Endometriosis is a common disease in which patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship have endometrial tissue implanted outside of the uterus Uterus The uterus, cervix, and fallopian tubes are part of the internal female reproductive system. The uterus has a thick wall made of smooth muscle (the myometrium) and an inner mucosal layer (the endometrium). The most inferior portion of the uterus is the cervix, which connects the uterine cavity to the vagina. Uterus, Cervix, and Fallopian Tubes: Anatomy. Endometrial implants can occur anywhere in the pelvis Pelvis The pelvis consists of the bony pelvic girdle, the muscular and ligamentous pelvic floor, and the pelvic cavity, which contains viscera, vessels, and multiple nerves and muscles. The pelvic girdle, composed of 2 "hip" bones and the sacrum, is a ring-like bony structure of the axial skeleton that links the vertebral column with the lower extremities. Pelvis: Anatomy, including the ovaries Ovaries Ovaries are the paired gonads of the female reproductive system that contain haploid gametes known as oocytes. The ovaries are located intraperitoneally in the pelvis, just posterior to the broad ligament, and are connected to the pelvic sidewall and to the uterus by ligaments. These organs function to secrete hormones (estrogen and progesterone) and to produce the female germ cells (oocytes). Ovaries: Anatomy, the broad and uterosacral ligaments Uterosacral ligaments Vagina, Vulva, and Pelvic Floor: Anatomy, the pelvic peritoneum Peritoneum The peritoneum is a serous membrane lining the abdominopelvic cavity. This lining is formed by connective tissue and originates from the mesoderm. The membrane lines both the abdominal walls (as parietal peritoneum) and all of the visceral organs (as visceral peritoneum). Peritoneum: Anatomy, and the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts. Implants outside of the abdominopelvic cavity are also possible, though uncommon. Endometriosis typically presents in a reproductive-aged female with pelvic pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways that worsens around menstruation Menstruation The periodic shedding of the endometrium and associated menstrual bleeding in the menstrual cycle of humans and primates. Menstruation is due to the decline in circulating progesterone, and occurs at the late luteal phase when luteolysis of the corpus luteum takes place. Menstrual Cycle. Endometrial implants tend to be inflammatory, leading to cyclic, chronic pain Chronic pain Aching sensation that persists for more than a few months. It may or may not be associated with trauma or disease, and may persist after the initial injury has healed. Its localization, character, and timing are more vague than with acute pain. Pain Management; adhesions; and an increased risk of infertility Infertility Infertility is the inability to conceive in the context of regular intercourse. The most common causes of infertility in women are related to ovulatory dysfunction or tubal obstruction, whereas, in men, abnormal sperm is a common cause. Infertility. The diagnosis is usually made clinically, though definitive diagnosis requires laparoscopy Laparoscopy Laparoscopy is surgical exploration and interventions performed through small incisions with a camera and long instruments. Laparotomy and Laparoscopy. Lab work is rarely useful. Management involves suppression Suppression Defense Mechanisms of endometrial growth with progestins Progestins Compounds that interact with progesterone receptors in target tissues to bring about the effects similar to those of progesterone. Primary actions of progestins, including natural and synthetic steroids, are on the uterus and the mammary gland in preparation for and in maintenance of pregnancy. Hormonal Contraceptives, typically with oral contraceptive Oral contraceptive Compounds, usually hormonal, taken orally in order to block ovulation and prevent the occurrence of pregnancy. The hormones are generally estrogen or progesterone or both. Benign Liver Tumors pills. In severe cases, surgery is helpful to confirm the diagnosis and treat any implants.

Last updated: Apr 14, 2025

Endometriosis is a condition in which endometrial glands and stroma implant outside of the uterus Uterus The uterus, cervix, and fallopian tubes are part of the internal female reproductive system. The uterus has a thick wall made of smooth muscle (the myometrium) and an inner mucosal layer (the endometrium). The most inferior portion of the uterus is the cervix, which connects the uterine cavity to the vagina. Uterus, Cervix, and Fallopian Tubes: Anatomy. These implants can be highly inflammatory but are generally not malignant.

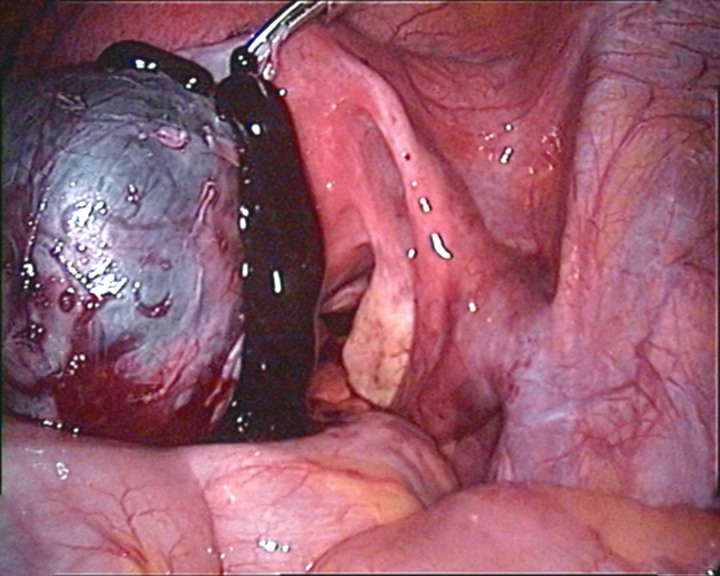

Perforated endometrioma: ectopic endometrial tissue implanted on or within the ovary. These masses are benign and called endometriomas, or chocolate cysts.

Image: “Perforierte Endometriosezyste” by Hic et nunc. License: Public DomainDefinitive diagnosis can only be made on histologic examination of a surgical biopsy Biopsy Removal and pathologic examination of specimens from the living body. Ewing Sarcoma. The diagnosis is therefore often made clinically based on history and exam findings alone, unless imaging suggests an endometrioma.

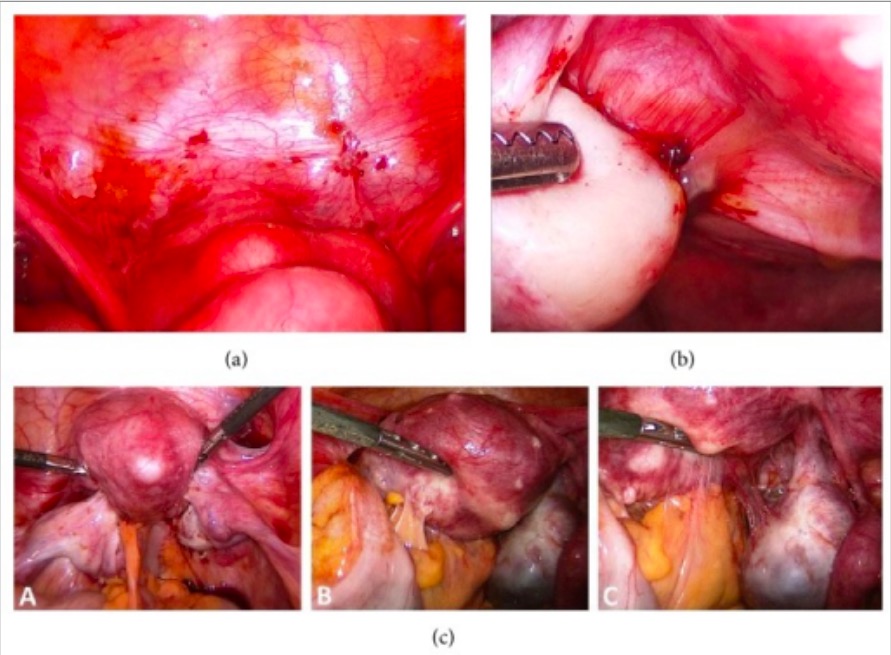

Findings suggestive of endometriosis:

Endometrial lesions and pelvic adhesions seen on laparoscopy

Image: “Endoscopic image of endometriosis” by Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Clinics of Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel, Arnold-Heller-Straße 3/24, 24105 Kiel, Germany. License: CC BY 3.0The following are used in patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship who cannot take or derive no benefit from 1st-line management:

The goal is to provide a definitive histologic diagnosis and resect any visible lesions to treat pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways.