, 2025

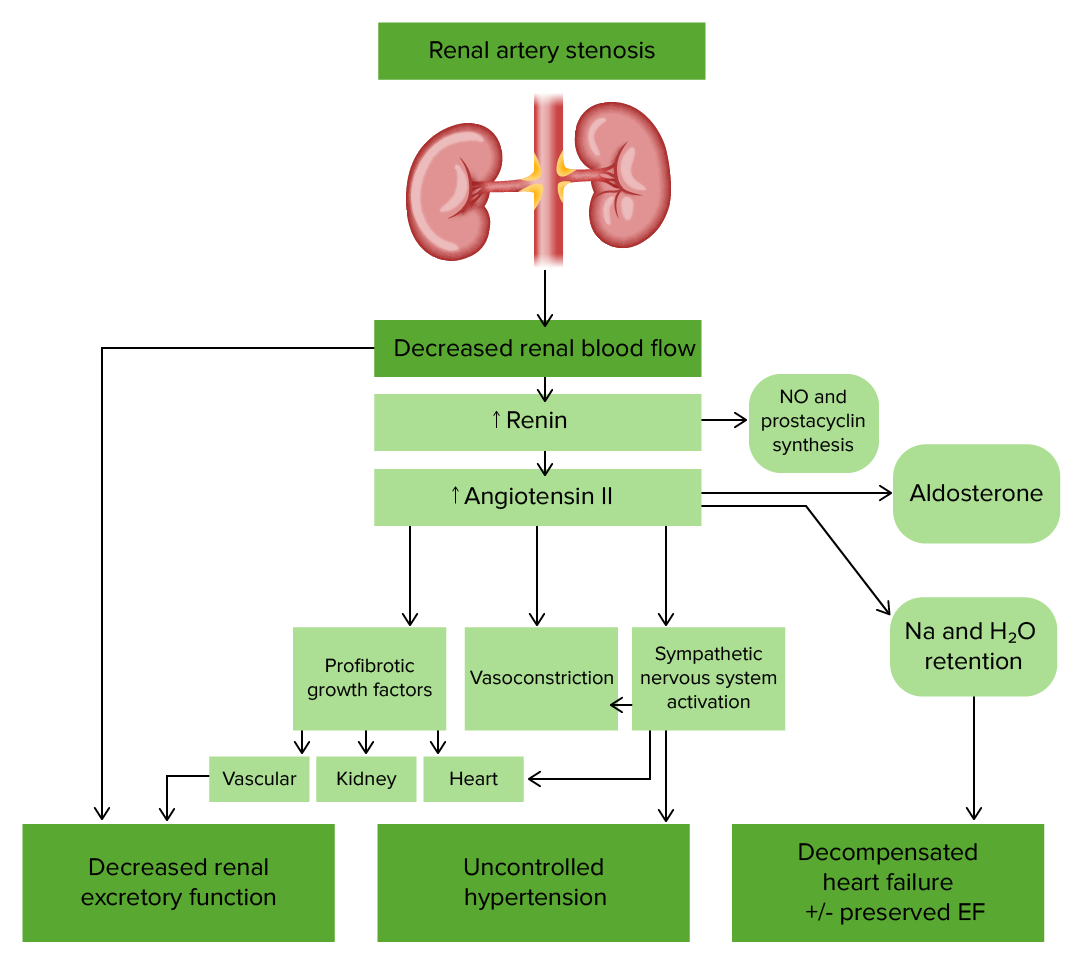

Pathophysiology of renal artery stenosis

Image by Lecturio.Additional diagnostic tests Diagnostic tests Diagnostic tests are important aspects in making a diagnosis. Some of the most important epidemiological values of diagnostic tests include sensitivity and specificity, false positives and false negatives, positive and negative predictive values, likelihood ratios, and pre-test and post-test probabilities. Epidemiological Values of Diagnostic Tests can be used in the following cases:

However, the tests are expensive and may have serious side effects, especially if renal insufficiency is present.

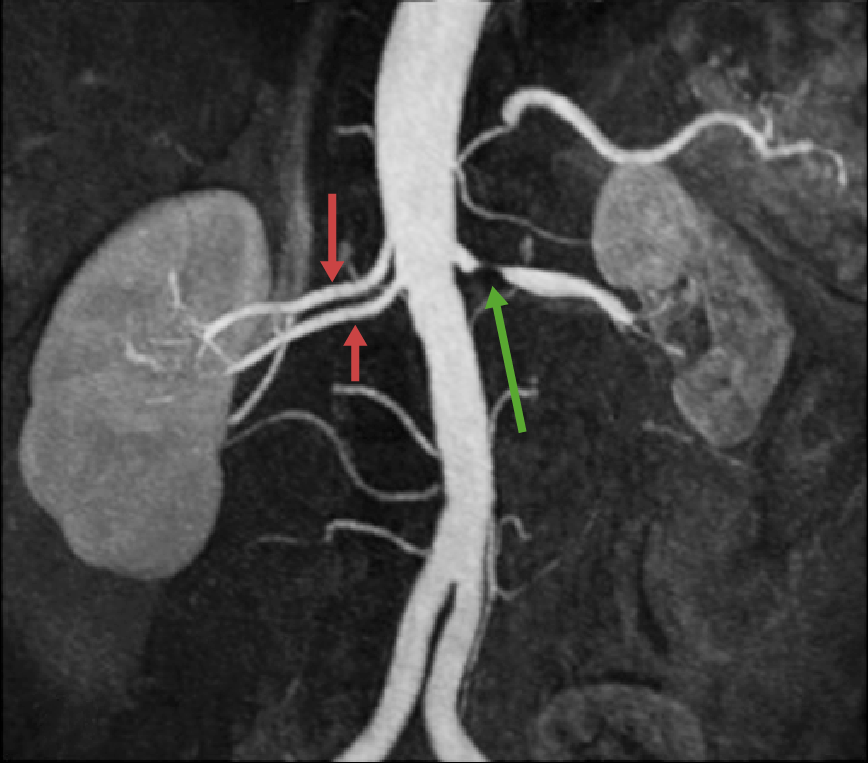

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showing high-grade renal artery stenosis of the left renal artery (green arrow), which caused severe renal ischemia/infarction followed by scarring and contraction. The right kidney appears to be unaffected and of normal size, with 2 renal arteries (red arrows). Multiple or accessory renal arteries are present in about 25% of the general population.

Image: “Assessment of the kidneys: magnetic resonance angiography, perfusion and diffusion” by Attenberger UI, Morelli JN, Schoenberg SO, Michaely HJ. License: CC BY 2.0, edited by Lecturio.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showing left renal artery obstruction (the end result of severe progressive stenosis) causing atrophy of the left kidney, which is supplied by an accessory renal artery, located inferior to the stump of the left main renal artery visualized by the contrast medium. There is normal perfusion and function of the right kidney.

Image: “A case of treatable hypertension: fibromuscular dysplasia of renal arteries” by Ralapanawa DM, Jayawickreme KP, Ekanayake EM. License: CC BY 4.0.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showing left renal artery stenosis from a 66-year-old man with a history of hypertension. The left kidney is atrophic, with few patent arteries remaining visible.

Image: “Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in systemic hypertension” by Alicia M Maceira and Raad H Mohiaddin. License: CC BY 2.0.

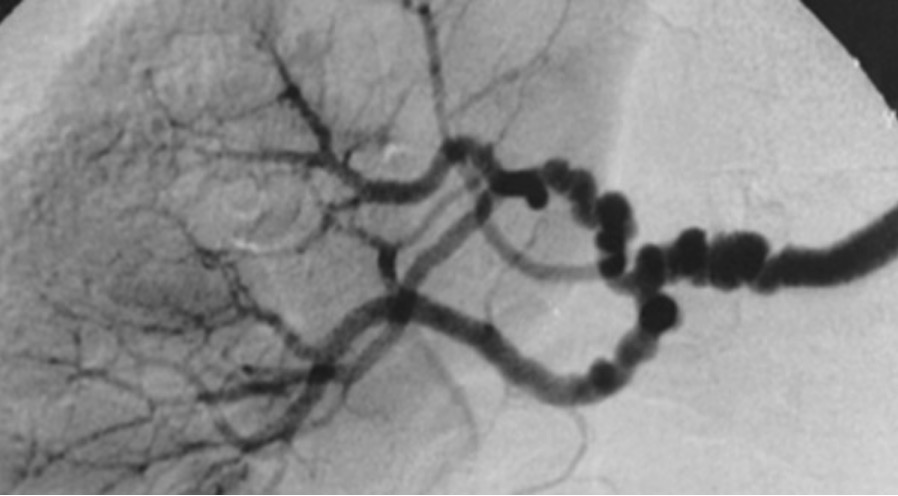

Angiography image showing the “string of beads” appearance of branches of the renal artery in a patient with multifocal fibromuscular dysplasia

Image: “String-of-beads” by Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, AP-HP, Université Paris Descartes, Faculté de Médecine, INSERM Unit 772, Collège de France, Paris, France. License: CC BY 2.0The most common type of hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension, with an unknown etiology. In 2017, the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association American Heart Association A voluntary organization concerned with the prevention and treatment of heart and vascular diseases. Heart Failure (ACC/AHA) revised their definitions, which may vary among different countries:

Five to ten percent of all cases of hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension include the following conditions: