Brucellosis (also known as undulant fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever, Mediterranean fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever, or Malta fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever) is a zoonotic infection that spreads predominantly through ingestion of unpasteurized dairy products or direct contact with infected animal products. Clinical manifestations include fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever, arthralgias, malaise Malaise Tick-borne Encephalitis Virus, lymphadenopathy Lymphadenopathy Lymphadenopathy is lymph node enlargement (> 1 cm) and is benign and self-limited in most patients. Etiologies include malignancy, infection, and autoimmune disorders, as well as iatrogenic causes such as the use of certain medications. Generalized lymphadenopathy often indicates underlying systemic disease. Lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly Hepatosplenomegaly Cytomegalovirus. The clinical manifestations, exposure history, serology Serology The study of serum, especially of antigen-antibody reactions in vitro. Yellow Fever Virus, and culture data are used in the diagnosis. Treatment involves a combination of antibiotics, including doxycycline, rifampin Rifampin A semisynthetic antibiotic produced from streptomyces mediterranei. It has a broad antibacterial spectrum, including activity against several forms of Mycobacterium. In susceptible organisms it inhibits dna-dependent RNA polymerase activity by forming a stable complex with the enzyme. It thus suppresses the initiation of RNA synthesis. Rifampin is bactericidal, and acts on both intracellular and extracellular organisms. Epiglottitis, and aminoglycosides Aminoglycosides Aminoglycosides are a class of antibiotics including gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin, neomycin, plazomicin, and streptomycin. The class binds the 30S ribosomal subunit to inhibit bacterial protein synthesis. Unlike other medications with a similar mechanism of action, aminoglycosides are bactericidal. Aminoglycosides. Preventative measures include avoiding unpasteurized dairy products, vaccinating livestock, and using caution around animals Animals Unicellular or multicellular, heterotrophic organisms, that have sensation and the power of voluntary movement. Under the older five kingdom paradigm, animalia was one of the kingdoms. Under the modern three domain model, animalia represents one of the many groups in the domain eukaryota. Cell Types: Eukaryotic versus Prokaryotic.

Last updated: Nov 7, 2022

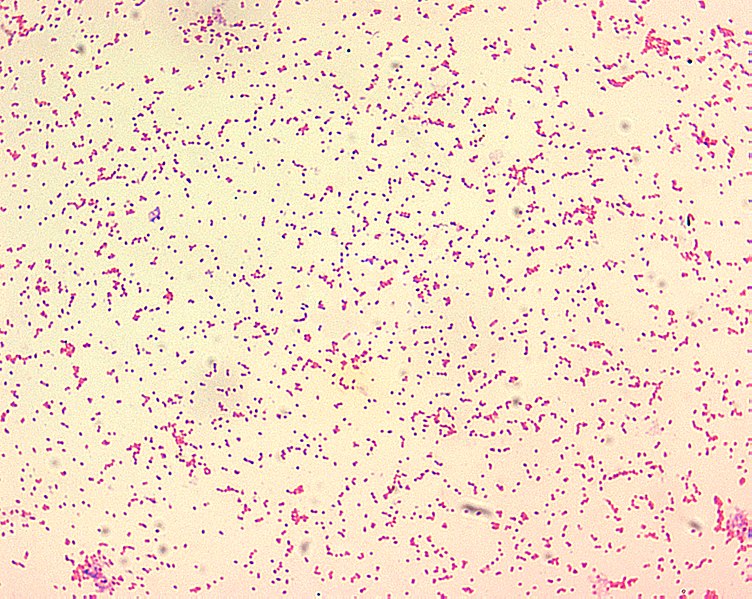

Brucellae are poorly staining, gram-negative coccobacilli. They are mostly seen as tiny, single cells that look like “fine sand.”

Image: “Brucella spp” by CDC. License: Public DomainRelapse Relapse Relapsing Fever can occur in 4%–24% of patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship, usually within 1 year.

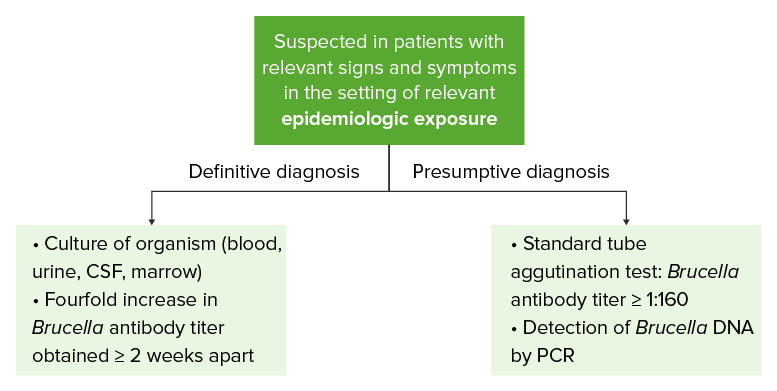

As this diagram illustrates, testing modalities that provide a definitive diagnosis usually require a considerable amount of time. While waiting for the results of these modalities, other testing measures can be used to provide a presumptive diagnosis.

CSF: cerebrospinal fluid

PCR: polymerase chain reaction

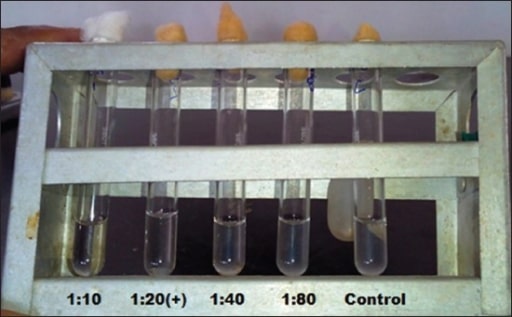

Serum tube agglutination testing is used to detect antibodies to a Borrelia antigen.

From left to right:

Tubes 1 and 2 = positive reaction

Tubes 3 and 4 = negative reaction

Tube 5 = control

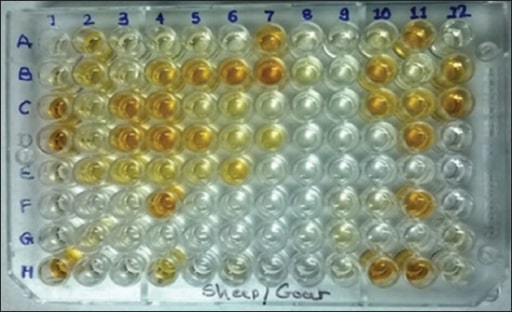

An example of an ELISA test: This test relies on antibody-enzyme complexes to create a color change. Positive tests will be a darker color.

Image: “Microtiter plate” by Department of Veterinary Medicine, Livestock Research Station, Sardarkrushinagar Dantiwada Agricultural University, Sardarkrushinagar, Dantiwada, Gujarat, India. License: CC BY 2.0

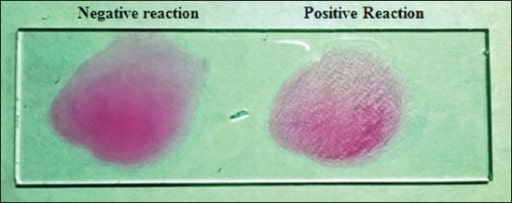

Rose Bengal agglutination test: This test uses a suspension of B. abortus antigens with a pink dye. It will agglutinate with a patient sample if antibodies are present.

Image: “Rose Bengal plate test” by Department of Veterinary Medicine, Livestock Research Station, Sardarkrushinagar Dantiwada Agricultural University, Sardarkrushinagar, Dantiwada, Gujarat, India. License: CC BY 2.0The testing performed is guided by the patient’s clinical presentation and any concerns for complications.

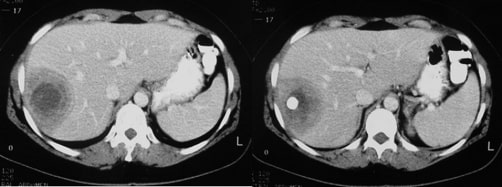

A liver abscess is seen on contrast CT in a patient with brucellosis.

Image: “CT scan” by Diagnostic Radiology Department, Interbalcan Medical Center, Thessaloniki, 55236, Greece. License: CC BY 3.0

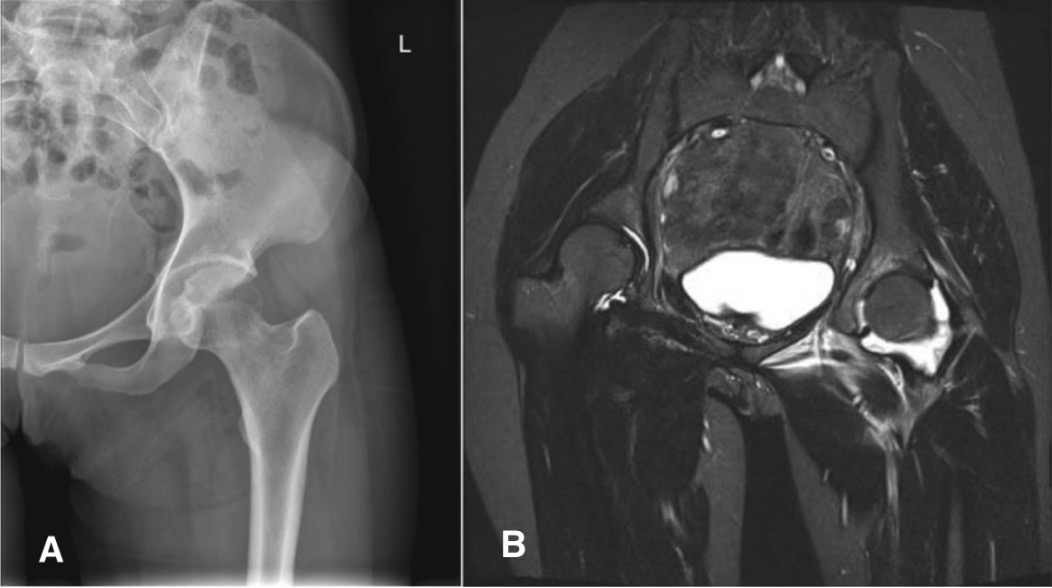

A patient diagnosed with septic arthritis caused by Brucella melitensis:

(A) normal X-ray of the left hip

(B) T2–weighted MRI coronal plane of the pelvis showing marked effusion over the left hip joint

A transthoracic echocardiogram performed on a patient with brucellosis: The white arrows point to the thickened aortic valves. This thickening is secondary to vegetations.

Image: “Transthoracic echocardiogram” by Faculty of Nursing, University of Peloponnese, Orthias Artemidos & Plataion, 23100 Sparta, Greece. License: CC BY 3.0, edited by Lecturio.| Organism | Brucella | Haemophilus Haemophilus Haemophilus is a genus of Gram-negative coccobacilli, all of whose strains require at least 1 of 2 factors for growth (factor V [NAD] and factor X [heme]); therefore, it is most often isolated on chocolate agar, which can supply both factors. The pathogenic species are H. influenzae and H. ducreyi. Haemophilus | Bordetella Bordetella Bordetella is a genus of obligate aerobic, Gram-negative coccobacilli. They are highly fastidious and difficult to isolate. The most important pathologic species is Bordetella pertussis (B. pertussis), which is commonly isolated on Bordet-Gengou agar. Bordetella |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinically relevant species |

|

|

|

| Microbiology features |

|

|

|

| Virulence factors Virulence factors Those components of an organism that determine its capacity to cause disease but are not required for its viability per se. Two classes have been characterized: toxins, biological and surface adhesion molecules that affect the ability of the microorganism to invade and colonize a host. Haemophilus |

|

|

|

| Reservoir Reservoir Animate or inanimate sources which normally harbor disease-causing organisms and thus serve as potential sources of disease outbreaks. Reservoirs are distinguished from vectors (disease vectors) and carriers, which are agents of disease transmission rather than continuing sources of potential disease outbreaks. Humans may serve both as disease reservoirs and carriers. Escherichia coli |

|

Humans | Humans |

| Transmission | Contact with animal products |

|

Respiratory droplets Droplets Varicella-Zoster Virus/Chickenpox |

| Clinical presentation |

|

|

Pertussis Pertussis Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a potentially life-threatening highly contagious bacterial infection of the respiratory tract caused by Bordetella pertussis. The disease has 3 clinical stages, the second and third of which are characterized by an intense paroxysmal cough, an inspiratory whoop, and post-tussive vomiting. Pertussis (Whooping Cough) |

| Diagnosis |

|

Culture |

|

| Management |

|

|

|

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

FHA: filamentous hemagglutinin

IgA: immunoglobulin A

LPS: lipopolysaccharide

PCR: polymerase chain reaction

SAT: serum tube agglutination test

TMP-SMX: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole