Spinal disk herniation Herniation Omphalocele (also known as herniated nucleus Nucleus Within a eukaryotic cell, a membrane-limited body which contains chromosomes and one or more nucleoli (cell nucleolus). The nuclear membrane consists of a double unit-type membrane which is perforated by a number of pores; the outermost membrane is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum. A cell may contain more than one nucleus. The Cell: Organelles pulposus) describes the expulsion of the nucleus Nucleus Within a eukaryotic cell, a membrane-limited body which contains chromosomes and one or more nucleoli (cell nucleolus). The nuclear membrane consists of a double unit-type membrane which is perforated by a number of pores; the outermost membrane is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum. A cell may contain more than one nucleus. The Cell: Organelles pulposus through a perforation Perforation A pathological hole in an organ, blood vessel or other soft part of the body, occurring in the absence of external force. Esophagitis in the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disk. Spinal disk herniation Herniation Omphalocele is an important pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways syndrome with the potential for neurologic impairment and is most commonly caused by degenerative disk disease Disk Disease Examination of the Lower Limbs. Clinical presentation depends on the presence or absence of spinal cord Spinal cord The spinal cord is the major conduction pathway connecting the brain to the body; it is part of the CNS. In cross section, the spinal cord is divided into an H-shaped area of gray matter (consisting of synapsing neuronal cell bodies) and a surrounding area of white matter (consisting of ascending and descending tracts of myelinated axons). Spinal Cord: Anatomy or nerve root compression Compression Blunt Chest Trauma and the downstream neurologic sequelae (e.g., radicular pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways, muscle weakness, sensory deficit Sensory Deficit Anterior Cord Syndrome, reflex deficit). Diagnosis is initially clinical and can be confirmed with diagnostic imaging (e.g., MRI). Management can range from conservative to surgical, depending on the situation.

Last updated: Mar 29, 2023

Spinal disk herniation Herniation Omphalocele is a condition wherein the gelatinous central portion of an intervertebral disk is forced through a weakened portion of the fibrocartilaginous outer part of the disk, often resulting in back pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways and/or nerve root irritation.

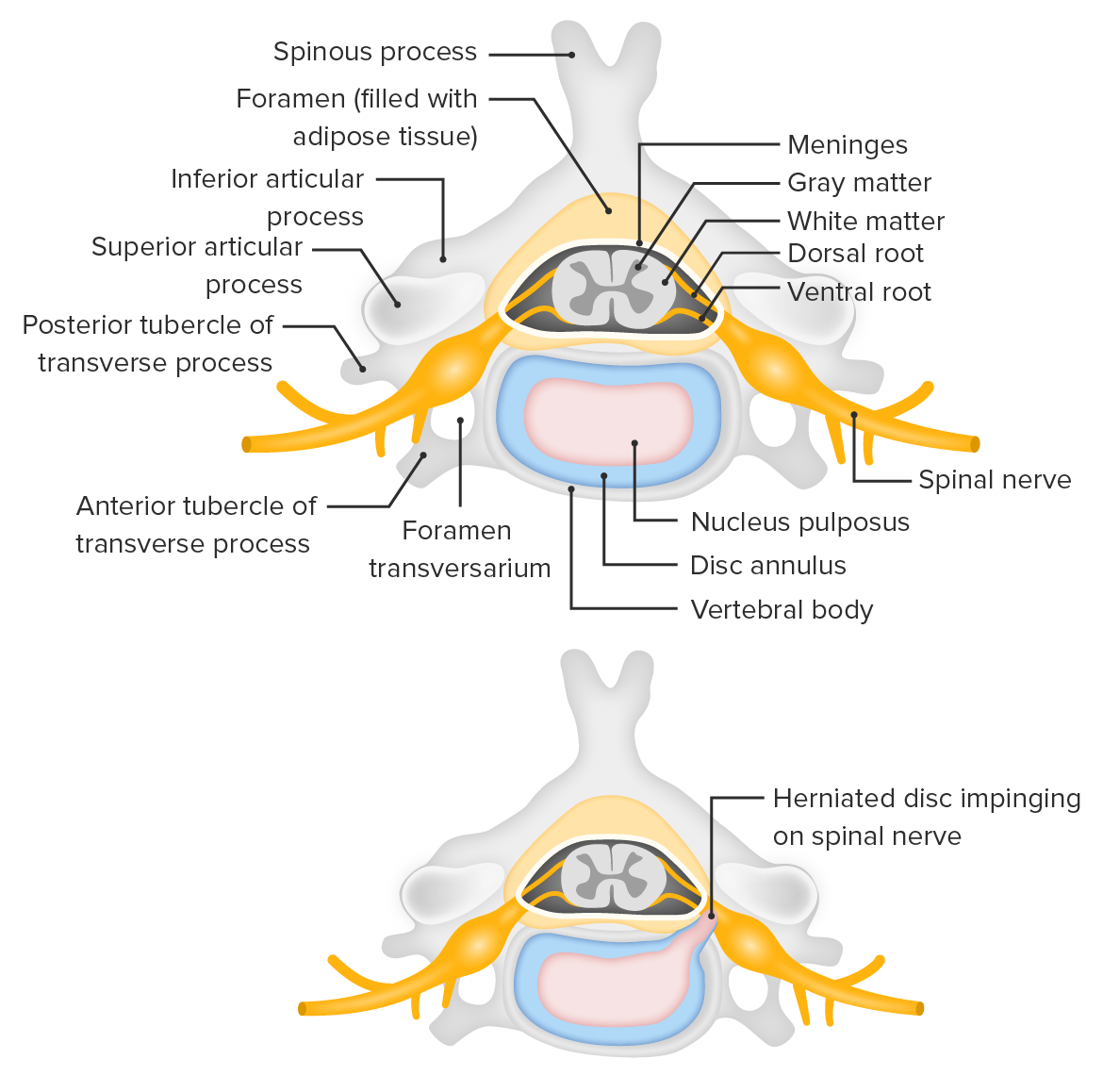

Structure:

Function:

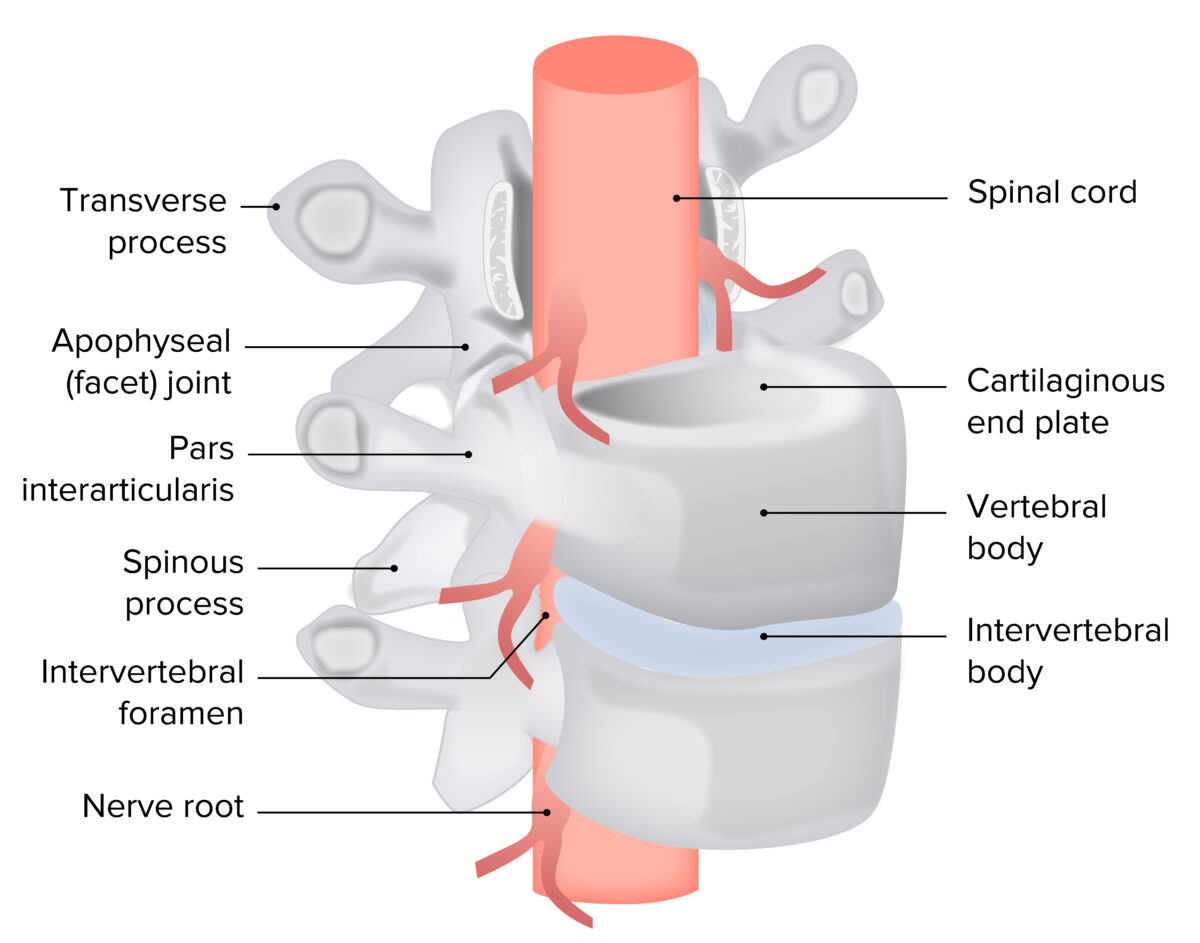

Anatomic relationships:

Anterolateral view of the intervertebral disk complex with neural elements

Image by Lecturio.

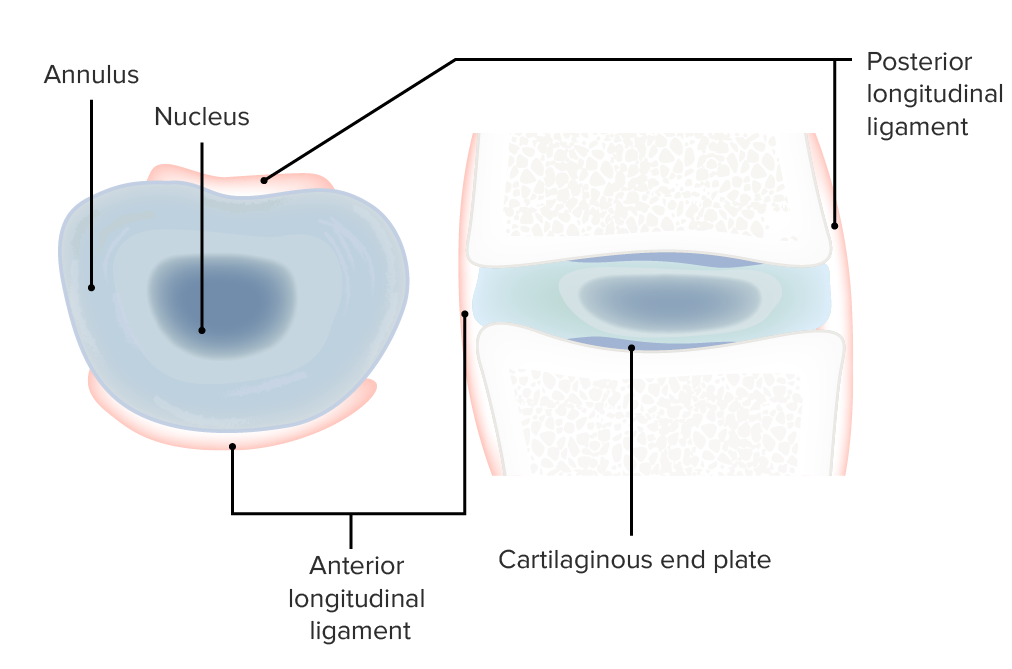

Cross-sectional views of the intervertebral disk complex

Image by Lecturio.

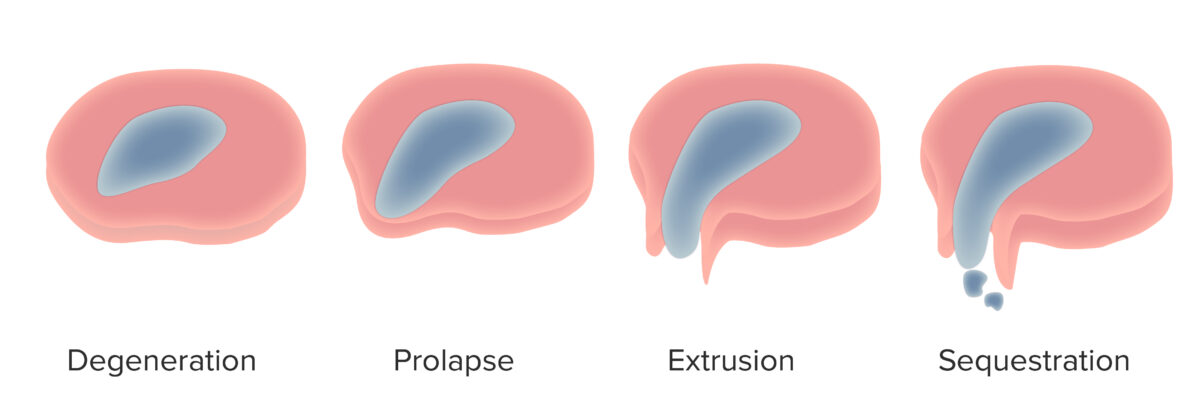

Continuum of spinal disk herniation

Image by Lecturio.

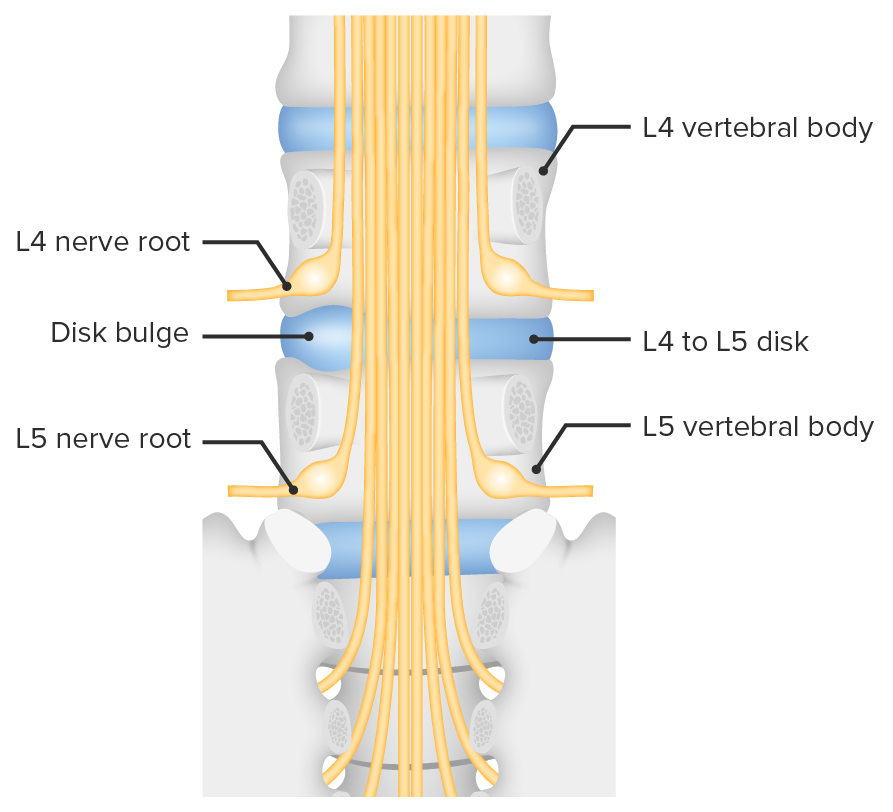

Bulging of the intervertebral disk between L4 and L5, and consequent nerve root compression

Image by Lecturio.

Cross section of the vertebral column showing the herniation of an intervertebral disk compressing a nerve root

Image by Lecturio.Question the individual about the pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways characteristics (e.g., sharp, dull, boring) and accompanying symptoms (e.g., referred pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways, radiating pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways, sensory Sensory Neurons which conduct nerve impulses to the central nervous system. Nervous System: Histology changes, motor Motor Neurons which send impulses peripherally to activate muscles or secretory cells. Nervous System: Histology changes), as well as previous illnesses, which may serve as warning signals for specific causes of pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways with an urgent call for action.

Pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways location and related areas:

Cervical, thoracic, or lumbar pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways in combination with any of the clinical scenarios below are a “red flag” and require early investigation and treatment to prevent significant morbidity Morbidity The proportion of patients with a particular disease during a given year per given unit of population. Measures of Health Status.

| Clinical scenario | Possible diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Severe trauma (due to motor vehicle accidents Motor Vehicle Accidents Spinal Cord Injuries, fall from a great height, and sports injury), and minor trauma in elderly or individuals potentially affected by osteoporosis Osteoporosis Osteoporosis refers to a decrease in bone mass and density leading to an increased number of fractures. There are 2 forms of osteoporosis: primary, which is commonly postmenopausal or senile; and secondary, which is a manifestation of immobilization, underlying medical disorders, or long-term use of certain medications. Osteoporosis; systemic steroid therapy | Vertebral fracture Fracture A fracture is a disruption of the cortex of any bone and periosteum and is commonly due to mechanical stress after an injury or accident. Open fractures due to trauma can be a medical emergency. Fractures are frequently associated with automobile accidents, workplace injuries, and trauma. Overview of Bone Fractures |

| Advanced age, history of tumors, and generalized symptoms ( fatigue Fatigue The state of weariness following a period of exertion, mental or physical, characterized by a decreased capacity for work and reduced efficiency to respond to stimuli. Fibromyalgia, weight loss Weight loss Decrease in existing body weight. Bariatric Surgery, anorexia Anorexia The lack or loss of appetite accompanied by an aversion to food and the inability to eat. It is the defining characteristic of the disorder anorexia nervosa. Anorexia Nervosa), and increased pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways in supine position; severe nocturnal pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways | Tumor Tumor Inflammation |

| Generalized symptoms (acute fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever, chills Chills The sudden sensation of being cold. It may be accompanied by shivering. Fever, loss of appetite, and fatigue Fatigue The state of weariness following a period of exertion, mental or physical, characterized by a decreased capacity for work and reduced efficiency to respond to stimuli. Fibromyalgia), a history of infection and associated general illness; drug use disorder; immune suppression Suppression Defense Mechanisms; strong pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways at night | Infection |

| Pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways radiating into the legs accompanied by paresthesia or weakness; cauda equina syndrome Cauda Equina Syndrome Compressive lesion affecting the nerve roots of the cauda equina (e.g., compression, herniation, inflammation, rupture, or stenosis), which controls the function of the bladder and bowel. Symptoms may include neurological dysfunction of bladder or bowels, loss of sexual sensation and altered sensation or paralysis in the lower extremities. Ankylosing Spondylitis: sudden bladder Bladder A musculomembranous sac along the urinary tract. Urine flows from the kidneys into the bladder via the ureters, and is held there until urination. Pyelonephritis and Perinephric Abscess or rectal dysfunction, perianal and perineal loss of sensation; marked/increasing neurologic deficit; cessation of pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways with increasing paralysis leading to complete loss of function Loss of Function Inflammation of the reference muscle (nerve root death) | Herniated disk |

| Sudden onset of pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways or weakness after lumbar puncture Lumbar Puncture Febrile Infant, intrathecal injection, epidural steroid injection, or spinal anesthesia Spinal anesthesia Procedure in which an anesthetic is injected directly into the spinal cord. Anesthesiology: History and Basic Concepts, especially in individuals taking anticoagulants Anticoagulants Anticoagulants are drugs that retard or interrupt the coagulation cascade. The primary classes of available anticoagulants include heparins, vitamin K-dependent antagonists (e.g., warfarin), direct thrombin inhibitors, and factor Xa inhibitors. Anticoagulants or those with thrombocytopenia Thrombocytopenia Thrombocytopenia occurs when the platelet count is < 150,000 per microliter. The normal range for platelets is usually 150,000-450,000/µL of whole blood. Thrombocytopenia can be a result of decreased production, increased destruction, or splenic sequestration of platelets. Patients are often asymptomatic until platelet counts are < 50,000/µL. Thrombocytopenia or other bleeding dyscrasia | Spinal hematoma Hematoma A collection of blood outside the blood vessels. Hematoma can be localized in an organ, space, or tissue. Intussusception |

Inspection Inspection Dermatologic Examination:

Palpation Palpation Application of fingers with light pressure to the surface of the body to determine consistency of parts beneath in physical diagnosis; includes palpation for determining the outlines of organs. Dermatologic Examination:

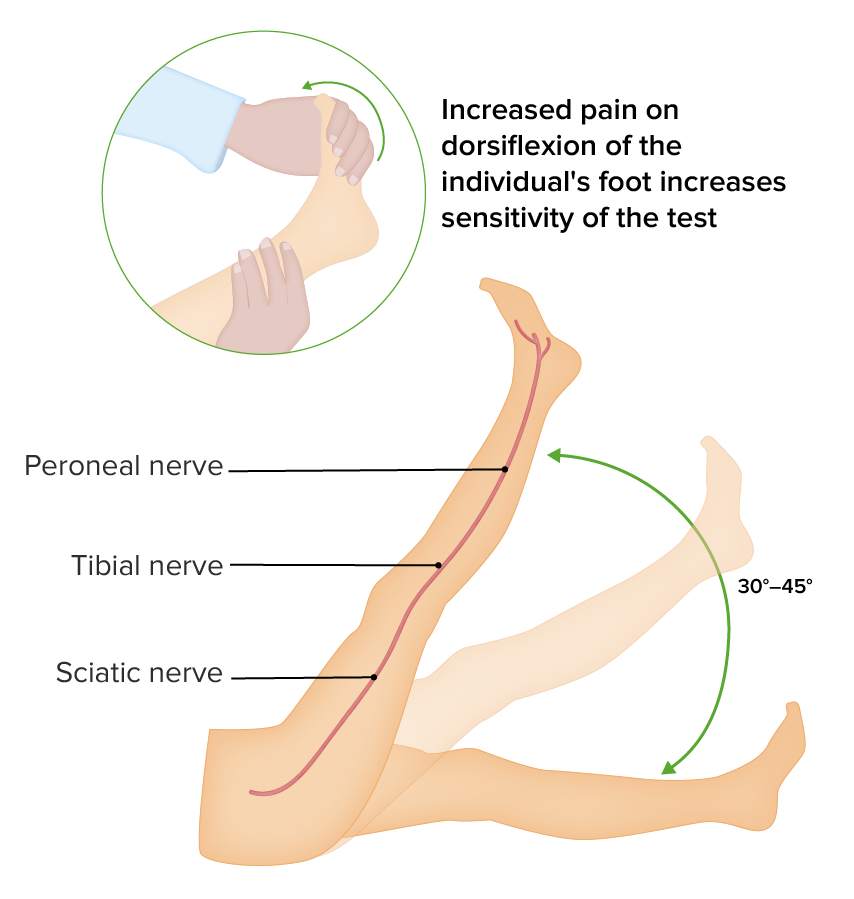

Provocative maneuvers:

Straight leg test (Lasègue test)

Image by Lecturio.Evaluation of radicular symptoms:

| Syndrome | Paresis | Pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways radiation Radiation Emission or propagation of acoustic waves (sound), electromagnetic energy waves (such as light; radio waves; gamma rays; or x-rays), or a stream of subatomic particles (such as electrons; neutrons; protons; or alpha particles). Osteosarcoma, paresthesia, abnormal sensitivity | Weakened reflexes |

|---|---|---|---|

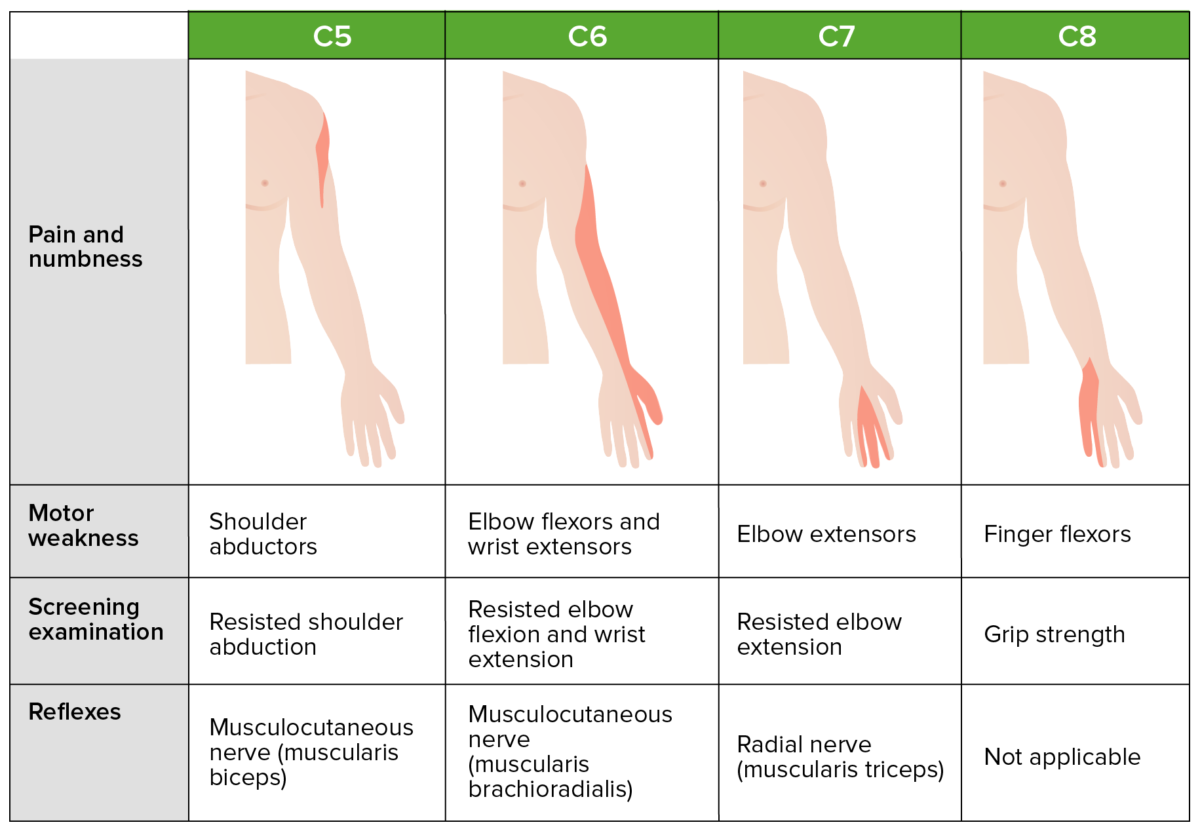

| C5 | Deltoideus | Lateral shoulder | Biceps Biceps Arm: Anatomy reflex |

| C6 | Biceps Biceps Arm: Anatomy brachii, musculus brachioradialis Brachioradialis Forearm: Anatomy | Radial arm Arm The arm, or “upper arm” in common usage, is the region of the upper limb that extends from the shoulder to the elbow joint and connects inferiorly to the forearm through the cubital fossa. It is divided into 2 fascial compartments (anterior and posterior). Arm: Anatomy extending to the thumb | Biceps Biceps Arm: Anatomy reflex, radial reflex |

| C7 | Triceps brachii Triceps brachii Elbow Joint: Anatomy | Regio antebrachii dorsalis, dorsal hand Hand The hand constitutes the distal part of the upper limb and provides the fine, precise movements needed in activities of daily living. It consists of 5 metacarpal bones and 14 phalanges, as well as numerous muscles innervated by the median and ulnar nerves. Hand: Anatomy extending to 2nd–4th fingers | Triceps reflex, biceps Biceps Arm: Anatomy reflex |

| C8 | Small hand Hand The hand constitutes the distal part of the upper limb and provides the fine, precise movements needed in activities of daily living. It consists of 5 metacarpal bones and 14 phalanges, as well as numerous muscles innervated by the median and ulnar nerves. Hand: Anatomy muscles | Ulnar arm Arm The arm, or “upper arm” in common usage, is the region of the upper limb that extends from the shoulder to the elbow joint and connects inferiorly to the forearm through the cubital fossa. It is divided into 2 fascial compartments (anterior and posterior). Arm: Anatomy, lateral hand Hand The hand constitutes the distal part of the upper limb and provides the fine, precise movements needed in activities of daily living. It consists of 5 metacarpal bones and 14 phalanges, as well as numerous muscles innervated by the median and ulnar nerves. Hand: Anatomy extending to 5th finger | Not applicable |

| Syndrome | Paresis | Pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways radiation Radiation Emission or propagation of acoustic waves (sound), electromagnetic energy waves (such as light; radio waves; gamma rays; or x-rays), or a stream of subatomic particles (such as electrons; neutrons; protons; or alpha particles). Osteosarcoma, paresthesia, sensitivity disturbance | Weakened reflexes |

|---|---|---|---|

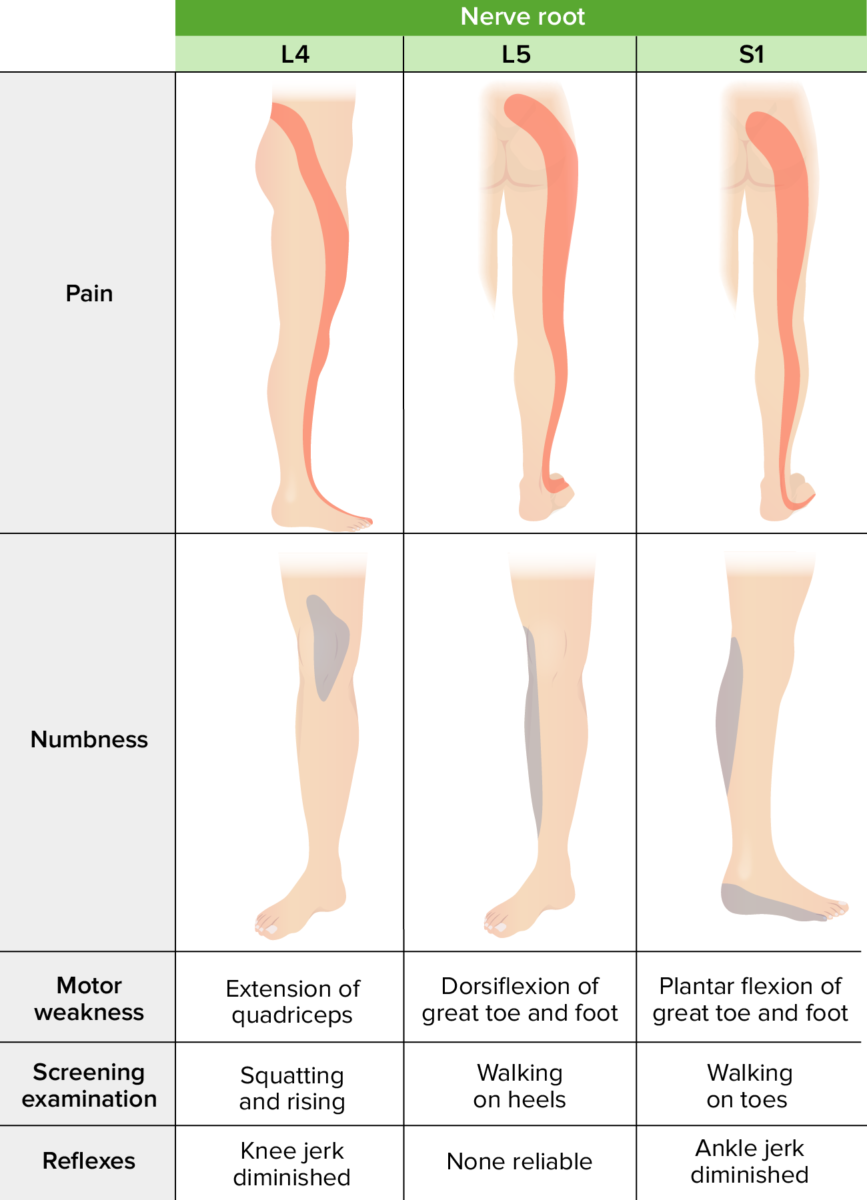

| L3 | Quadriceps, hip adductors, iliopsoas | Transverse anterior aspect of the thigh Thigh The thigh is the region of the lower limb found between the hip and the knee joint. There is a single bone in the thigh called the femur, which is surrounded by large muscles grouped into 3 fascial compartments. Thigh: Anatomy toward the knee | Adductor reflex, perhaps patellar reflex |

| L4 | Quadriceps, musculus tibialis anterior Tibialis anterior Leg: Anatomy | Anterior and medial lower leg Leg The lower leg, or just “leg” in anatomical terms, is the part of the lower limb between the knee and the ankle joint. The bony structure is composed of the tibia and fibula bones, and the muscles of the leg are grouped into the anterior, lateral, and posterior compartments by extensions of fascia. Leg: Anatomy | Patellar reflex |

| L5 | Extensor hallucis longus Extensor hallucis longus Leg: Anatomy (lifts big toe), perhaps musculus tibialis anterior Tibialis anterior Leg: Anatomy and posterior, musculus gluteus medius Gluteus medius Gluteal Region: Anatomy | Lateral and anterior lower leg Leg The lower leg, or just “leg” in anatomical terms, is the part of the lower limb between the knee and the ankle joint. The bony structure is composed of the tibia and fibula bones, and the muscles of the leg are grouped into the anterior, lateral, and posterior compartments by extensions of fascia. Leg: Anatomy, dorsal foot Foot The foot is the terminal portion of the lower limb, whose primary function is to bear weight and facilitate locomotion. The foot comprises 26 bones, including the tarsal bones, metatarsal bones, and phalanges. The bones of the foot form longitudinal and transverse arches and are supported by various muscles, ligaments, and tendons. Foot: Anatomy extending to big toe | Tibialis posterior Tibialis posterior Leg: Anatomy reflex |

| S1 S1 Heart Sounds | Triceps surae (plantar flexion Flexion Examination of the Upper Limbs, test perhaps through standing on toes), musculus gluteus maximus Gluteus maximus Gluteal Region: Anatomy, musculus biceps femoris Biceps femoris Thigh: Anatomy | Posterior and lateral thigh Thigh The thigh is the region of the lower limb found between the hip and the knee joint. There is a single bone in the thigh called the femur, which is surrounded by large muscles grouped into 3 fascial compartments. Thigh: Anatomy, lateral foot Foot The foot is the terminal portion of the lower limb, whose primary function is to bear weight and facilitate locomotion. The foot comprises 26 bones, including the tarsal bones, metatarsal bones, and phalanges. The bones of the foot form longitudinal and transverse arches and are supported by various muscles, ligaments, and tendons. Foot: Anatomy | Achilles reflex Achilles Reflex Examination of the Lower Limbs |

| S2 S2 Heart Sounds– S4 S4 Heart Sounds | Bladder Bladder A musculomembranous sac along the urinary tract. Urine flows from the kidneys into the bladder via the ureters, and is held there until urination. Pyelonephritis and Perinephric Abscess and rectal dysfunction (neurologic emergency, see cauda syndrome) | Posterior thigh Thigh The thigh is the region of the lower limb found between the hip and the knee joint. There is a single bone in the thigh called the femur, which is surrounded by large muscles grouped into 3 fascial compartments. Thigh: Anatomy, anal region (cauda syndrome: breech presentation Breech presentation A malpresentation of the fetus at near term or during obstetric labor with the fetal cephalic pole in the fundus of the uterus. There are three types of breech: the complete breech with flexed hips and knees; the incomplete breech with one or both hips partially or fully extended; the frank breech with flexed hips and extended knees. Fetal Malpresentation and Malposition) | Anal reflex |

Common cervical dermatomes, myotomes, and clinical presentation

Image by Lecturio.

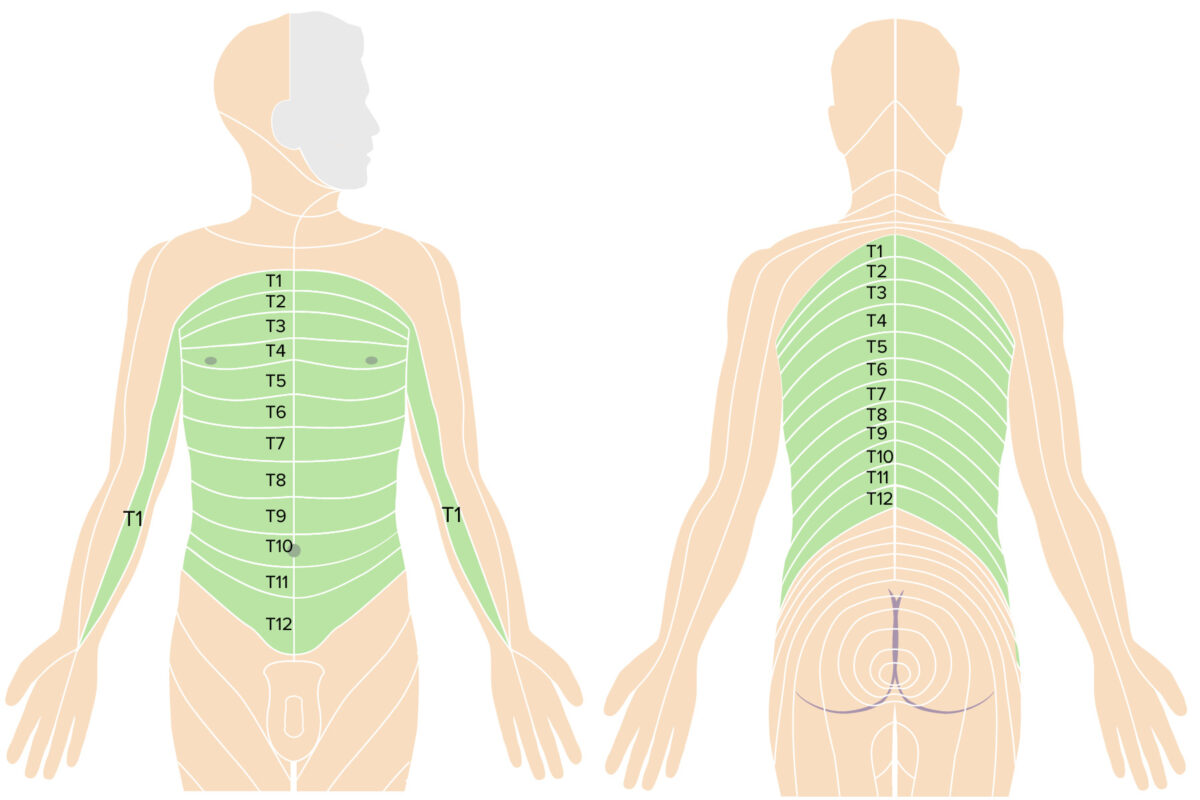

Thoracic dermatomes

Image by Lecturio.

Common lumbosacral dermatomes, myotomes, and clinical presentation

Image by Lecturio.Evaluation of myelopathy:

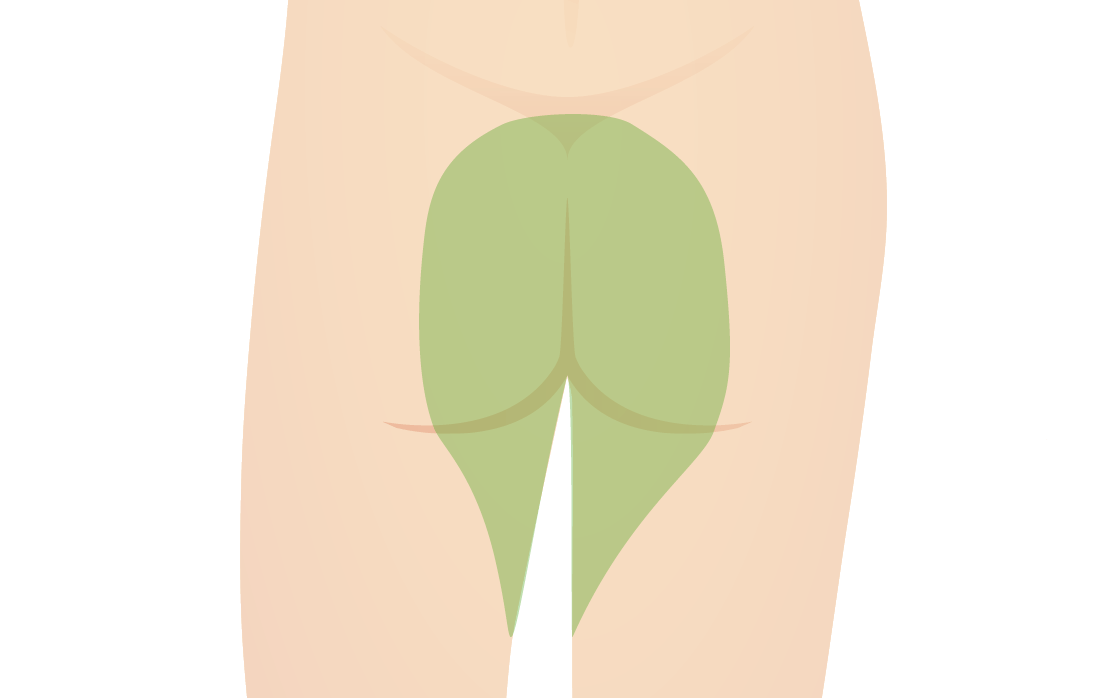

Evaluation of conus medullaris Conus Medullaris Spinal Cord Injuries/ cauda equina Cauda Equina The lower part of the spinal cord consisting of the lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal nerve roots. Spinal Cord Injuries syndromes:

Sensory area affected in “saddle anesthesia”

Image by Lecturio.Diagnosis is usually suspected with a thorough history and physical examination and often confirmed with diagnostic imaging (e.g., MRI).

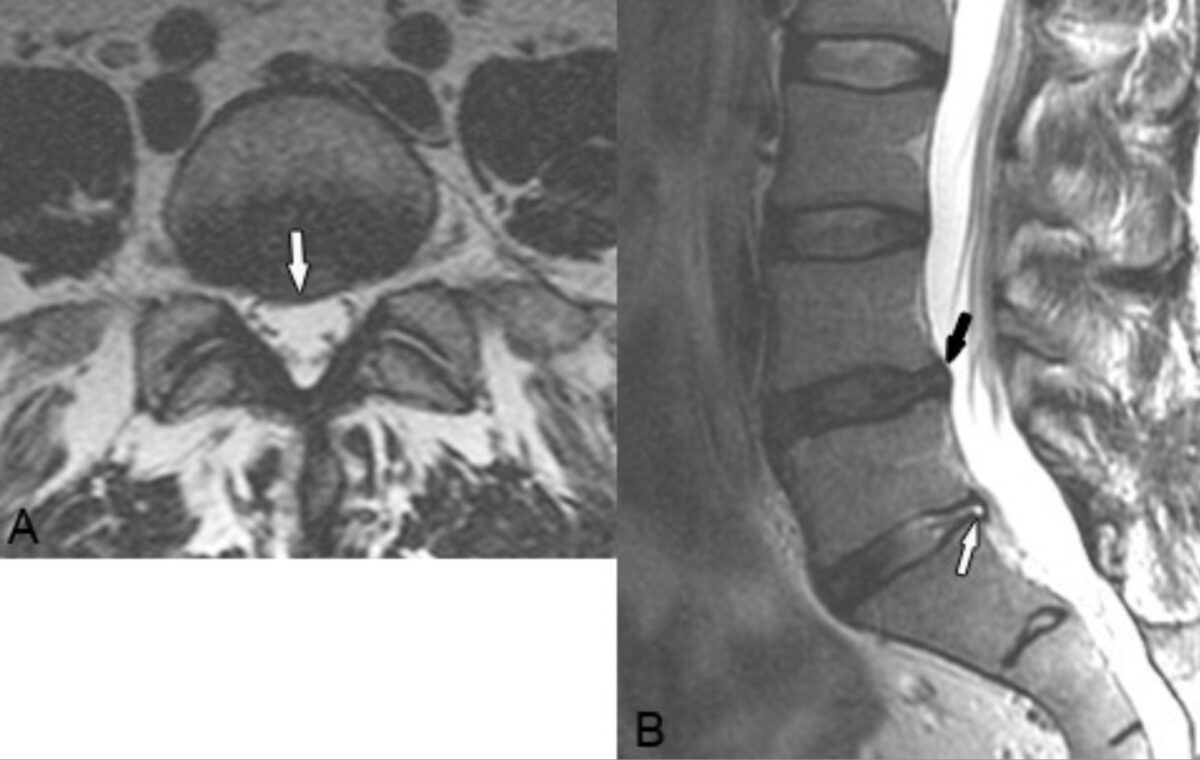

Disk bulge:

Axial (A) and sagittal (B) T2-weighted images reveal a focal right-central disk bulge at L4–L5 that slightly indents the thecal sac and extends into the right nerve root canal (white arrow in A, black arrow in B). A more focal protrusion and associated annular tear is present at L5–S1 (white arrow in B).

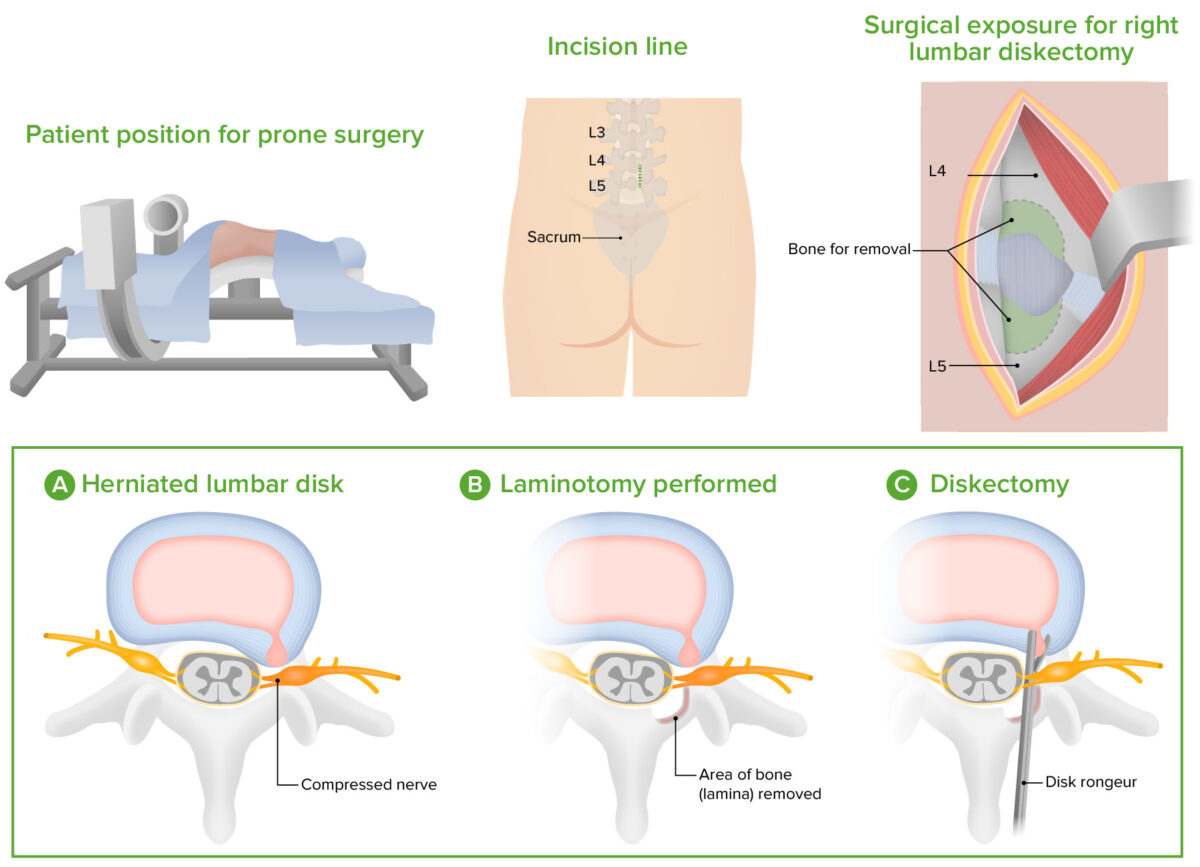

Surgical management is reserved for individuals whose condition does not respond to conservative treatment and/or in whom persistent or rapidly worsening neurologic deficits Neurologic Deficits High-Risk Headaches are present.

Microdiskectomy technique

Image by Lecturio.