The embryological development of craniofacial structures is an intricate sequential Sequential Computed Tomography (CT) process involving tissue growth and directed cell apoptosis Apoptosis A regulated cell death mechanism characterized by distinctive morphologic changes in the nucleus and cytoplasm, including the endonucleolytic cleavage of genomic DNA, at regularly spaced, internucleosomal sites, I.e., DNA fragmentation. It is genetically-programmed and serves as a balance to mitosis in regulating the size of animal tissues and in mediating pathologic processes associated with tumor growth. Ischemic Cell Damage. Disruption of any step in this process may result in the formation of a cleft lip alone or in combination with a cleft palate Palate The palate is the structure that forms the roof of the mouth and floor of the nasal cavity. This structure is divided into soft and hard palates. Palate: Anatomy. As the most common craniofacial malformation of the newborn Newborn An infant during the first 28 days after birth. Physical Examination of the Newborn, the diagnosis of a cleft is clinical and usually apparent at birth. The type and severity of the defect cause various degrees of difficulty with speech development, feeding, swallowing Swallowing The act of taking solids and liquids into the gastrointestinal tract through the mouth and throat. Gastrointestinal Motility, tooth eruption, and cosmetic issues. Ultimate correction is through surgical repair.

Last updated: Jun 21, 2025

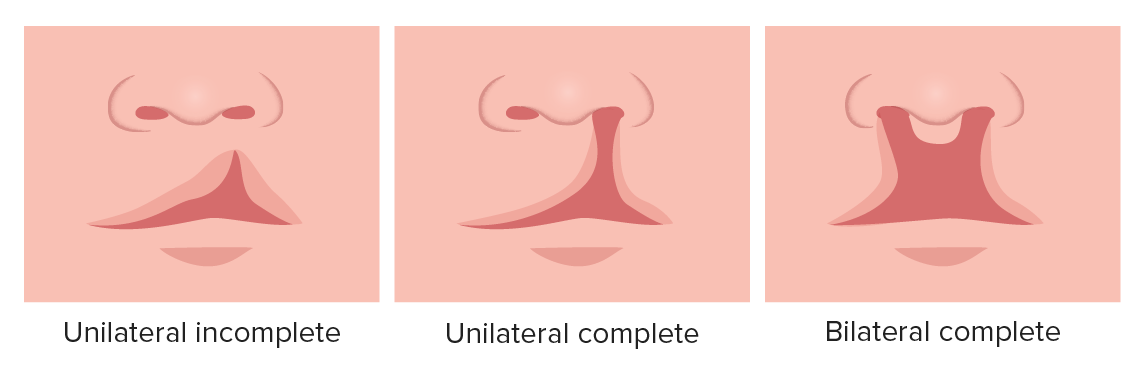

Cleft lip

Image by Lecturio.

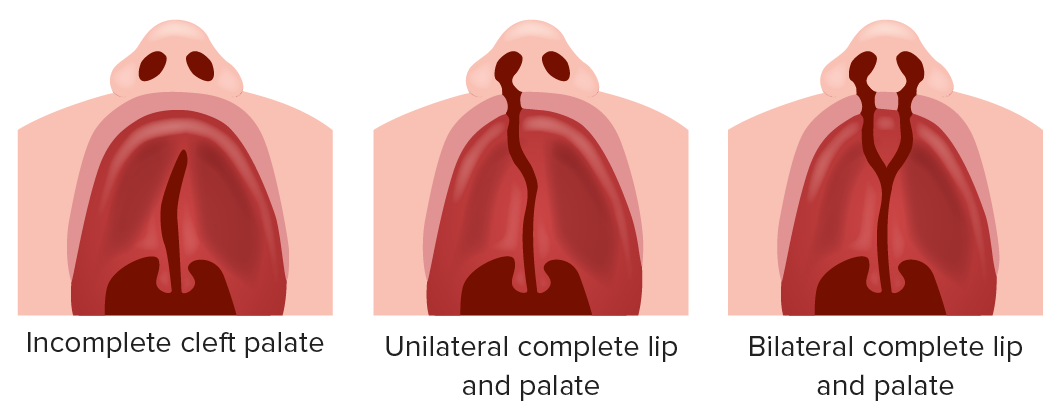

Cleft palate

Image by Lecturio.The prevalence Prevalence The total number of cases of a given disease in a specified population at a designated time. It is differentiated from incidence, which refers to the number of new cases in the population at a given time. Measures of Disease Frequency of orofacial clefts varies widely around the world. The following data are specific to the United States.

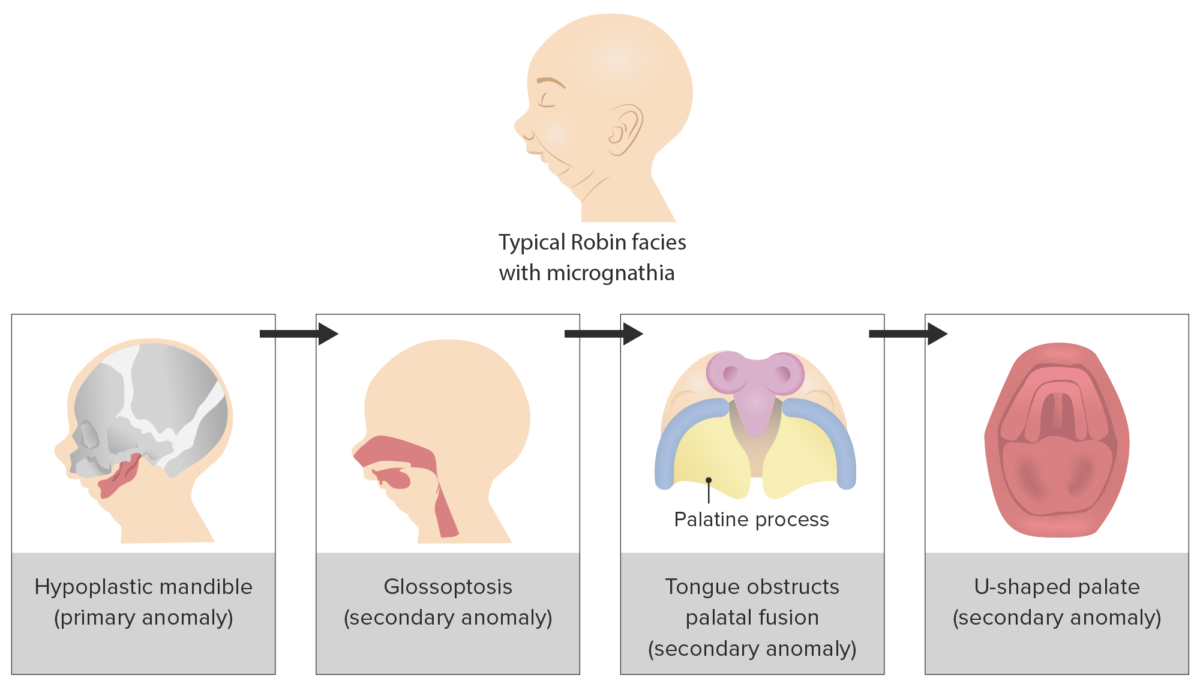

Progression of triad of events that underlies the clinical presentation of Pierre Robin sequence

Image by Lecturio.

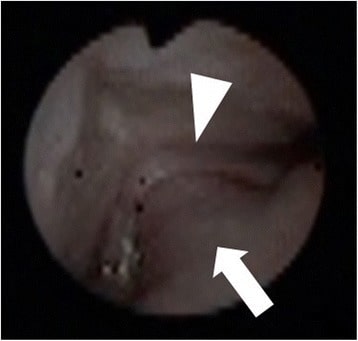

Imaging finding of the oral cavity during fiberoptic intubation in cases of Pierre Robin sequence. Cleft palate (triangle): root of the tongue (arrowhead). The tongue protruding into the nasal cavity via a cleft palate results in airway obstruction (larynx is not visible).

Image: “Pierre Robin sequence with upper airway obstruction” by US National Library of Medicine. License: CC BY 4.0

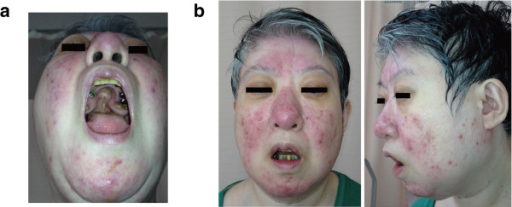

22q11.2 deletion features in a 48-year-old woman.

(a): The patient’s cleft palate had previous surgery.

(b): Mild dysmorphic facial features, including a low anterior hairline, swollen eyelids, malar flatness, nose with a bulbous nasal tip, hypoplastic nasal alae, square and flat nasal root, small mouth, and a thin upper lip.

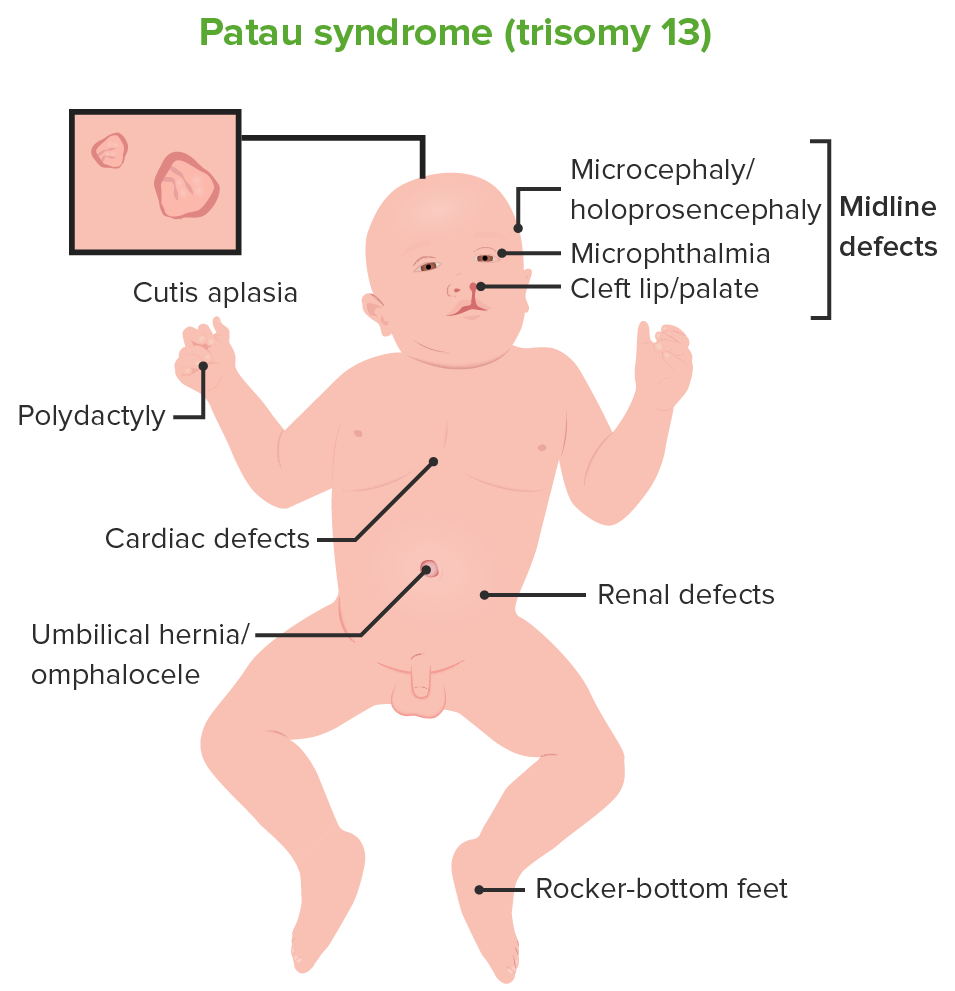

Patau syndrome (trisomy 13)

Image by Lecturio.

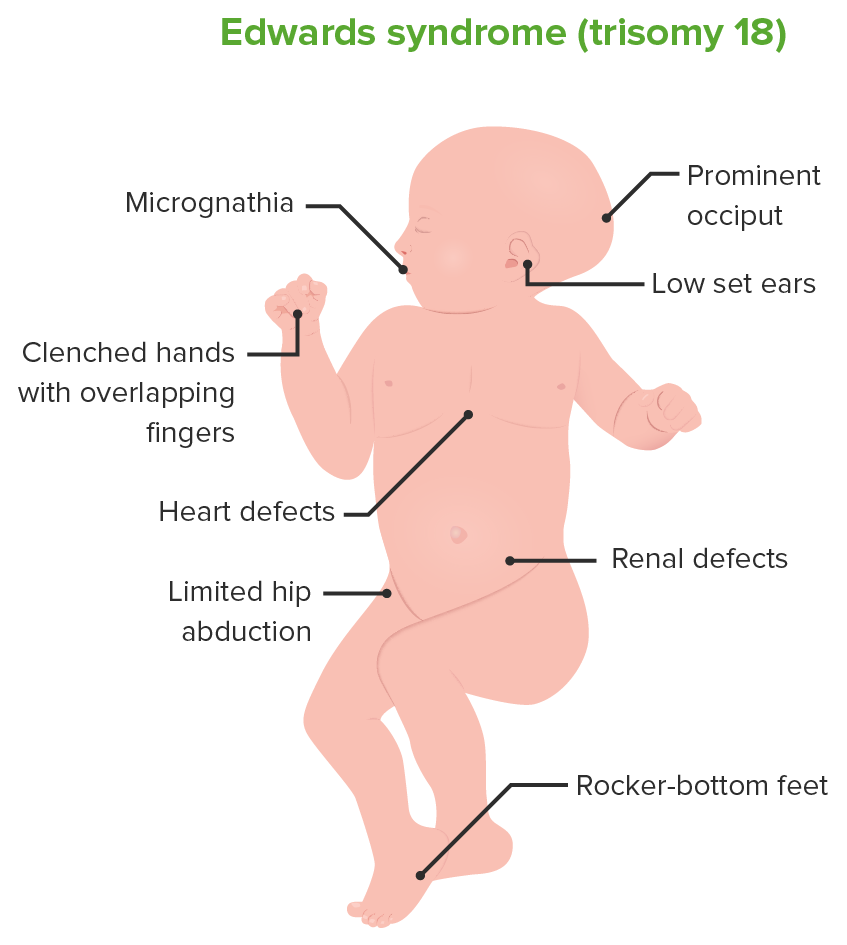

Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18)

Image by Lecturio.All clefts arise from errors in the embryological development of the face.

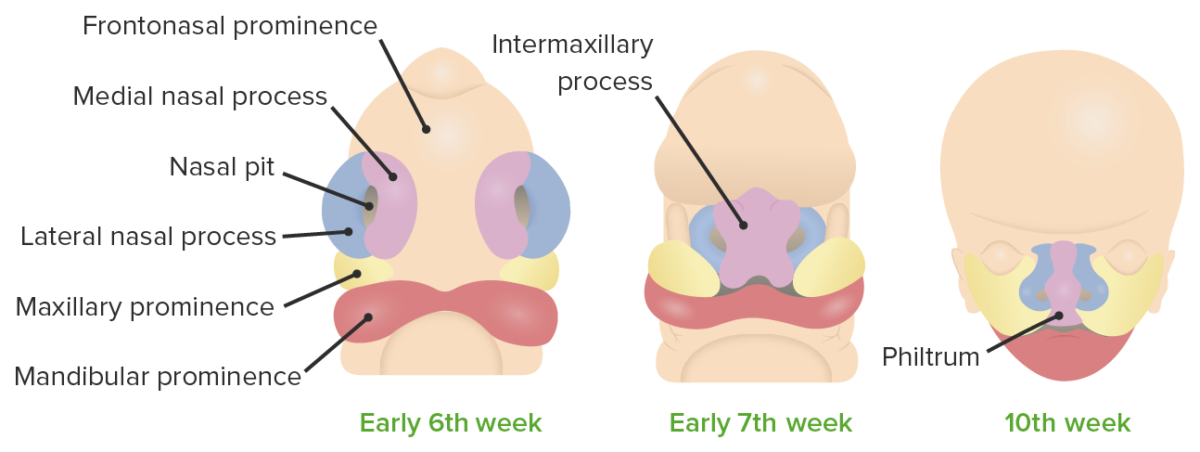

Development of the lip

Image by Lecturio.

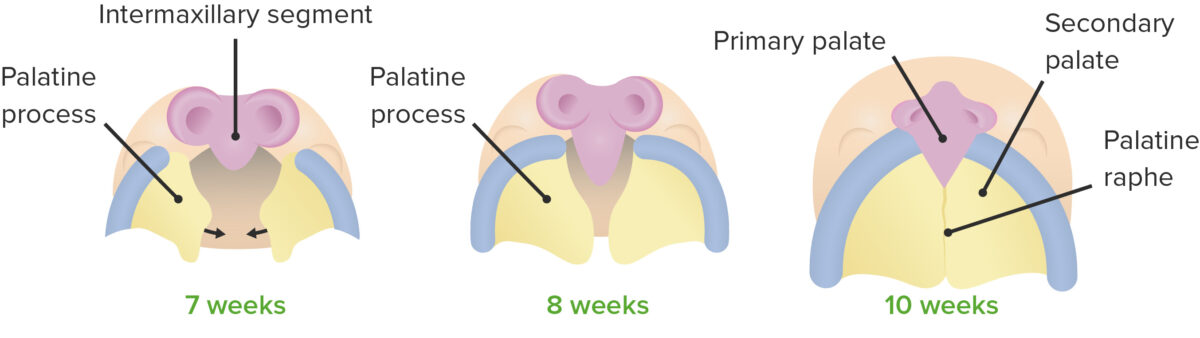

Formation of the palate

Image by Lecturio.

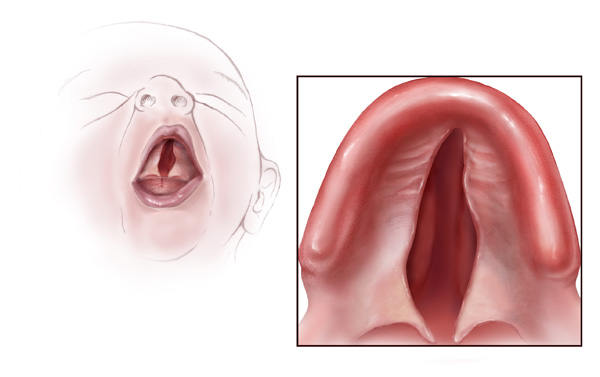

Illustration of a baby with a cleft palate

Image: “Cleft palate” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. License: Public Domain

Six-month-old girl before going into surgery to have her unilateral complete cleft lip repaired

Image: “Child born with cleft palate at 5 months of age” by King97tut. License: Public Domain