Vascular rings Vascular Rings Pediatric Vomiting are a group of rare malformations featuring congenital abnormalities Congenital Abnormalities Malformations of organs or body parts during development in utero. Omphalocele of the aortic arch Aortic arch Mediastinum and Great Vessels: Anatomy. The aberrant arteries Arteries Arteries are tubular collections of cells that transport oxygenated blood and nutrients from the heart to the tissues of the body. The blood passes through the arteries in order of decreasing luminal diameter, starting in the largest artery (the aorta) and ending in the small arterioles. Arteries are classified into 3 types: large elastic arteries, medium muscular arteries, and small arteries and arterioles. Arteries: Histology often form a ring around the esophagus Esophagus The esophagus is a muscular tube-shaped organ of around 25 centimeters in length that connects the pharynx to the stomach. The organ extends from approximately the 6th cervical vertebra to the 11th thoracic vertebra and can be divided grossly into 3 parts: the cervical part, the thoracic part, and the abdominal part. Esophagus: Anatomy and trachea Trachea The trachea is a tubular structure that forms part of the lower respiratory tract. The trachea is continuous superiorly with the larynx and inferiorly becomes the bronchial tree within the lungs. The trachea consists of a support frame of semicircular, or C-shaped, rings made out of hyaline cartilage and reinforced by collagenous connective tissue. Trachea: Anatomy, putting pressure on these structures. Clinical symptoms range from stridor Stridor Laryngomalacia and Tracheomalacia, respiratory distress, and/or dysphagia Dysphagia Dysphagia is the subjective sensation of difficulty swallowing. Symptoms can range from a complete inability to swallow, to the sensation of solids or liquids becoming "stuck." Dysphagia is classified as either oropharyngeal or esophageal, with esophageal dysphagia having 2 sub-types: functional and mechanical. Dysphagia in neonates, to asymptomatic forms, noted incidentally in adults. Diagnosis is confirmed through X-ray X-ray Penetrating electromagnetic radiation emitted when the inner orbital electrons of an atom are excited and release radiant energy. X-ray wavelengths range from 1 pm to 10 nm. Hard x-rays are the higher energy, shorter wavelength x-rays. Soft x-rays or grenz rays are less energetic and longer in wavelength. The short wavelength end of the x-ray spectrum overlaps the gamma rays wavelength range. The distinction between gamma rays and x-rays is based on their radiation source. Pulmonary Function Tests and echocardiography Echocardiography Ultrasonic recording of the size, motion, and composition of the heart and surrounding tissues. The standard approach is transthoracic. Tricuspid Valve Atresia (TVA), but may be further defined with a computed tomographic (CT) scan. Definitive treatment is surgical, and the prognosis Prognosis A prediction of the probable outcome of a disease based on a individual's condition and the usual course of the disease as seen in similar situations. Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas is excellent as clinical recovery is immediate.

Last updated: Jan 7, 2025

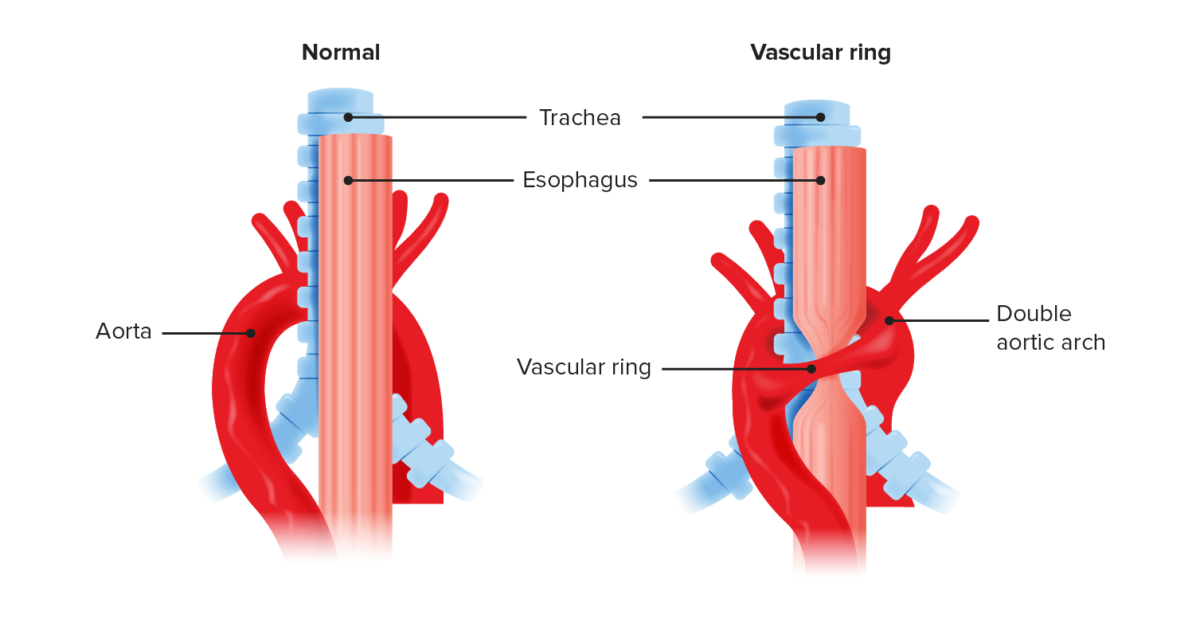

A vascular ring Vascular Ring Pediatric Chest Abnormalities is a congenital malformation in which the esophagus Esophagus The esophagus is a muscular tube-shaped organ of around 25 centimeters in length that connects the pharynx to the stomach. The organ extends from approximately the 6th cervical vertebra to the 11th thoracic vertebra and can be divided grossly into 3 parts: the cervical part, the thoracic part, and the abdominal part. Esophagus: Anatomy and trachea Trachea The trachea is a tubular structure that forms part of the lower respiratory tract. The trachea is continuous superiorly with the larynx and inferiorly becomes the bronchial tree within the lungs. The trachea consists of a support frame of semicircular, or C-shaped, rings made out of hyaline cartilage and reinforced by collagenous connective tissue. Trachea: Anatomy are encircled by an aberrant aorta Aorta The main trunk of the systemic arteries. Mediastinum and Great Vessels: Anatomy.

Anatomical recreation of a vascular ring compared to normal anatomy

Double aortic arch causes compression of the trachea and esophagus. Vascular rings often compress the trachea leading to a degree of tracheomalacia.

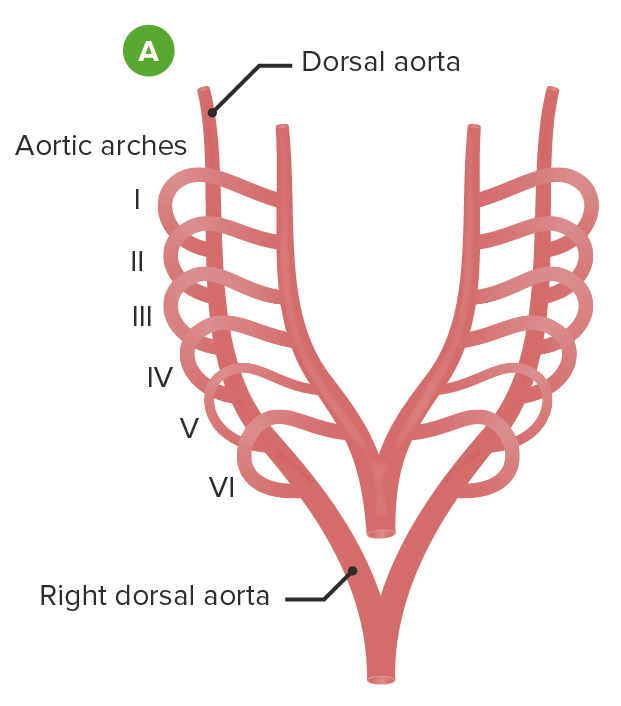

Embryological formation of the aortic arch and associated blood vessel: The vasculature that will become the aortic arch and all of its associated vessels begins as 6 paired sets of aortic arches, each associated with a branchial arch (A).

Image by Lecturio.

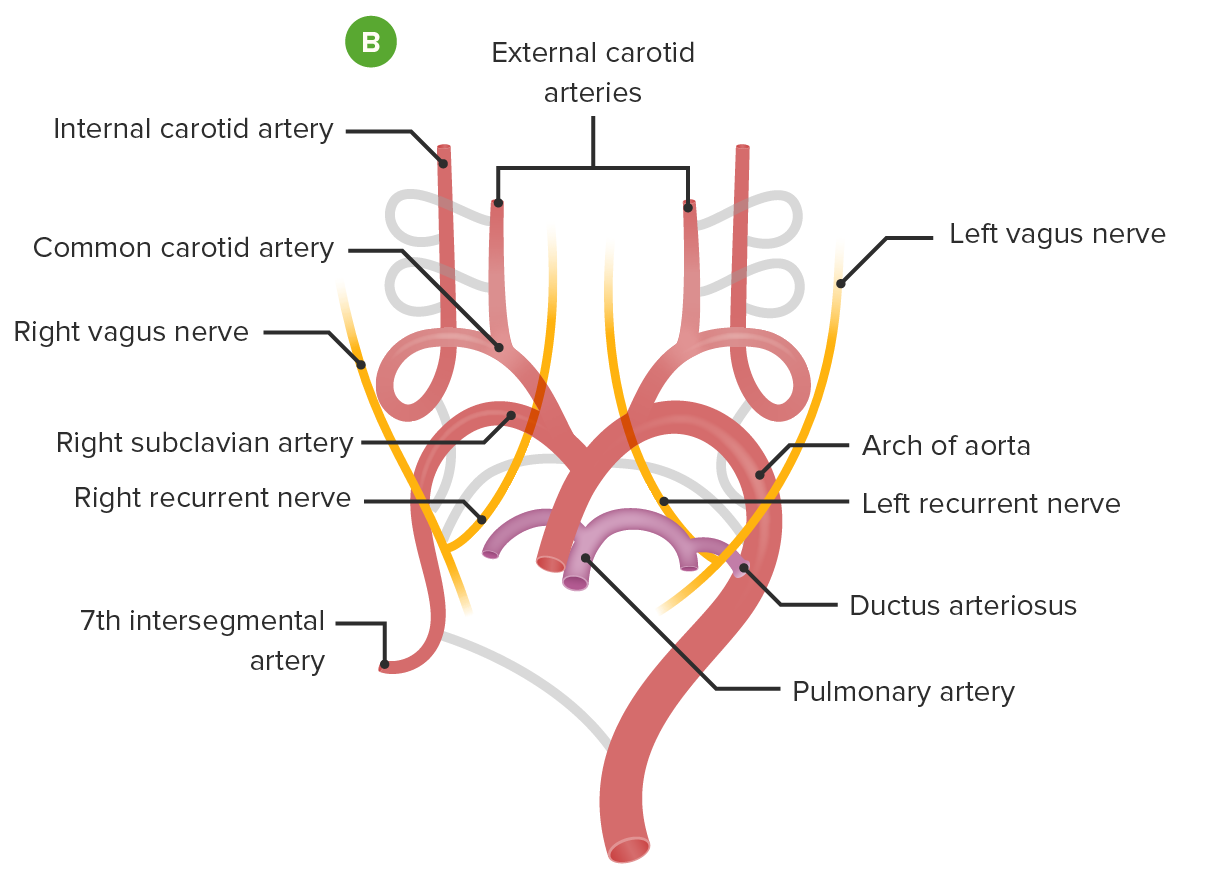

Embryological formation of the aortic arch and associated blood vessel: Involution of some arches and incorporation and growth of others creates the adult structures of the aortic arch and pulmonary arteries (B).

Image by Lecturio.

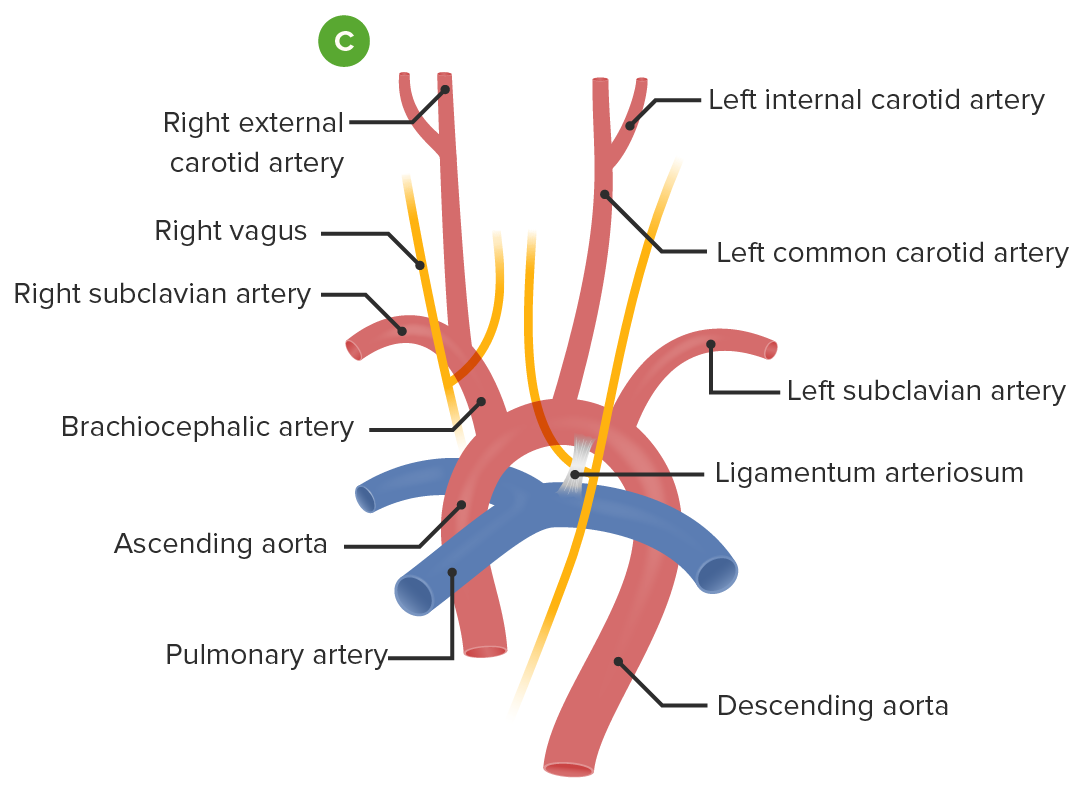

Embryological formation of the aortic arch and associated blood vessel: In the adult conformation, the aortic arch courses right to left, passing posteriorly to the esophagus and trachea (C).

Image by Lecturio.Although the clinical symptoms and treatment approach are the same, there are multiple ways in which the development of the aortic arch Aortic arch Mediastinum and Great Vessels: Anatomy can give rise to a vascular ring Vascular Ring Pediatric Chest Abnormalities. Each variant is unique in its anatomy and embryological origin.

The severity of symptoms depends on the degree of compression Compression Blunt Chest Trauma of the trachea Trachea The trachea is a tubular structure that forms part of the lower respiratory tract. The trachea is continuous superiorly with the larynx and inferiorly becomes the bronchial tree within the lungs. The trachea consists of a support frame of semicircular, or C-shaped, rings made out of hyaline cartilage and reinforced by collagenous connective tissue. Trachea: Anatomy/ esophagus Esophagus The esophagus is a muscular tube-shaped organ of around 25 centimeters in length that connects the pharynx to the stomach. The organ extends from approximately the 6th cervical vertebra to the 11th thoracic vertebra and can be divided grossly into 3 parts: the cervical part, the thoracic part, and the abdominal part. Esophagus: Anatomy.

Examination may be normal, but usually in infants:

CT axial image demonstrates a double aortic arch and encircling of the trachea.

Image: “Detection of airway anomalies in pediatric patients with cardiovascular anomalies with low dose prospective ECG-gated dual-source CT” by Jiao H, Xu Z, Wu L, Cheng Z, Ji X, Zhong H, Meng C. License: CC BY 4.0