Rickettsiae are a diverse collection of obligate intracellular, gram-negative bacteria gram-negative bacteria Bacteria which lose crystal violet stain but are stained pink when treated by gram's method. Bacteriology that have a tropism for vascular endothelial cells. The vectors for transmission vary by species but include ticks Ticks Blood-sucking acarid parasites of the order ixodida comprising two families: the softbacked ticks (argasidae) and hardbacked ticks (ixodidae). Ticks are larger than their relatives, the mites. They penetrate the skin of their host by means of highly specialized, hooked mouth parts and feed on its blood. Ticks attack all groups of terrestrial vertebrates. In humans they are responsible for many tick-borne diseases, including the transmission of rocky mountain spotted fever; tularemia; babesiosis; african swine fever; and relapsing fever. Coxiella/Q Fever, fleas, mites Mites Any arthropod of the subclass acari except the ticks. They are minute animals related to the spiders, usually having transparent or semitransparent bodies. They may be parasitic on humans and domestic animals, producing various irritations of the skin (mite infestations). Many mite species are important to human and veterinary medicine as both parasite and vector. Mites also infest plants. Scabies, and lice. The most clinically relevant pathogens are R. rickettsii, which causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever; R. prowazekii, which causes epidemic (louse-borne) typhus; R. typhi, which causes endemic typhus; and R. akari, which causes rickettsialpox. All of these diseases are a form of inflammatory vasculitis Vasculitis Inflammation of any one of the blood vessels, including the arteries; veins; and rest of the vasculature system in the body. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and commonly present with fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever, headache Headache The symptom of pain in the cranial region. It may be an isolated benign occurrence or manifestation of a wide variety of headache disorders. Brain Abscess, and rash Rash Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. Treatment is with doxycycline.

Last updated: Jun 27, 2025

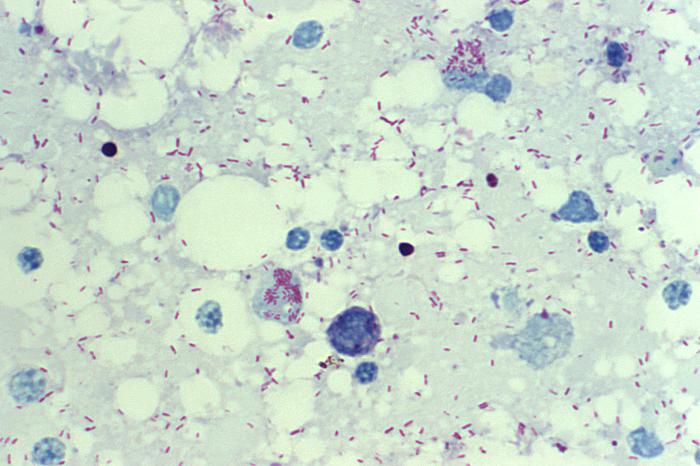

R. rickettsii: photomicrograph of a yolk sac smear, showing many intracellular bacteria stained in red by Giemsa stain

Image: “10955” by CDC/ Billie Ruth Bird. License: Public Domain

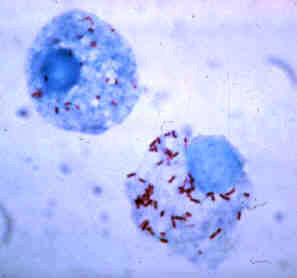

Giemsa-stained R. rickettsii in the cells of a tick

Image: “Rickettsia rickettsii” by CDC. License: Public Domain| R. rickettsii | R. prowazekii | R. typhi | R. akari | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vector | Hard ticks Ticks Blood-sucking acarid parasites of the order ixodida comprising two families: the softbacked ticks (argasidae) and hardbacked ticks (ixodidae). Ticks are larger than their relatives, the mites. They penetrate the skin of their host by means of highly specialized, hooked mouth parts and feed on its blood. Ticks attack all groups of terrestrial vertebrates. In humans they are responsible for many tick-borne diseases, including the transmission of rocky mountain spotted fever; tularemia; babesiosis; african swine fever; and relapsing fever. Coxiella/Q Fever (Ixodidae family): Dermacentor (dog tick), Amblyoma (wood tick) | Human lice (

Pediculus humanus corporis

Pediculus Humanus Corporis

Epidemic Typhus):

|

Rat and cat flea bites | Mites Mites Any arthropod of the subclass acari except the ticks. They are minute animals related to the spiders, usually having transparent or semitransparent bodies. They may be parasitic on humans and domestic animals, producing various irritations of the skin (mite infestations). Many mite species are important to human and veterinary medicine as both parasite and vector. Mites also infest plants. Scabies from mice |

| Disease | Rocky Mountain spotted fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever (the most serious rickettsial disease) | Epidemic (louse-borne) typhus | Endemic typhus | Rickettsialpox (the least serious rickettsial disease) |

| Geographic variations |

|

|

|

|

Epidemiology:

Pathophysiology:

Clinical presentation:

Prognosis Prognosis A prediction of the probable outcome of a disease based on a individual’s condition and the usual course of the disease as seen in similar situations. Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas:

Identification Identification Defense Mechanisms:

Characteristic spotted rash of Rocky Mountain spotted fever: hand and wrist of an affected child

Image: “Rocky Mountain spotted fever PHIL 1962 lores” by CDC. License: Public DomainEpidemic (louse-borne) typhus is now a rare disease.

Pathogenesis:

Clinical presentation:

Brill-Zinsser disease Brill-Zinsser Disease Epidemic Typhus:

Rash in a patient with epidemic typhus

Image: “Epidemic typhus Burundi” by D. Raoult, V. Roux, J.B. Ndihokubwayo, G. Bise, D. Baudon, G. Martet, and R. Birtles. License: Public Domain

Painless, black, crusted eschar of rickettsialpox, which develops as the last stage of the typical rash (macules → papules → vesicles → crusts/eschars that heal without scarring).

Image: “Rickettsialpox lesion” by Krusell A, Comer JA, Sexton DJ. License: Public Domain