Necrotizing fasciitis is a life-threatening infection that causes rapid destruction and necrosis Necrosis The death of cells in an organ or tissue due to disease, injury or failure of the blood supply. Ischemic Cell Damage of the fascia Fascia Layers of connective tissue of variable thickness. The superficial fascia is found immediately below the skin; the deep fascia invests muscles, nerves, and other organs. Cellulitis and subcutaneous tissues. Patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship may present with significant pain Pain An unpleasant sensation induced by noxious stimuli which are detected by nerve endings of nociceptive neurons. Pain: Types and Pathways out of proportion to the presenting symptoms and rapidly progressive erythema Erythema Redness of the skin produced by congestion of the capillaries. This condition may result from a variety of disease processes. Chalazion of the affected area. Most patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship will also have systemic signs of infection, including fever Fever Fever is defined as a measured body temperature of at least 38°C (100.4°F). Fever is caused by circulating endogenous and/or exogenous pyrogens that increase levels of prostaglandin E2 in the hypothalamus. Fever is commonly associated with chills, rigors, sweating, and flushing of the skin. Fever, hypotension Hypotension Hypotension is defined as low blood pressure, specifically < 90/60 mm Hg, and is most commonly a physiologic response. Hypotension may be mild, serious, or life threatening, depending on the cause. Hypotension, altered mental status Altered Mental Status Sepsis in Children, and multisystem organ failure. The diagnosis is primarily clinical since patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship can quickly progress to septic shock Septic shock Sepsis associated with hypotension or hypoperfusion despite adequate fluid resuscitation. Perfusion abnormalities may include, but are not limited to lactic acidosis; oliguria; or acute alteration in mental status. Sepsis and Septic Shock without source control Source Control Surgical Infections. This type of infection is a surgical emergency Surgical Emergency Acute Abdomen and requires emergent surgical debridement Debridement The removal of foreign material and devitalized or contaminated tissue from or adjacent to a traumatic or infected lesion until surrounding healthy tissue is exposed. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, parenteral antibiotics, and close hemodynamic monitoring.

Last updated: Dec 15, 2025

Necrotizing fasciitis is divided into microbiologic categories based on the causative organism(s):

Early signs:

Late signs:

Common sites of infection:

Rapidly spreading erythema, ulceration, and edema of the right leg due to necrotizing fasciitis

Image: “Preoperative photograph” by Department of Family Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300A, Atlanta, GA 30344, USA. License: CC BY 3.0

Bullae and erythema resulting from necrotizing fasciitis

Image: “Superficial skin manifestations of necrotizing fasciitis” by National Hospital of Sri Lanka, Regent Street, Colombo 10, Sri Lanka. License: CC BY 4.0

Cutaneous necrosis, erythema, and bullous changes due to necrotizing fasciitis of the leg

Image: “Necrotizing fasciitis” by Piotr Smuszkiewicz et al. License: CC BY 2.0

Fournier gangrene:

Significant erythema and edema is noted throughout the scrotum and gluteal regions.

Erythema and necrotic tissue due to necrotizing fasciitis of the neck:

This developed after a dental extraction.

Necrotizing fasciitis of the lip and face:

Significant swelling, erythema, exfoliation, and purulent drainage is noted.

A definitive diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis is made by surgical exploration and debridement Debridement The removal of foreign material and devitalized or contaminated tissue from or adjacent to a traumatic or infected lesion until surrounding healthy tissue is exposed. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. These processes should not be delayed to obtain diagnostic information, if the clinical suspicion is high.

However, the following may be helpful:

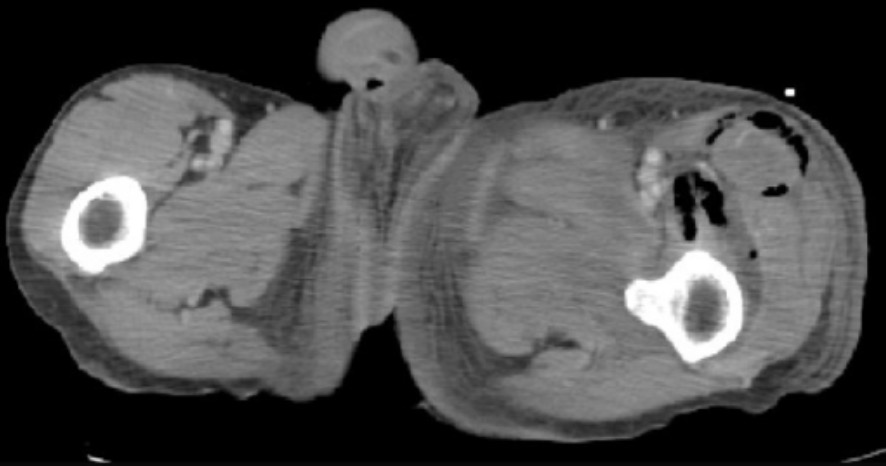

CT findings in necrotizing fasciitis:

Gas is noted in the subcutaneous space.

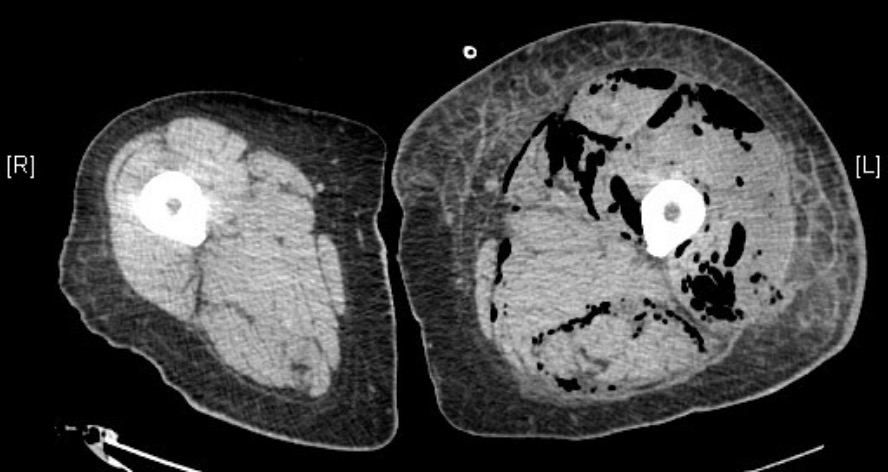

CT findings in necrotizing fasciitis:

This scan demonstrates fascial edema, subcutaneous fat stranding, and gas in the muscle compartments.

CT findings in necrotizing fasciitis:

This scan demonstrates subcutaneous gas tracking along fascial planes of the left leg and pelvis.

Surgical debridement Debridement The removal of foreign material and devitalized or contaminated tissue from or adjacent to a traumatic or infected lesion until surrounding healthy tissue is exposed. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome is the mainstay of treatment.

Surgical excision of necrotic tissues in necrotizing fasciitis

Image: “Management of necrotizing fasciitis” by 3rd Department of Surgery, Attikon University Hospital, University of Athens School of Medicine, Athens, Greece. License: CC BY 4.0