Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is visual impairment due to changes in the macula Macula An oval area in the retina, 3 to 5 mm in diameter, usually located temporal to the posterior pole of the eye and slightly below the level of the optic disk. It is characterized by the presence of a yellow pigment diffusely permeating the inner layers, contains the fovea centralis in its center, and provides the best phototropic visual acuity. It is devoid of retinal blood vessels, except in its periphery, and receives nourishment from the choriocapillaris of the choroid. Eye: Anatomy, the area responsible for high-acuity vision Vision Ophthalmic Exam. It is marked by central vision Vision Ophthalmic Exam loss with peripheral vision Vision Ophthalmic Exam relatively spared. Risk factors include advanced age, smoking Smoking Willful or deliberate act of inhaling and exhaling smoke from burning substances or agents held by hand. Interstitial Lung Diseases, family history Family History Adult Health Maintenance, and cardiovascular disease. The 2 types of AMD are exudative (wet) or non-exudative (dry). The difference between these 2 types is the presence of choroidal neovascularization in wet AMD, which manifests as visual distortion Distortion Defense Mechanisms or loss. The more frequently occurring dry AMD is usually asymptomatic but in a minority of cases leads to vision Vision Ophthalmic Exam loss. There is no treatment for early dry AMD but Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS 2) supplements are recommended for advanced disease. Inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor Vascular endothelial growth factor A family of angiogenic proteins that are closely-related to vascular endothelial growth factor a. They play an important role in the growth and differentiation of vascular as well as lymphatic endothelial cells. Wound Healing are used for wet AMD.

Last updated: May 17, 2024

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD):

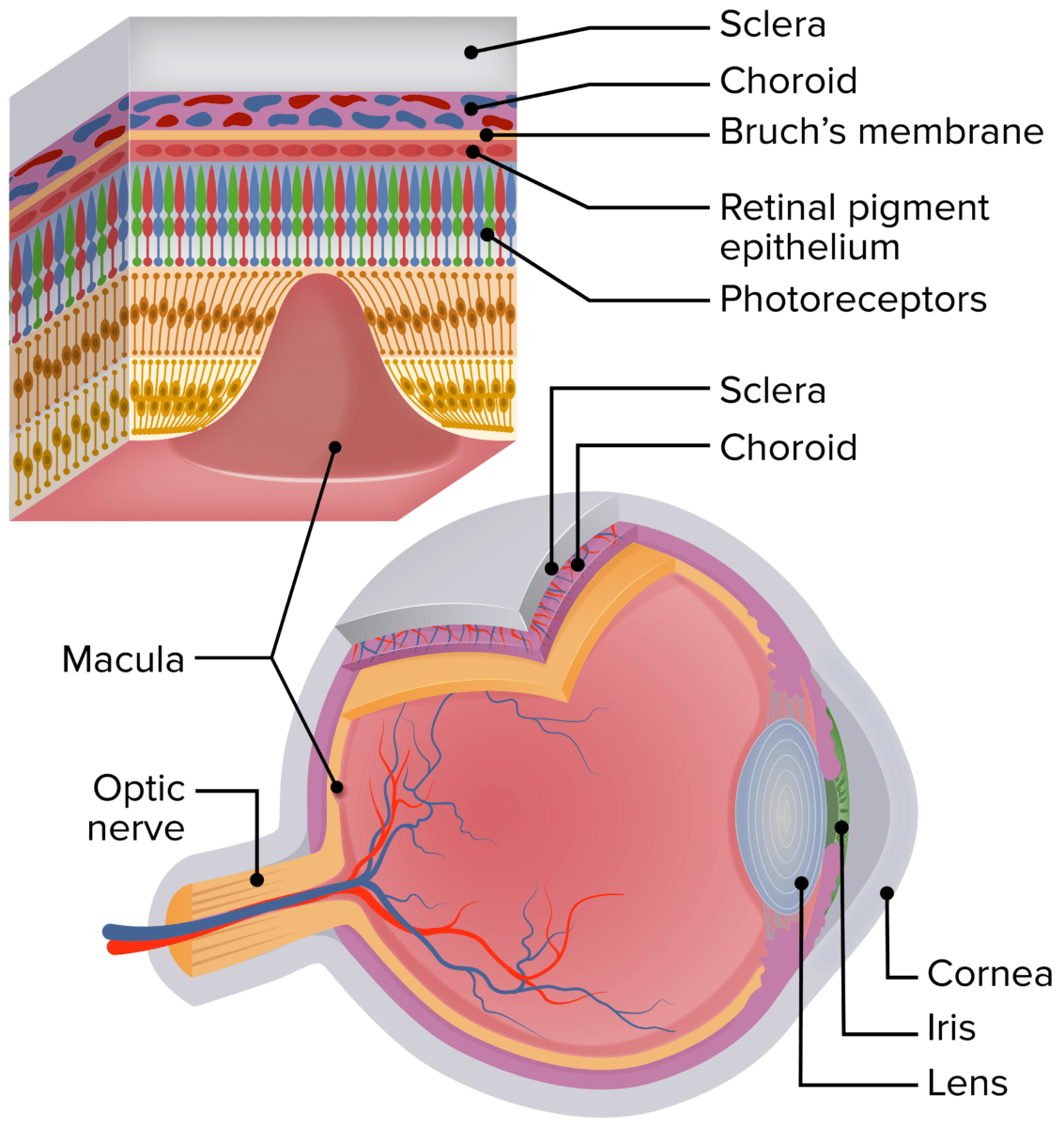

A schematic of the human eye showing the location of the macula. The enlarged section of the retina shows the retinal layers and the relationship of the photoreceptors with the RPE, Bruch’s membrane, and the choriocapillaris.

Image by Lecturio.

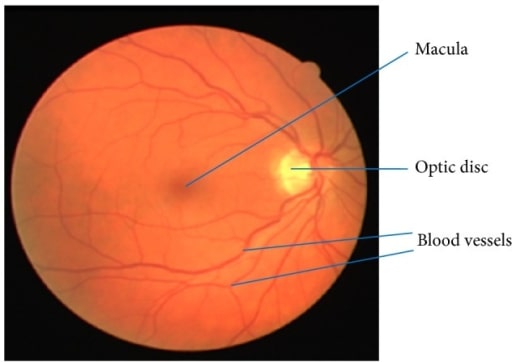

Retinal image showing the macula, blood vessels, and optic disc

Image: “Retinal image showing blood vessels and OD” by Department of ECE, SACS MAVMM Engineering College, Madurai, Tamil Nadu 625 301, India. License: CC BY 3.0

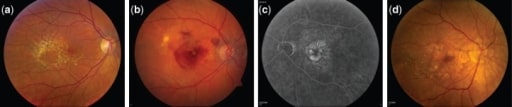

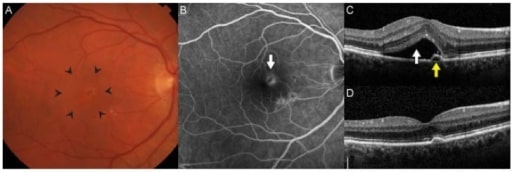

Fundus photographs showing different stages of AMD progression.

(a) Large and intermediate drusen at intermediate stage of AMD

(b) Neovascular AMD: right eye with subretinal fluid, hemorrhage, and hard exudate in the presence of choroidal neovascularization

(c) Fluorescein angiography of the neovascular AMD: left eye showing hyperfluorescence of the fluorescein angiogram corresponding to the area of the choroidal neovascularization

(d) Central geographic atrophy: right eye with evidence of geographic atrophy involving the center of the fovea with evidence of large drusen temporally

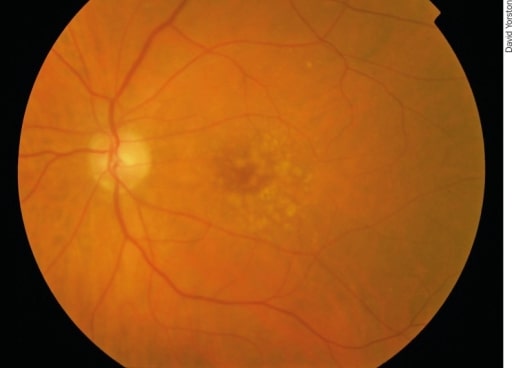

Early AMD: There are irregular pale dots at the macula, which are called drusen. They are caused by a build-up of waste products from photoreceptor metabolism. Although drusen are associated with AMD, most patients with drusen will not develop severe AMD.

Image: “Early AMD” by Africa Regional Medical Advisor: Fred Hollows Foundation, Kigali, Rwanda. License: CC BY 2.0

Drusen are yellow deposits under the retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye. Drusen consist of lipids and fatty protein.

Image: “Oxidative stress, innate immunity, and age-related macular degeneration” by Department of Ophthalmology and Shiley Eye Institute, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA. License: CC BY 4.0

Example of normal vision

Image: “An example of normal vision” by National Eye Institute. License: Public Domain

Vision affected by AMD

Image: “The same view with age-related macular degeneration” by National Eye Institute. License: Public Domain

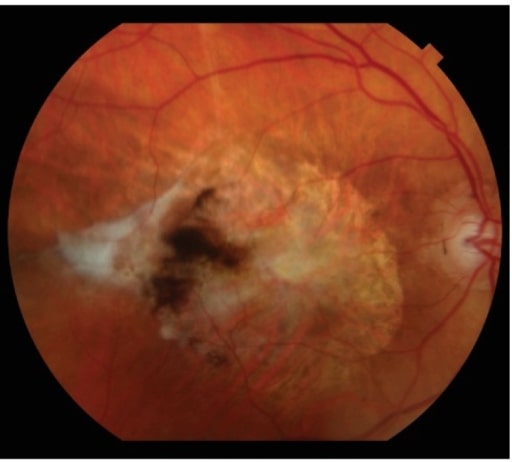

Subretinal fibrotic scarring is the end-stage manifestation of neovascular AMD.

Image: “Subretinal fibrotic scarring” by Retina Service, Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA. License: CC BY 4.0

Neovascular AMD can also present with significant retinal hemorrhage.

Image: “Neovascular age-related macular degeneration” by Retina Service, Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA. License: CC BY 4.0

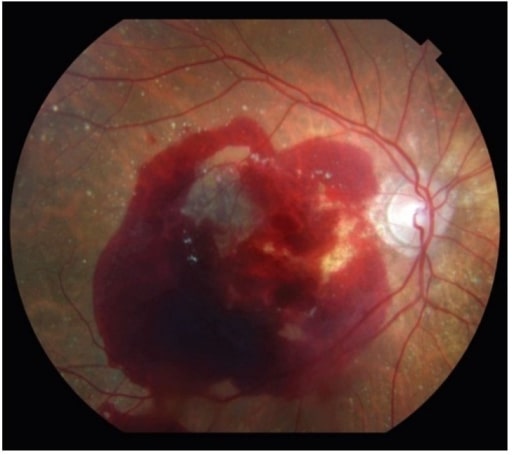

1. Amsler grid: normal vision (left); 2. Amsler grid: AMD with metamorphopsia (right). Note the distorted lines.

Image: “Amsler Grid” by Africa Regional Medical Advisor: Fred Hollows Foundation, Kigali, Rwanda. License: CC BY 2.0

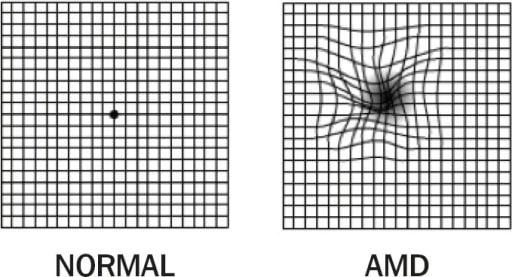

Choroidal neovascularization is the hallmark of neovascular AMD. (A): There is often thickening or elevation of the retina seen clinically through stereoscopic biomicroscopy (area within arrowheads). (B): On fluorescein angiography, neovascular membranes appear as hyperfluorescent lesions deep in the retina (arrow) that leak over time. (C): Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography allows for detailed cross-sectional imaging of retinal anatomy. In this patient, there was subretinal fluid (white arrow) and a small adjacent pigment epithelial detachment. Visual acuity was 20/32. (D): After 3 monthly intravitreal injections of ranibizumab, the fluid resolved, and visual acuity improved to 20/20.

Image: “Age-Related Macular Degeneration” by Retina Service, Department of Ophthalmology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA. License: CC BY 4.0