Slipped capital femoral epiphysis Epiphysis The head of a long bone that is separated from the shaft by the epiphyseal plate until bone growth stops. At that time, the plate disappears and the head and shaft are united. Bones: Structure and Types (SCFE) is an orthopedic disorder of early adolescence characterized by the pathologic “slipping” or displacement Displacement The process by which an emotional or behavioral response that is appropriate for one situation appears in another situation for which it is inappropriate. Defense Mechanisms of the femoral head, or epiphysis Epiphysis The head of a long bone that is separated from the shaft by the epiphyseal plate until bone growth stops. At that time, the plate disappears and the head and shaft are united. Bones: Structure and Types, on the femoral neck Neck The part of a human or animal body connecting the head to the rest of the body. Peritonsillar Abscess. Considered a type I Salter-Harris growth plate fracture Fracture A fracture is a disruption of the cortex of any bone and periosteum and is commonly due to mechanical stress after an injury or accident. Open fractures due to trauma can be a medical emergency. Fractures are frequently associated with automobile accidents, workplace injuries, and trauma. Overview of Bone Fractures, SCFE affects boys twice as often as girls. Thought to be due to a combination of biomechanical and endocrine factors, diagnosis is made with hip X-rays X-rays X-rays are high-energy particles of electromagnetic radiation used in the medical field for the generation of anatomical images. X-rays are projected through the body of a patient and onto a film, and this technique is called conventional or projectional radiography. X-rays and treatment ranges from conservative to surgical. Prognosis Prognosis A prediction of the probable outcome of a disease based on a individual's condition and the usual course of the disease as seen in similar situations. Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas depends on the severity of the slip or displacement Displacement The process by which an emotional or behavioral response that is appropriate for one situation appears in another situation for which it is inappropriate. Defense Mechanisms.

Last updated: Feb 28, 2025

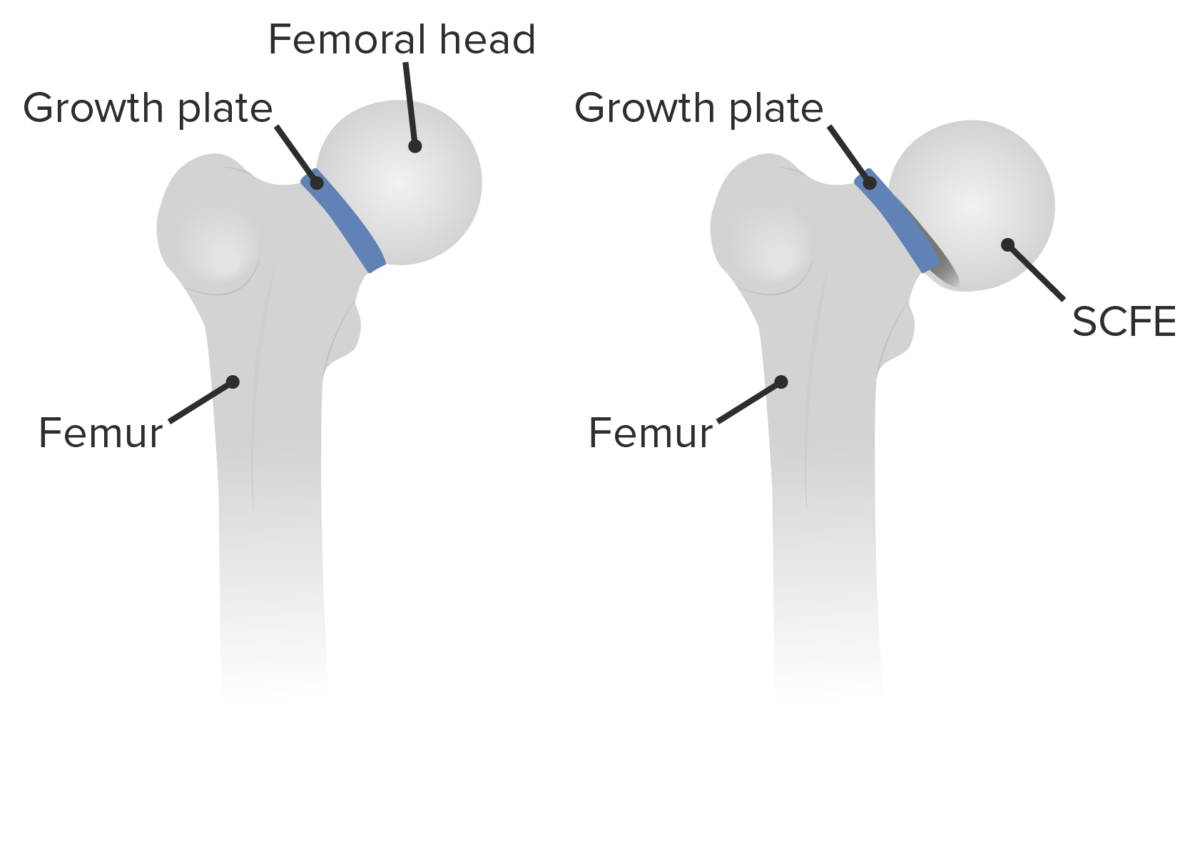

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis Epiphysis The head of a long bone that is separated from the shaft by the epiphyseal plate until bone growth stops. At that time, the plate disappears and the head and shaft are united. Bones: Structure and Types (SCFE) is a hip disorder common in adolescence that features the displacement Displacement The process by which an emotional or behavioral response that is appropriate for one situation appears in another situation for which it is inappropriate. Defense Mechanisms of the capital epiphysis Epiphysis The head of a long bone that is separated from the shaft by the epiphyseal plate until bone growth stops. At that time, the plate disappears and the head and shaft are united. Bones: Structure and Types of the femoral head through the growth plate (physis) in relationship to the femoral neck Neck The part of a human or animal body connecting the head to the rest of the body. Peritonsillar Abscess.

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: displacement of the capital femoral epiphysis of the femoral head through the growth plate (physis) in relationship to the femoral neck

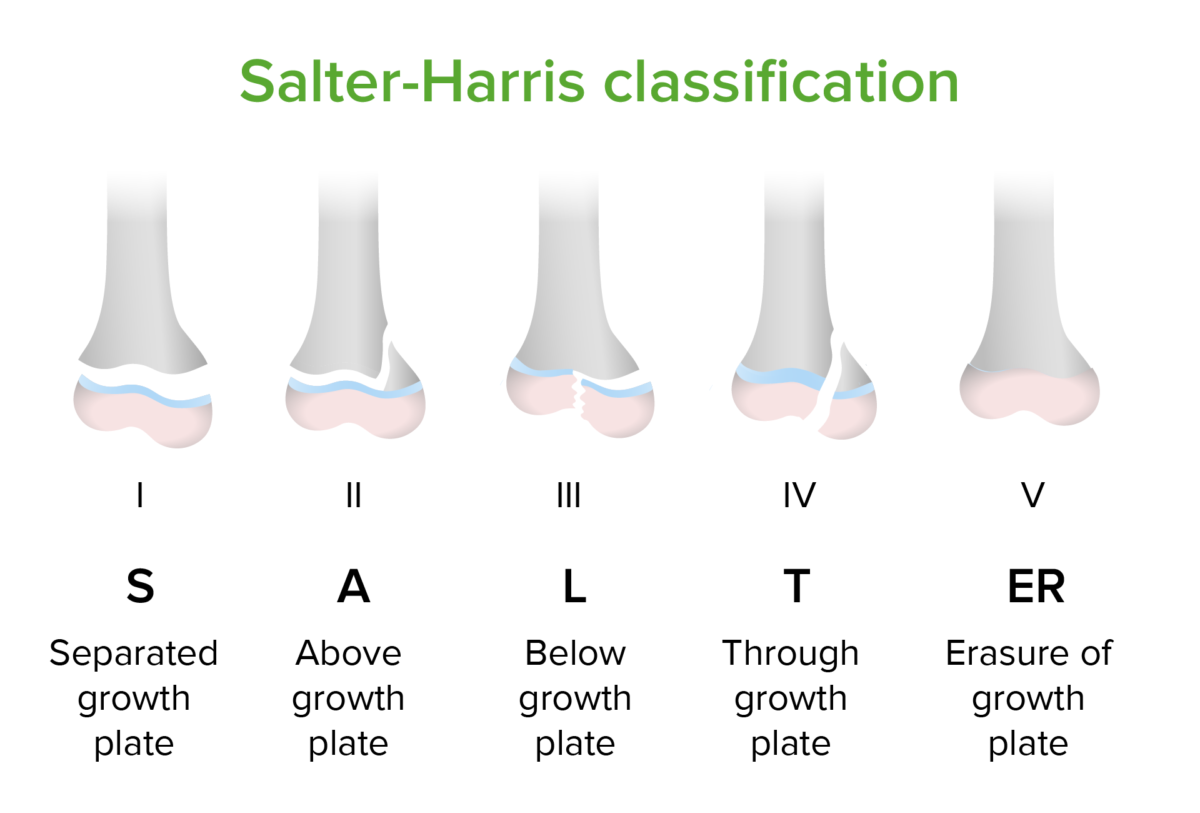

Image by Lecturio.Slipped capital femoral epiphysis Epiphysis The head of a long bone that is separated from the shaft by the epiphyseal plate until bone growth stops. At that time, the plate disappears and the head and shaft are united. Bones: Structure and Types (SCFE) is considered a Salter-Harris type 1 Type 1 Spinal Muscular Atrophy fracture Fracture A fracture is a disruption of the cortex of any bone and periosteum and is commonly due to mechanical stress after an injury or accident. Open fractures due to trauma can be a medical emergency. Fractures are frequently associated with automobile accidents, workplace injuries, and trauma. Overview of Bone Fractures, because SCFE is a transverse fracture Transverse Fracture Overview of Bone Fractures through the growth plate or physis.

Salter-Harris classification of epiphyseal fractures

The epiphyseal plate is the growth center of long bones. Fractures incurred during childhood that involve the epiphyseal plate are concerning because such fractures may damage the blood supply to the plate, affecting the bone’s growth over time. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis is an example of a type 1 fracture of the femoral epiphysis with subsequent slipping of the fractured bone.

There are several classification systems for SCFE:

The causes of SCFE are multifactorial, a combination of endocrine and biomechanical factors. Excessive mechanical forces causing more shearing forces Shearing forces Vascular Resistance, Flow, and Mean Arterial Pressure to be applied to the femoral neck Neck The part of a human or animal body connecting the head to the rest of the body. Peritonsillar Abscess result in the failure of a susceptible (weakened) physis.

Repetitive shear forces applied to a weakened physis result in fracture Fracture A fracture is a disruption of the cortex of any bone and periosteum and is commonly due to mechanical stress after an injury or accident. Open fractures due to trauma can be a medical emergency. Fractures are frequently associated with automobile accidents, workplace injuries, and trauma. Overview of Bone Fractures and slipping. As slippage progresses, the metaphysis Metaphysis Bones: Structure and Types translates anteriorly and superiorly while rotating externally; the epiphysis Epiphysis The head of a long bone that is separated from the shaft by the epiphyseal plate until bone growth stops. At that time, the plate disappears and the head and shaft are united. Bones: Structure and Types remains in the acetabulum.

Children who present with SCFE typically complain of groin Groin The external junctural region between the lower part of the abdomen and the thigh. Male Genitourinary Examination and anterior thigh Thigh The thigh is the region of the lower limb found between the hip and the knee joint. There is a single bone in the thigh called the femur, which is surrounded by large muscles grouped into 3 fascial compartments. Thigh: Anatomy pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways, and demonstrate an altered gait Gait Manner or style of walking. Neurological Examination.

The diagnosis of SCFE is performed through a combination of history, physical examination, and plain film X-rays X-rays X-rays are high-energy particles of electromagnetic radiation used in the medical field for the generation of anatomical images. X-rays are projected through the body of a patient and onto a film, and this technique is called conventional or projectional radiography. X-rays.

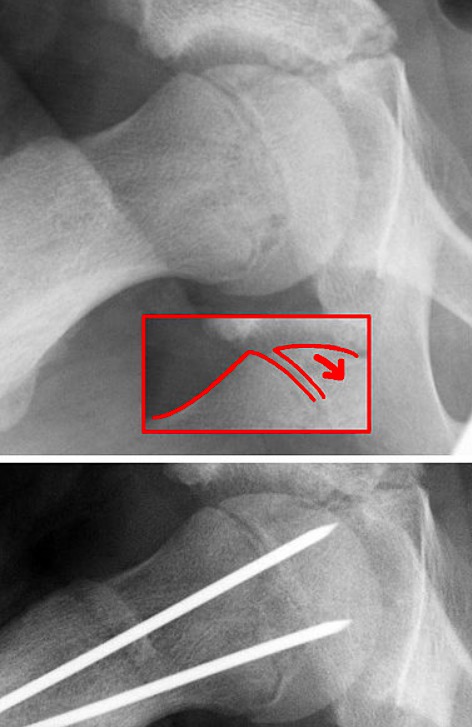

Anteroposterior radiograph showing a moderate-grade SCFE and Risser grade IV calcification

Image: “Pre-operative radiograph” by Danao Marquez, corresponding author Eric Harb, and Hugo Vilchis . License: CC BY 4.0.

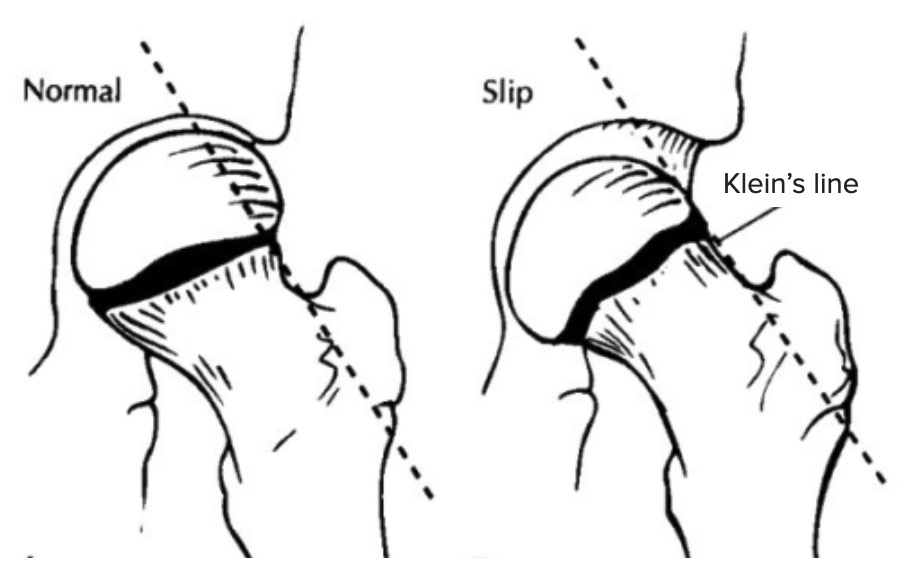

Klein’s line in SCFE

Diagram shows the difference between a normal hip (left) and a hip with SCFE, or SCFE, (right) guided by Klein’s line. Klein’s line is drawn on AP hip X-rays along the superior margin of the femoral neck. In cases of SCFE, the line does not cut through the femoral head, as seen on the right.

The treatment involves immediate non–weight-bearing status and referral to orthopedic surgery:

Surgical correction of SCFE

Image: “Epilys” by Dr. Jochen Lengerke. License: Public domain.

Percutaneous screw fixation through the femoral neck, engaging the physis

Image: “X-ray of the left hip after in situ fixation” by Department of Orthopaedics, Postbus 501, Alkmaar, AM, 1800, The Netherlands. License: CC BY 2.0.