Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria. The bacteria usually attack the lungs but can also damage other parts of the body. Approximately 30% of people around the world are infected with this pathogen, with the majority harboring a latent infection. Tuberculosis spreads through the air when a person with active pulmonary infection coughs or sneezes. M. tuberculosis are acid-fast, slowly growing bacteria that can survive in macrophages, allowing for a latent infection that can remain asymptomatic for decades, posing a challenge to diagnosis, therapy, and prevention. The diagnosis is established with tuberculin skin test, sputum culture, and lung imaging. The mainstay of management is anti-mycobacterial drugs.

Last updated: Jun 21, 2025

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease affecting the lungs Lungs Lungs are the main organs of the respiratory system. Lungs are paired viscera located in the thoracic cavity and are composed of spongy tissue. The primary function of the lungs is to oxygenate blood and eliminate CO2. Lungs: Anatomy and, sometimes, other organs. Tuberculosis is caused by Mycobacterium Mycobacterium Mycobacterium is a genus of the family Mycobacteriaceae in the phylum Actinobacteria. Mycobacteria comprise more than 150 species of facultative intracellular bacilli that are mostly obligate aerobes. Mycobacteria are responsible for multiple human infections including serious diseases, such as tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), leprosy (M. leprae), and M. avium complex infections. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) bacteria Bacteria Bacteria are prokaryotic single-celled microorganisms that are metabolically active and divide by binary fission. Some of these organisms play a significant role in the pathogenesis of diseases. Bacteriology.

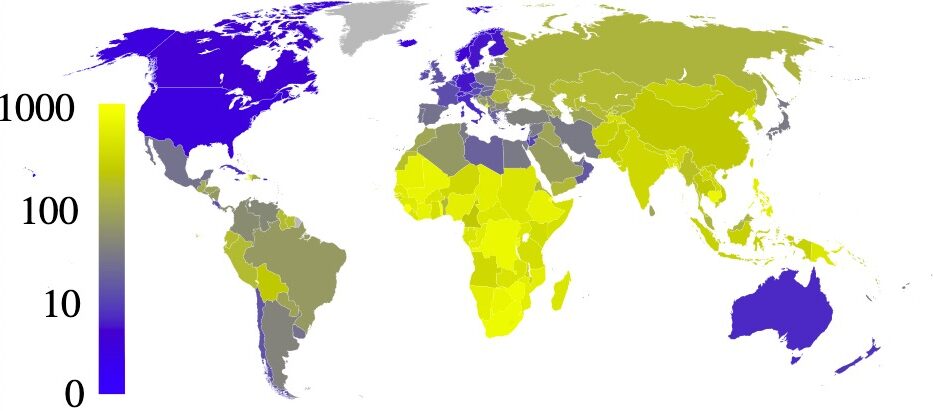

Estimated prevalence of tuberculosis per 100,000 people in 2007, per country

Image: “Estimated prevalence of tuberculosis” by Eubulides. License: Public DomainThe M. tuberculosis complex is a group of species that can cause TB in humans or other animals Animals Unicellular or multicellular, heterotrophic organisms, that have sensation and the power of voluntary movement. Under the older five kingdom paradigm, animalia was one of the kingdoms. Under the modern three domain model, animalia represents one of the many groups in the domain eukaryota. Cell Types: Eukaryotic versus Prokaryotic.

Key species:

Characteristics:

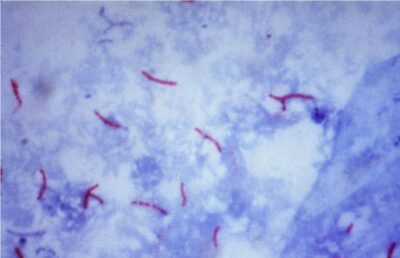

Acid-fast stain of M. tuberculosis

Image: “Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria” by CDC/Dr. George P. Kubica. License: Public DomainVirulence factors Virulence factors Those components of an organism that determine its capacity to cause disease but are not required for its viability per se. Two classes have been characterized: toxins, biological and surface adhesion molecules that affect the ability of the microorganism to invade and colonize a host. Haemophilus:

Transmission:

Tuberculosis disease (refers to the presence of signs or symptoms reflecting illness due to M. tuberculosis; the older terms are primary active disease, active tuberculosis (older term) active tuberculosis disease (older term):

Proliferation of bacteria Bacteria Bacteria are prokaryotic single-celled microorganisms that are metabolically active and divide by binary fission. Some of these organisms play a significant role in the pathogenesis of diseases. Bacteriology within alveolar macrophages Alveolar macrophages Round, granular, mononuclear phagocytes found in the alveoli of the lungs. They ingest small inhaled particles resulting in degradation and presentation of the antigen to immunocompetent cells. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

Latent infection:

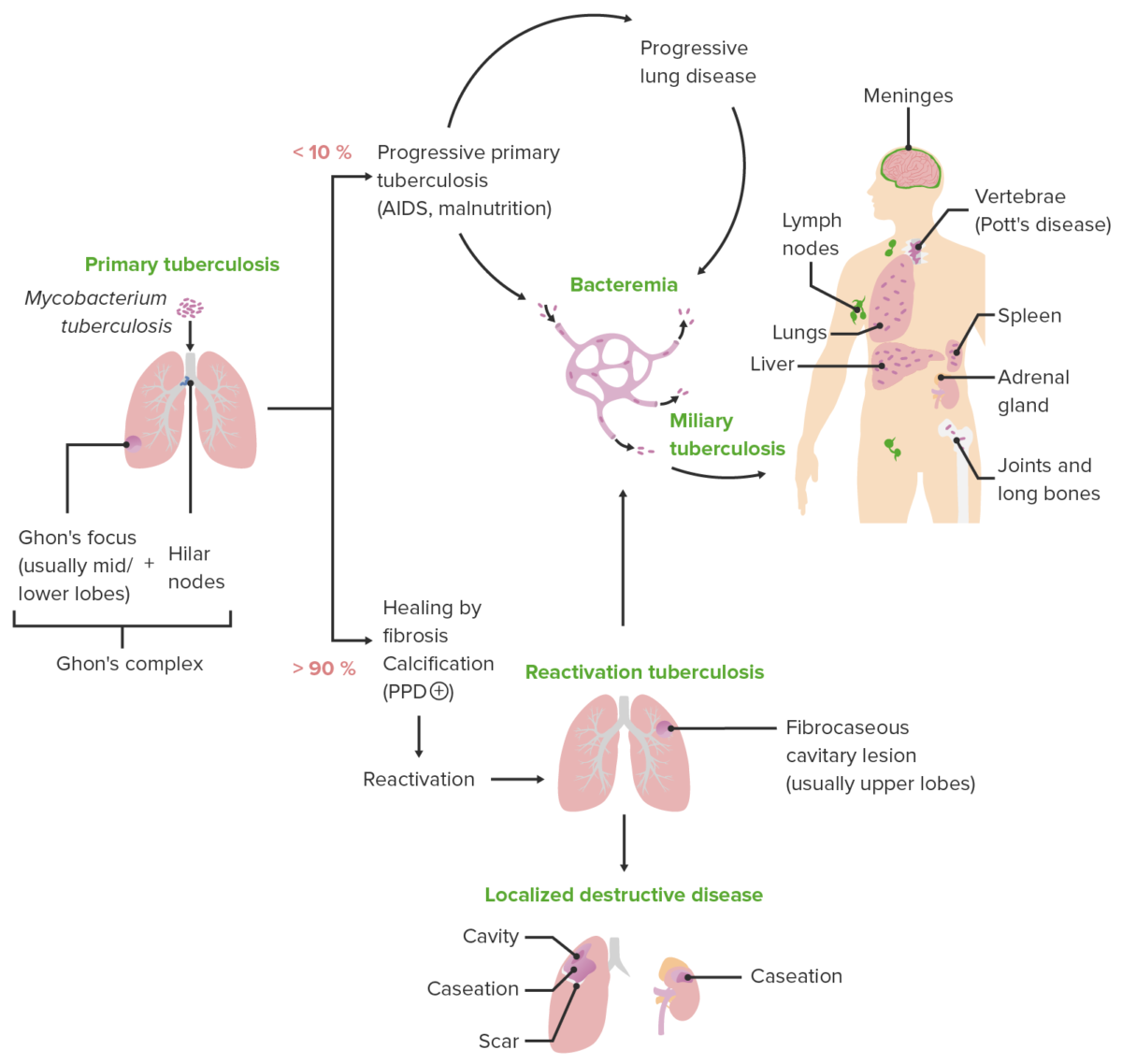

Schematic diagram depicting the various clinical presentations of tuberculosis along with the characteristic pathologic mechanisms of each presentation

Image by Lecturio. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Chest X-ray of Ghon’s complex of active TB (left lung)

Image: “Ghon’s complex” by Basem Abbas Al Ubaidi. License: CC BY 4.0

Chest X-ray of diffuse miliary infiltrates, characteristic of miliary TB

Image: “Chest radiograph of miliary tuberculosis” by Benjamín Herreros et al. License: CC BY 4.0

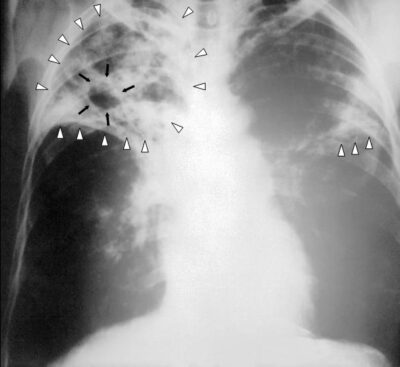

Chest X-ray of a patient with tuberculosis: bilateral reticular infiltrates (white triangles) and cavitary lesion (black arrows) in the right upper lobe

Image: “An anteroposterior X-ray” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. License: Public Domain

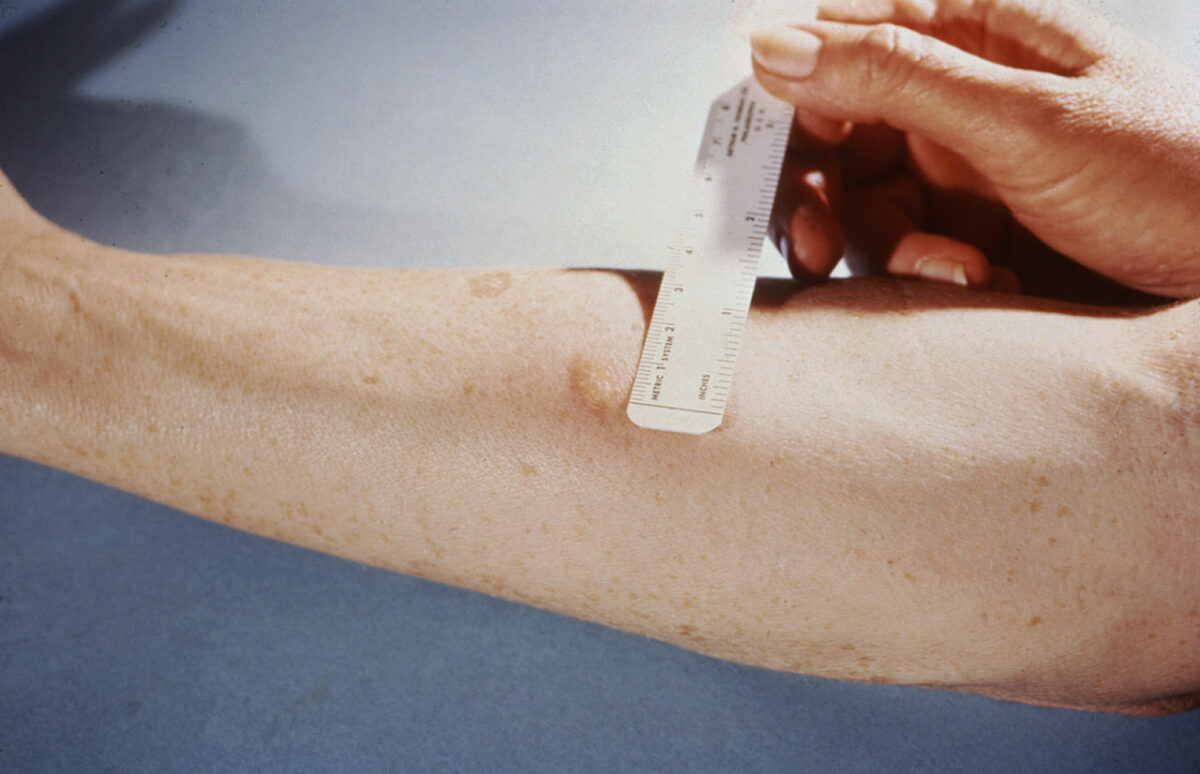

Measuring the reaction to a tuberculin skin test

Image: “Mendel-Mantoux-Test” by Public Health Image Library. License: Public Domain| Initial phase Initial Phase Sepsis in Children | Stabilization phase | |

|---|---|---|

| Active TB |

|

|

| Latent TB | Treatment options:

|

|