Croup, also known as laryngotracheobronchitis, is a disease most commonly caused by a viral infection that leads to severe inflammation of the upper airway. It usually presents in children < 5 years of age. Patients develop a hoarse, “seal-like” barking cough and inspiratory stridor. Human parainfluenza viruses account for the majority of cases, followed by respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, and enteroviruses. Croup is usually diagnosed clinically or with the aid of X-ray imaging, which may show a narrowing of the air column in the trachea called the “steeple sign”). Treatment consists of steroids and epinephrine.

Last updated: May 21, 2025

Transmission

Risk factors

Croup is commonly caused by a virus Virus Viruses are infectious, obligate intracellular parasites composed of a nucleic acid core surrounded by a protein capsid. Viruses can be either naked (non-enveloped) or enveloped. The classification of viruses is complex and based on many factors, including type and structure of the nucleoid and capsid, the presence of an envelope, the replication cycle, and the host range. Virology (75% of cases) and less commonly by bacteria Bacteria Bacteria are prokaryotic single-celled microorganisms that are metabolically active and divide by binary fission. Some of these organisms play a significant role in the pathogenesis of diseases. Bacteriology.

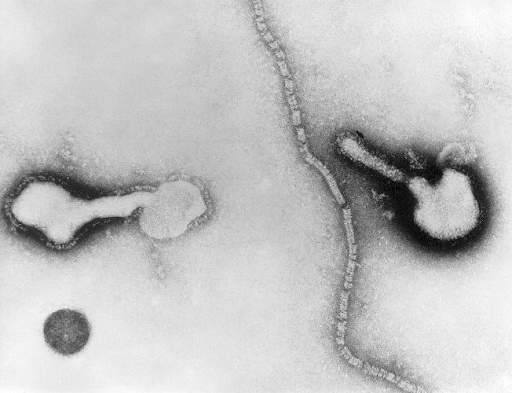

Transmission electron micrograph of parainfluenza virus

Image: “Transmission electron micrograph” by Public Health Image Library. License: CDC/Public Domain| Feature | Number of points assigned for this feature | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Chest wall Chest wall The chest wall consists of skin, fat, muscles, bones, and cartilage. The bony structure of the chest wall is composed of the ribs, sternum, and thoracic vertebrae. The chest wall serves as armor for the vital intrathoracic organs and provides the stability necessary for the movement of the shoulders and arms. Chest Wall: Anatomy retraction | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Stridor Stridor Laryngomalacia and Tracheomalacia | None | With agitation Agitation A feeling of restlessness associated with increased motor activity. This may occur as a manifestation of nervous system drug toxicity or other conditions. St. Louis Encephalitis Virus | At rest | |||

| Cyanosis Cyanosis A bluish or purplish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes due to an increase in the amount of deoxygenated hemoglobin in the blood or a structural defect in the hemoglobin molecule. Pulmonary Examination | None | With agitation Agitation A feeling of restlessness associated with increased motor activity. This may occur as a manifestation of nervous system drug toxicity or other conditions. St. Louis Encephalitis Virus | At rest | |||

| Level of consciousness | Normal | Disoriented | ||||

| Air entry | Normal | Decreased | Markedly decreased | |||

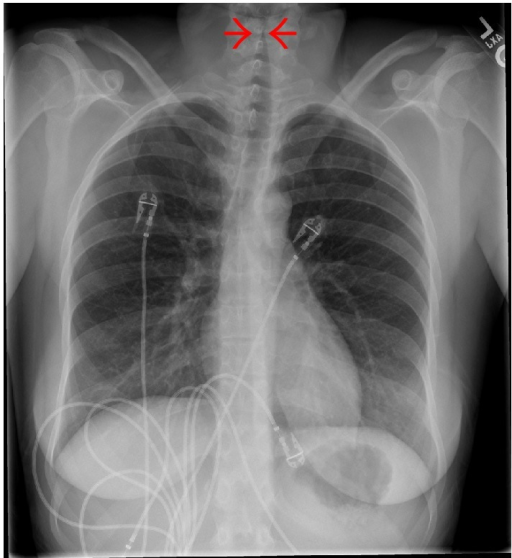

Tip: While a chest X-ray X-ray Penetrating electromagnetic radiation emitted when the inner orbital electrons of an atom are excited and release radiant energy. X-ray wavelengths range from 1 pm to 10 nm. Hard x-rays are the higher energy, shorter wavelength x-rays. Soft x-rays or grenz rays are less energetic and longer in wavelength. The short wavelength end of the x-ray spectrum overlaps the gamma rays wavelength range. The distinction between gamma rays and x-rays is based on their radiation source. Pulmonary Function Tests will show a narrowing of the air column in the trachea Trachea The trachea is a tubular structure that forms part of the lower respiratory tract. The trachea is continuous superiorly with the larynx and inferiorly becomes the bronchial tree within the lungs. The trachea consists of a support frame of semicircular, or C-shaped, rings made out of hyaline cartilage and reinforced by collagenous connective tissue. Trachea: Anatomy ( steeple sign Steeple Sign Pediatric Chest Abnormalities), a chest X-ray X-ray Penetrating electromagnetic radiation emitted when the inner orbital electrons of an atom are excited and release radiant energy. X-ray wavelengths range from 1 pm to 10 nm. Hard x-rays are the higher energy, shorter wavelength x-rays. Soft x-rays or grenz rays are less energetic and longer in wavelength. The short wavelength end of the x-ray spectrum overlaps the gamma rays wavelength range. The distinction between gamma rays and x-rays is based on their radiation source. Pulmonary Function Tests is rarely done in practice and is always the wrong answer if a question stem asks what the most appropriate next step in diagnosis is. This is because the diagnosis is based on the clinical signs of a “seal-like” barking cough and inspiratory stridor Stridor Laryngomalacia and Tracheomalacia.

Chest X-ray showing subglottic stenosis, known as steeple sign, commonly seen on anteroposterior X-ray in patients with croup.

Image: “Steeple sign” by Jayshil J. Patel, Emily Kitchin, and Kurt Pfeifer. License: CC BY 4.0