Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is caused by malignant proliferation of atypical keratinocytes Keratinocytes Epidermal cells which synthesize keratin and undergo characteristic changes as they move upward from the basal layers of the epidermis to the cornified (horny) layer of the skin. Successive stages of differentiation of the keratinocytes forming the epidermal layers are basal cell, spinous or prickle cell, and the granular cell. Skin: Structure and Functions. This condition is the 2nd most common skin Skin The skin, also referred to as the integumentary system, is the largest organ of the body. The skin is primarily composed of the epidermis (outer layer) and dermis (deep layer). The epidermis is primarily composed of keratinocytes that undergo rapid turnover, while the dermis contains dense layers of connective tissue. Skin: Structure and Functions malignancy Malignancy Hemothorax and usually affects sun-exposed areas of fair-skinned patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship. The cancer presents as a firm, erythematous, keratotic plaque Plaque Primary Skin Lesions or papule Papule Elevated lesion < 1 cm in diameter Generalized and Localized Rashes. Histopathologic examination should be done for all suspected cases, as many lesions, such as actinic keratosis Actinic keratosis Actinic keratosis (AK) is a precancerous skin lesion that affects sun-exposed areas. The condition presents as small, non-tender macules/papules with a characteristic sandpaper-like texture that can become erythematous scaly plaques. Actinic Keratosis, mimic the appearance of SCC. Surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment. Overall prognosis Prognosis A prediction of the probable outcome of a disease based on a individual's condition and the usual course of the disease as seen in similar situations. Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas is excellent for completely excised lesions, but certain high-risk features may predispose to metastatic disease and poor outcomes.

Last updated: Dec 15, 2025

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is a malignant tumor Tumor Inflammation of the skin Skin The skin, also referred to as the integumentary system, is the largest organ of the body. The skin is primarily composed of the epidermis (outer layer) and dermis (deep layer). The epidermis is primarily composed of keratinocytes that undergo rapid turnover, while the dermis contains dense layers of connective tissue. Skin: Structure and Functions arising from epidermal keratinocytes Keratinocytes Epidermal cells which synthesize keratin and undergo characteristic changes as they move upward from the basal layers of the epidermis to the cornified (horny) layer of the skin. Successive stages of differentiation of the keratinocytes forming the epidermal layers are basal cell, spinous or prickle cell, and the granular cell. Skin: Structure and Functions.

Occurence:

cSCC can occur on any cutaneous surface, including trunk, extremities, face, and oral and anogenital mucosa.

Morphology:

Color: varies from flesh-colored to erythematous

Symptoms:

Marjolin’s ulcer:

Keratoacanthoma:

Verrucous carcinoma:

SCC of the lip: nodule Nodule Chalazion or plaque Plaque Primary Skin Lesions usually on the lower lip

Oral SCC: ulcer, nodule Nodule Chalazion or plaque Plaque Primary Skin Lesions in the oral cavity

Squamous cell carcinoma of the nose:

Ulcerating lesion noted in this sun-exposed area

Squamous cell carcinoma:

A pink raised lesion on the skin of the face

Marjolin’s ulcer:

Development of Marjolin’s ulcer in a long-standing burn scar of the forearm

History:

Physical exam:

Dermoscopy Dermoscopy A noninvasive technique that enables direct microscopic examination of the surface and architecture of the skin. Seborrheic Keratosis:

Biopsy Biopsy Removal and pathologic examination of specimens from the living body. Ewing Sarcoma:

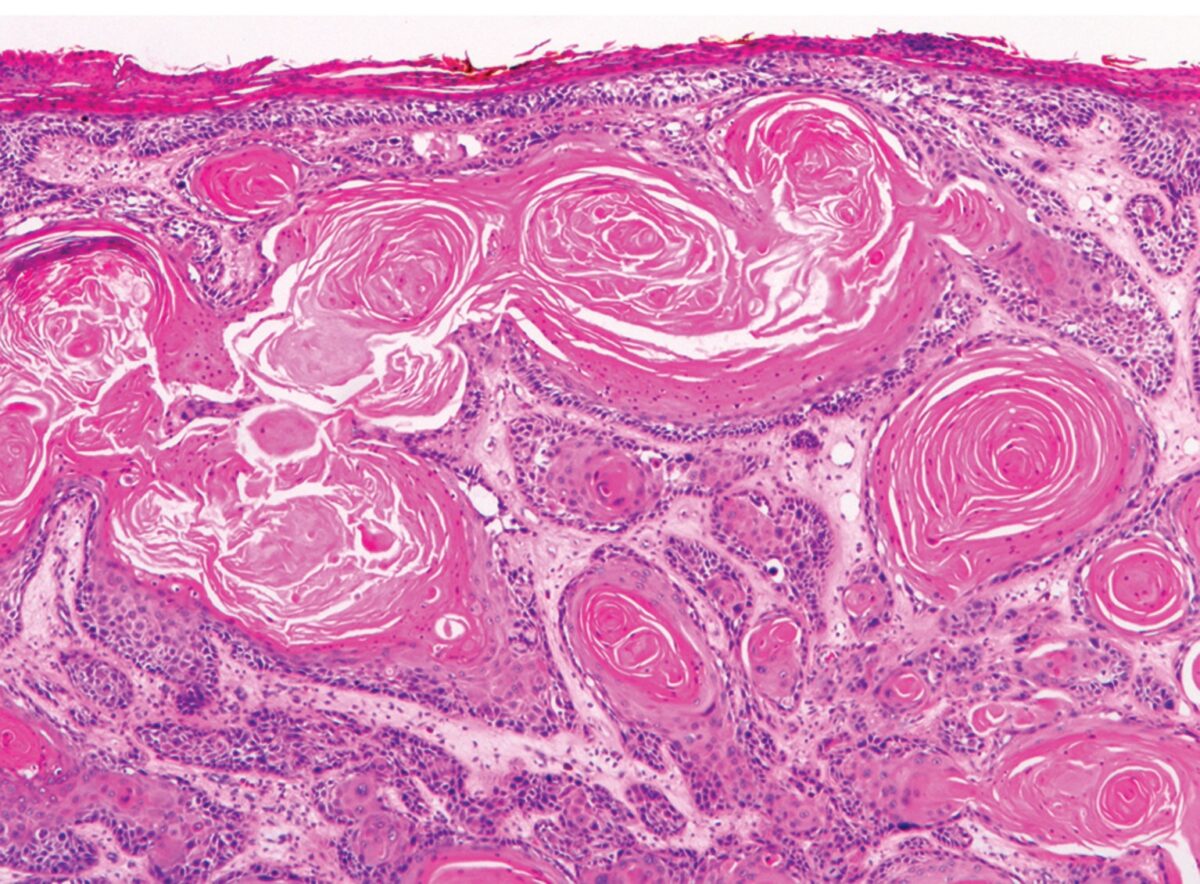

Invasive SCC:

Well-differentiated lesions showing prominent keratinization structures (keratin pearls)

American Joint Commission on Cancer 2018 TNM system TNM system Grading, Staging, and Metastasis:

Only applicable to SCC of the head and neck Neck The part of a human or animal body connecting the head to the rest of the body. Peritonsillar Abscess area (lip, ear, face, scalp, and neck Neck The part of a human or animal body connecting the head to the rest of the body. Peritonsillar Abscess).

Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) staging Staging Methods which attempt to express in replicable terms the extent of the neoplasm in the patient. Grading, Staging, and Metastasis:

Standard surgical excision:

Mohs micrographic surgery:

Alternatives to surgery (not for high-risk lesions):

Radiation Radiation Emission or propagation of acoustic waves (sound), electromagnetic energy waves (such as light; radio waves; gamma rays; or x-rays), or a stream of subatomic particles (such as electrons; neutrons; protons; or alpha particles). Osteosarcoma:

Systemic treatment: