Cervical cancer, or invasive cervical carcinoma (ICC), is the 3rd most common gynecologic cancer in women in the world, with > 50% of the cases being fatal. In the United States, ICC is the 13th most common cancer and the cause of < 3% of all cancer deaths due to the slow progression of precursor lesions and, more importantly, effective cancer screening Screening Preoperative Care. There are 2 major histologic types of ICC: squamous cell carcinoma Squamous cell carcinoma Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is caused by malignant proliferation of atypical keratinocytes. This condition is the 2nd most common skin malignancy and usually affects sun-exposed areas of fair-skinned patients. The cancer presents as a firm, erythematous, keratotic plaque or papule. Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) (SCC) and adenocarcinoma. High-risk human papillomaviruses (hrHPVs) cause > 99% of SCCs and > 85% of adenocarcinomas. Early cervical neoplasia is asymptomatic, and diagnosis is made using routine screening Screening Preoperative Care methods, including the cervical Papanicolaou test with cytology, hrHPV testing, and biopsy Biopsy Removal and pathologic examination of specimens from the living body. Ewing Sarcoma. Treatment of precursor or dysplastic lesions depends on the severity of the dysplasia and the age of the patient. Management of ICCs depends on the stage and varies from excisional biopsy Biopsy Removal and pathologic examination of specimens from the living body. Ewing Sarcoma by cervical cone biopsy Biopsy Removal and pathologic examination of specimens from the living body. Ewing Sarcoma for microinvasive ICC to radical hysterectomy for more advanced cases. If there is extracervical spread, radiation Radiation Emission or propagation of acoustic waves (sound), electromagnetic energy waves (such as light; radio waves; gamma rays; or x-rays), or a stream of subatomic particles (such as electrons; neutrons; protons; or alpha particles). Osteosarcoma and chemotherapy Chemotherapy Osteosarcoma would be recommended.

Last updated: May 17, 2024

High-risk human papillomaviruses (hrHPVs, “oncogenic viruses Viruses Minute infectious agents whose genomes are composed of DNA or RNA, but not both. They are characterized by a lack of independent metabolism and the inability to replicate outside living host cells. Virology”) are strongly associated with high-grade lesions and progression to invasive cancer.

HPV-related:

Non–HPV-related:

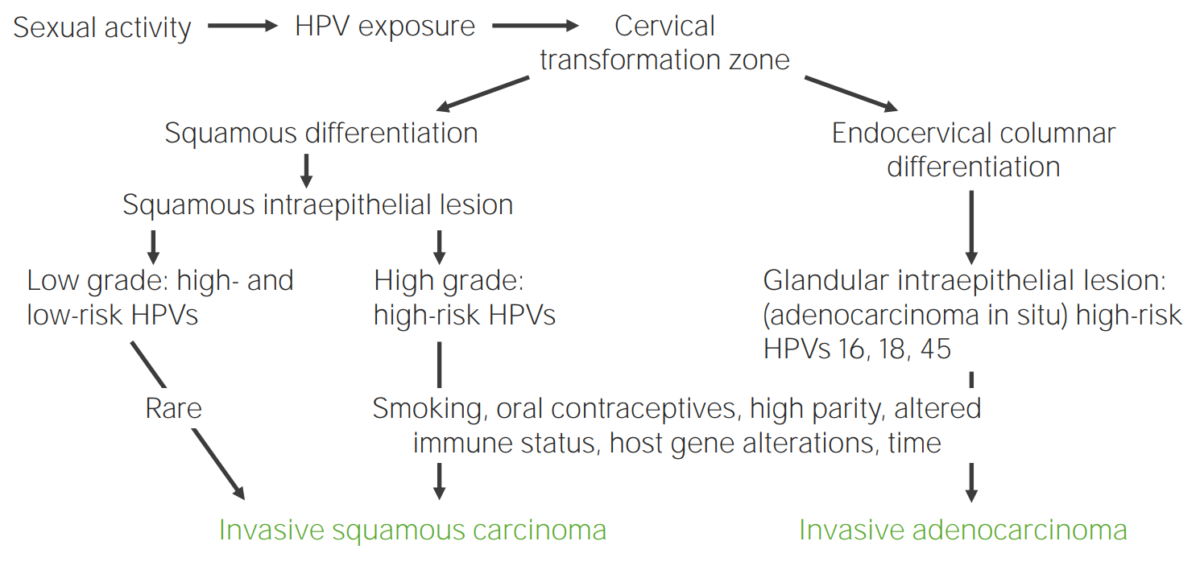

Diagram showcasing the pathogenesis of cervical carcinoma due to HPV

Image by Lecturio.

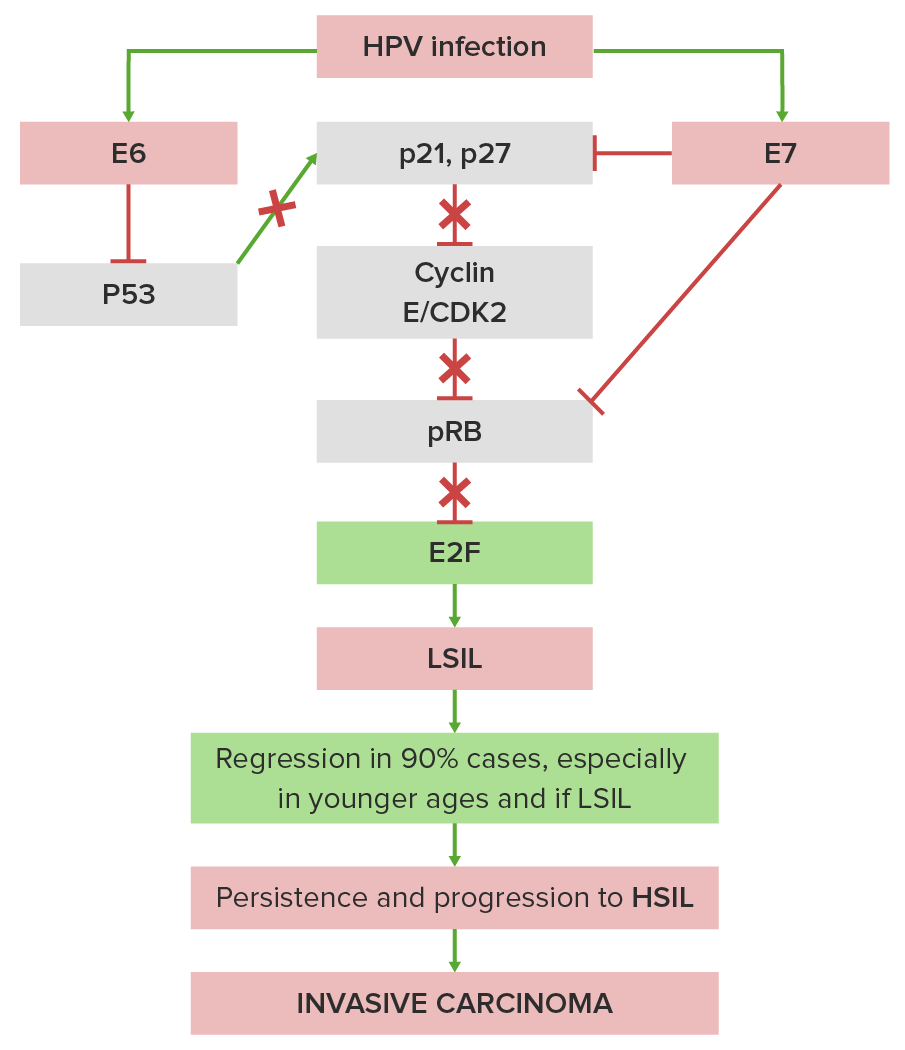

Simplified pathogenesis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer:

E6 protein from HPV blocks the tumor suppressor p53 protein (the “guardian of the genome”), which interferes with cellular defenses, and E7 from HPV blocks the tumor suppressor RB protein, which permits uninhibited cell growth. This upsets the usually controlled balance between normal growth factors (e.g., by epidermal growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor) and normal growth inhibitors (e.g., by pTGF-β (transforming growth factor β) and p53).

X indicates where HPV blocks the normal stimulatory or inhibitory pathways.

CDK2: cyclin-dependent kinase 2

SIL classification:

Gross appearance of HSIL:

Microscopic appearance:

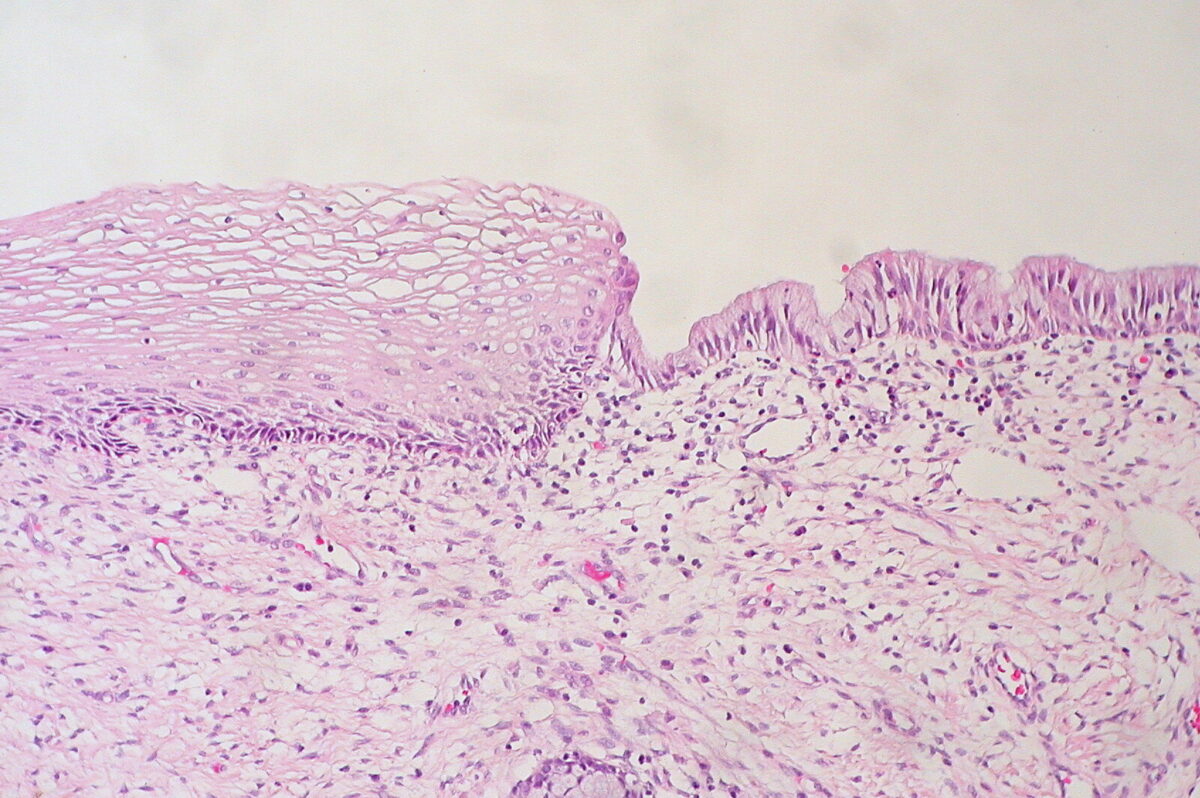

Histologic findings of a normal cervix

Image: “Cervix Uteri: Normal Squamocolumnar Junction” by Ed Uthman. License: CC BY 2.0

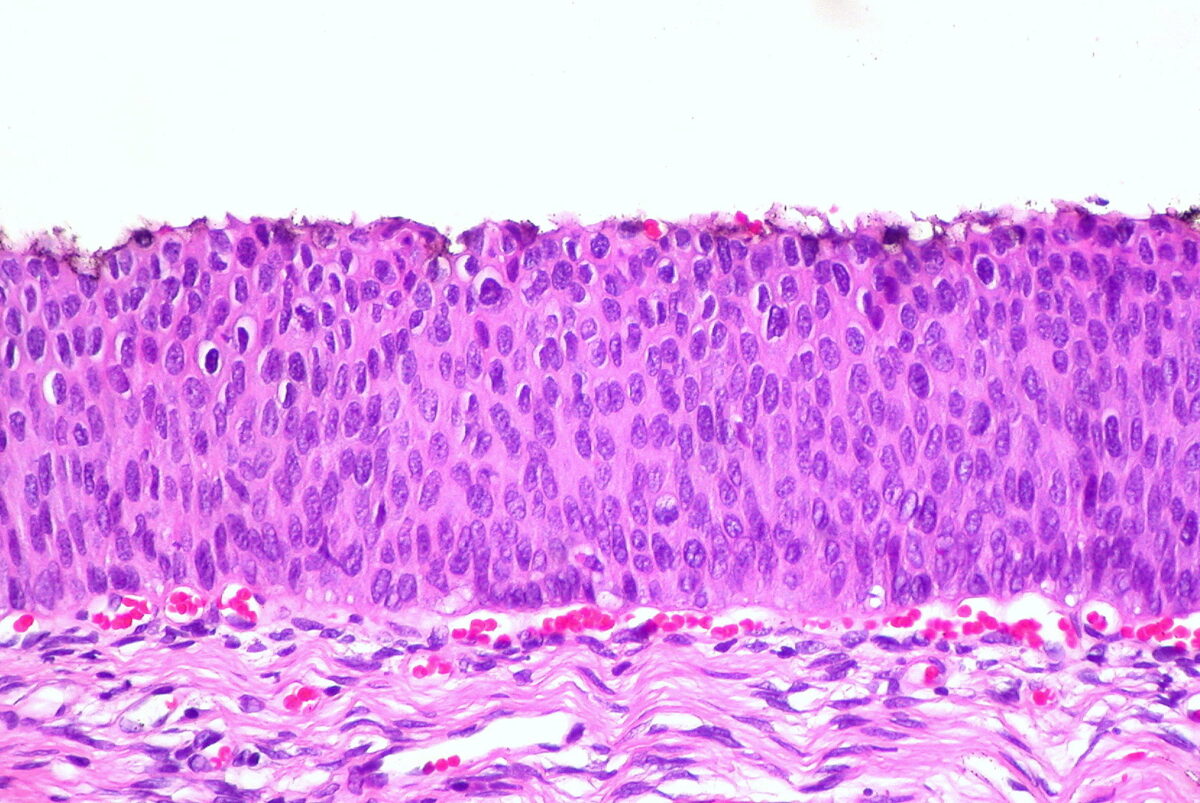

Histologic findings in HSIL/CIN 3

Image: “CIN 3, Cervical Biopsy” by Ed Uthman. License: CC BY 2.0

Examples of squamous cell findings from cervical cytology:

(a): normal cell

(b): atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

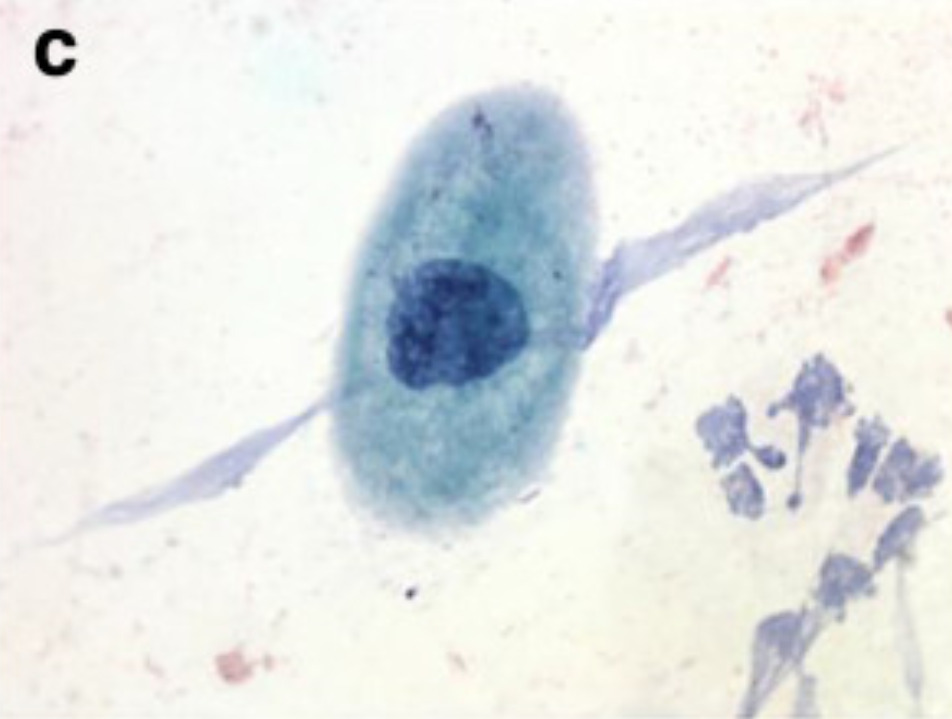

Examples of squamous cell findings from cervical cytology:

(c): LSIL

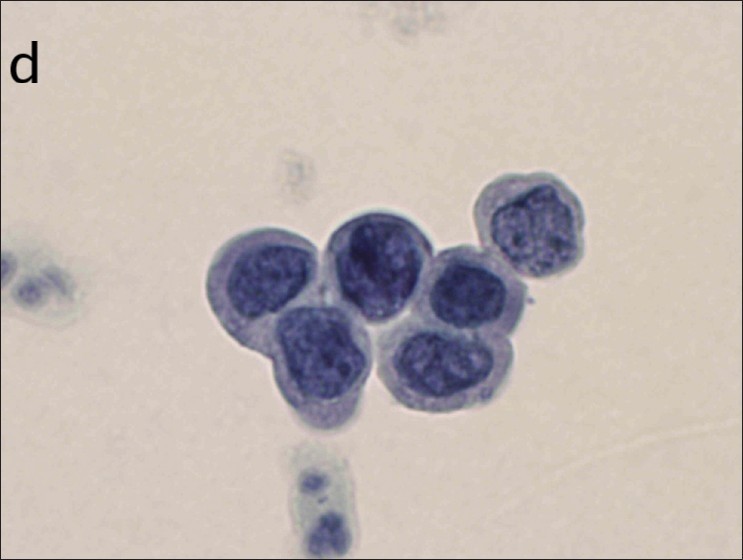

Examples of squamous cell findings from cervical cytology:

(d): HSIL

Gross appearance:

Microscopic appearance:

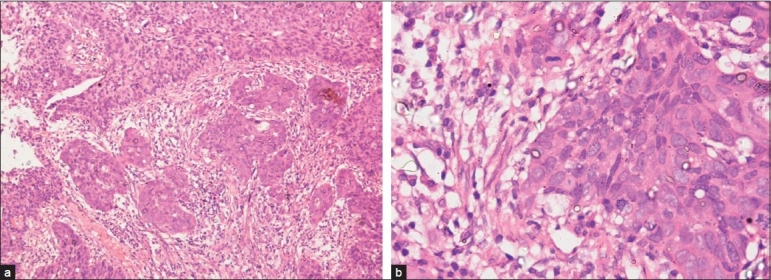

Micrograph images of cervical carcinoma:

(a): histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen showing large-cell nonkeratinizing SCC

(b): higher-power histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy showing large-cell nonkeratinizing SCC

Signs and symptoms caused by tumor Tumor Inflammation extension Extension Examination of the Upper Limbs and invasion:

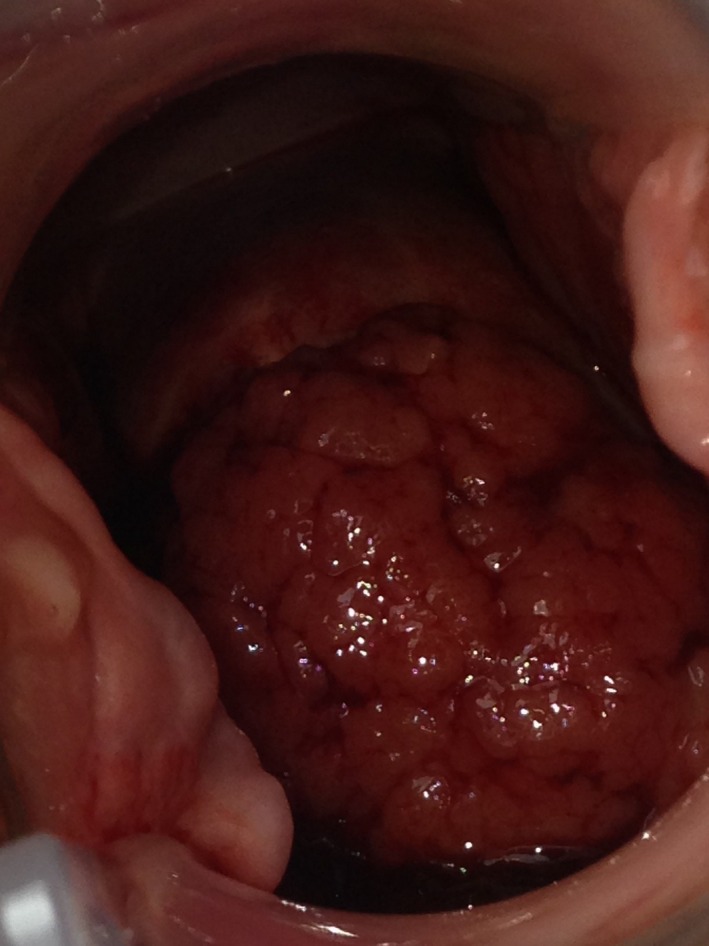

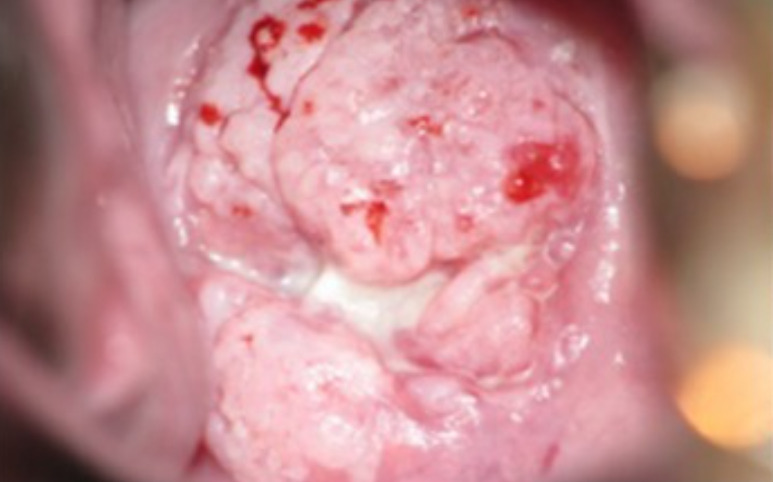

A progressive cervical adenocarcinoma:

The image shows a rapidly progressing mass protruding from the cervix.

The diagnosis of ICC is made by histologic examination of a cervical biopsy Biopsy Removal and pathologic examination of specimens from the living body. Ewing Sarcoma.

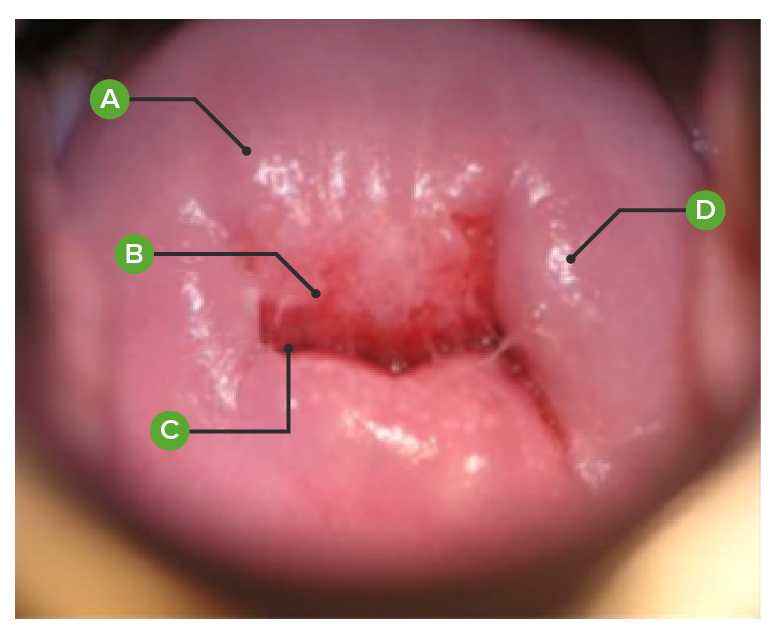

Normal cervix, as viewed on colposcopy:

(A): exocervical mucosa

(B): transformation zone between the exocervix and endocervix

(C): endocervical mucosa appearing at the external cervical os

(D): nabothian cyst (mucus-filled cyst)

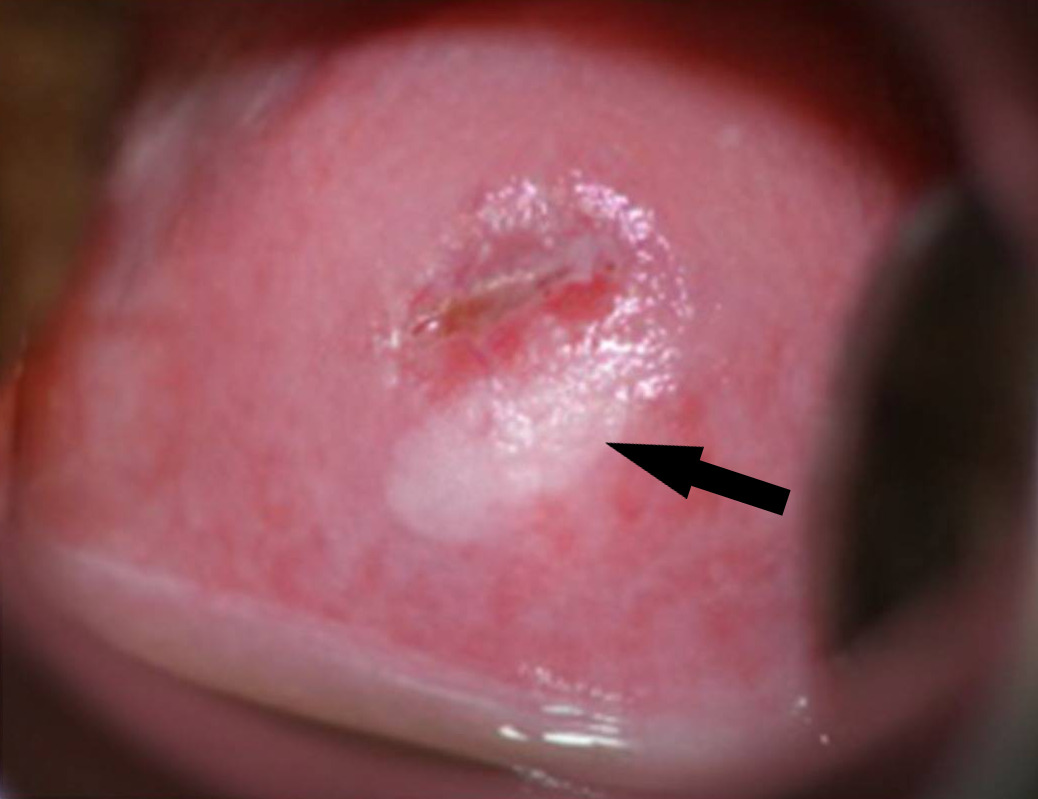

SIL of the cervix on colposcopy:

ovoid SIL located in the 4-to-8-o’clock area of the cervix (arrow). The area is highlighted by the application of acetic acid, which turns the area white. This lesion is then called an acetowhite lesion. Note that the superior edge of the lesion is at the border of the deeper-pink–colored endocervical glandular area (the transformation zone). The small exocervical os indicates that the woman has not had a vaginal birth.

Invasive SCC of the cervix, which has been mostly effaced so that it is barely recognizable: Note the vascularity and the apparent friability of the tumor.

Image: “Population-level scale-up of cervical cancer prevention services in a low-resource setting: development, implementation, and evaluation of the cervical cancer prevention program in Zambia” by Parham GP, Mwanahamuntu MH, Kapambwe S, Muwonge R, Bateman AC, Blevins M, Chibwesha CJ, Pfaendler KS, Mudenda V, Shibemba AL, Chisele S, Mkumba G, Vwalika B, Hicks ML, Vermund SH, Chi BH, Stringer JS, Sankaranarayanan R, Sahasrabuddhe VV. License: CC BY 4.0, edited by Lecturio.| Tumor Tumor Inflammation (T) stage | Description |

|---|---|

| TX | Primary tumor Tumor Inflammation cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of tumor Tumor Inflammation |

| T1 | Confined to the

uterus

Uterus

The uterus, cervix, and fallopian tubes are part of the internal female reproductive system. The uterus has a thick wall made of smooth muscle (the myometrium) and an inner mucosal layer (the endometrium). The most inferior portion of the uterus is the cervix, which connects the uterine cavity to the vagina.

Uterus, Cervix, and Fallopian Tubes: Anatomy

|

| T2 | Invading beyond the

uterus

Uterus

The uterus, cervix, and fallopian tubes are part of the internal female reproductive system. The uterus has a thick wall made of smooth muscle (the myometrium) and an inner mucosal layer (the endometrium). The most inferior portion of the uterus is the cervix, which connects the uterine cavity to the vagina.

Uterus, Cervix, and Fallopian Tubes: Anatomy but not to the pelvic wall or lower 3rd of the

vagina

Vagina

The vagina is the female genital canal, extending from the vulva externally to the cervix uteri internally. The structures have sexual, reproductive, and urinary functions and a rich blood supply, mainly arising from the internal iliac artery.

Vagina, Vulva, and Pelvic Floor: Anatomy

|

| T3 T3 A T3 thyroid hormone normally synthesized and secreted by the thyroid gland in much smaller quantities than thyroxine (T4). Most T3 is derived from peripheral monodeiodination of T4 at the 5′ position of the outer ring of the iodothyronine nucleus. The hormone finally delivered and used by the tissues is mainly t3. Thyroid Hormones |

Extension

Extension

Examination of the Upper Limbs into the pelvic wall or lower 3rd of the

vagina

Vagina

The vagina is the female genital canal, extending from the vulva externally to the cervix uteri internally. The structures have sexual, reproductive, and urinary functions and a rich blood supply, mainly arising from the internal iliac artery.

Vagina, Vulva, and Pelvic Floor: Anatomy or causing

hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis is dilation of the renal collecting system as a result of the obstruction of urine outflow. Hydronephrosis can be unilateral or bilateral. Nephrolithiasis is the most common cause of hydronephrosis in young adults, while prostatic hyperplasia and neoplasm are seen in older patients.

Hydronephrosis

|

| T4 T4 The major hormone derived from the thyroid gland. Thyroxine is synthesized via the iodination of tyrosines (monoiodotyrosine) and the coupling of iodotyrosines (diiodotyrosine) in the thyroglobulin. Thyroxine is released from thyroglobulin by proteolysis and secreted into the blood. Thyroxine is peripherally deiodinated to form triiodothyronine which exerts a broad spectrum of stimulatory effects on cell metabolism. Thyroid Hormones | Invasion of the bladder Bladder A musculomembranous sac along the urinary tract. Urine flows from the kidneys into the bladder via the ureters, and is held there until urination. Pyelonephritis and Perinephric Abscess or rectum Rectum The rectum and anal canal are the most terminal parts of the lower GI tract/large intestine that form a functional unit and control defecation. Fecal continence is maintained by several important anatomic structures including rectal folds, anal valves, the sling-like puborectalis muscle, and internal and external anal sphincters. Rectum and Anal Canal: Anatomy or extends beyond the pelvis Pelvis The pelvis consists of the bony pelvic girdle, the muscular and ligamentous pelvic floor, and the pelvic cavity, which contains viscera, vessels, and multiple nerves and muscles. The pelvic girdle, composed of 2 “hip” bones and the sacrum, is a ring-like bony structure of the axial skeleton that links the vertebral column with the lower extremities. Pelvis: Anatomy |

| Node (N) stage | Description |

|---|---|

| NX | Cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No lymph Lymph The interstitial fluid that is in the lymphatic system. Secondary Lymphatic Organs node metastasis Metastasis The transfer of a neoplasm from one organ or part of the body to another remote from the primary site. Grading, Staging, and Metastasis |

| N0(i+) | Isolated cancer cells in lymph nodes Lymph Nodes They are oval or bean shaped bodies (1 – 30 mm in diameter) located along the lymphatic system. Lymphatic Drainage System: Anatomy (≤ 0.2 mm) |

| N1 | Lymph Lymph The interstitial fluid that is in the lymphatic system. Secondary Lymphatic Organs node metastasis Metastasis The transfer of a neoplasm from one organ or part of the body to another remote from the primary site. Grading, Staging, and Metastasis |

| Metastasis Metastasis The transfer of a neoplasm from one organ or part of the body to another remote from the primary site. Grading, Staging, and Metastasis (M) stage | Description |

|---|---|

| M0 | No distant metastasis Metastasis The transfer of a neoplasm from one organ or part of the body to another remote from the primary site. Grading, Staging, and Metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis Metastasis The transfer of a neoplasm from one organ or part of the body to another remote from the primary site. Grading, Staging, and Metastasis |

The TNM stage can then be used to determine the prognostic stage group.

| Prognostic stage group | Tumor Tumor Inflammation (T) stage | Metastasis Metastasis The transfer of a neoplasm from one organ or part of the body to another remote from the primary site. Grading, Staging, and Metastasis (M) stage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | IA | T1a | M0 |

| IB | T1b | M0 | |

| II | IIA | T2a | M0 |

| IIB | T2b | M0 | |

| III | IIIA | T3a | M0 |

| IIIB | T3b | M0 | |

| IV | IVA | T4 T4 The major hormone derived from the thyroid gland. Thyroxine is synthesized via the iodination of tyrosines (monoiodotyrosine) and the coupling of iodotyrosines (diiodotyrosine) in the thyroglobulin. Thyroxine is released from thyroglobulin by proteolysis and secreted into the blood. Thyroxine is peripherally deiodinated to form triiodothyronine which exerts a broad spectrum of stimulatory effects on cell metabolism. Thyroid Hormones | M0 |

| IVB | Any | M1 | |

Management depends on the stage, extension Extension Examination of the Upper Limbs to nearby lymph nodes Lymph Nodes They are oval or bean shaped bodies (1 – 30 mm in diameter) located along the lymphatic system. Lymphatic Drainage System: Anatomy and tissue, and the patient’s age, pregnancy Pregnancy The status during which female mammals carry their developing young (embryos or fetuses) in utero before birth, beginning from fertilization to birth. Pregnancy: Diagnosis, Physiology, and Care status, and desire to maintain fertility.