Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder of reproductive-age women, affecting nearly 5%‒10% of women in the age group. Characterized by hyperandrogenism Hyperandrogenism A condition caused by the excessive secretion of androgens from the adrenal cortex; the ovaries; or the testes. The clinical significance in males is negligible. In women, the common manifestations are hirsutism and virilism as seen in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and adrenocortical hyperfunction. Potassium-sparing Diuretics, chronic anovulation leading to oligomenorrhea (or amenorrhea Amenorrhea Absence of menstruation. Congenital Malformations of the Female Reproductive System), and metabolic dysfunction, PCOS increases a woman’s risk for infertility Infertility Infertility is the inability to conceive in the context of regular intercourse. The most common causes of infertility in women are related to ovulatory dysfunction or tubal obstruction, whereas, in men, abnormal sperm is a common cause. Infertility, endometrial hyperplasia Hyperplasia An increase in the number of cells in a tissue or organ without tumor formation. It differs from hypertrophy, which is an increase in bulk without an increase in the number of cells. Cellular Adaptation or carcinoma, and cardiovascular disease. The pathophysiology is incompletely understood but thought to have a multifactorial genetic basis, causing altered pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone Gonadotropin-releasing hormone A decapeptide that stimulates the synthesis and secretion of both pituitary gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone. Gnrh is produced by neurons in the septum preoptic area of the hypothalamus and released into the pituitary portal blood, leading to stimulation of gonadotrophs in the anterior pituitary gland. Puberty (GnRH), as well as increases in luteinizing hormone ( LH LH A major gonadotropin secreted by the adenohypophysis. Luteinizing hormone regulates steroid production by the interstitial cells of the testis and the ovary. The preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge in females induces ovulation, and subsequent luteinization of the follicle. Luteinizing hormone consists of two noncovalently linked subunits, alpha and beta. Within a species, the alpha subunit is common in the three pituitary glycoprotein hormones (TSH, LH, and FSH), but the beta subunit is unique and confers its biological specificity. Menstrual Cycle), androgens Androgens Androgens are naturally occurring steroid hormones responsible for development and maintenance of the male sex characteristics, including penile, scrotal, and clitoral growth, development of sexual hair, deepening of the voice, and musculoskeletal growth. Androgens and Antiandrogens, and estrogen Estrogen Compounds that interact with estrogen receptors in target tissues to bring about the effects similar to those of estradiol. Estrogens stimulate the female reproductive organs, and the development of secondary female sex characteristics. Estrogenic chemicals include natural, synthetic, steroidal, or non-steroidal compounds. Ovaries: Anatomy (from peripheral aromatization in adipose tissue). The result is chronic anovulation and hirsutism, which define the condition. Diagnosis is one of exclusion; therefore, other causes of abnormal uterine bleeding Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Abnormal uterine bleeding is the medical term for abnormalities in the frequency, volume, duration, and regularity of the menstrual cycle. Abnormal uterine bleeding is classified using the acronym PALM-COEIN, with PALM representing the structural causes and COEIN indicating the non-structural causes. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding and hirsutism must be ruled out. Management includes attempting to restore normal ovulation Ovulation The discharge of an ovum from a rupturing follicle in the ovary. Menstrual Cycle through weight loss Weight loss Decrease in existing body weight. Bariatric Surgery, oral contraceptive Oral contraceptive Compounds, usually hormonal, taken orally in order to block ovulation and prevent the occurrence of pregnancy. The hormones are generally estrogen or progesterone or both. Benign Liver Tumors pills (OCPs), and fertility assistance.

Last updated: Apr 17, 2023

The exact mechanisms are unknown, but thought to be complex and include both genetic and environmental factors. Metabolic syndrome Metabolic syndrome Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions that significantly increases the risk for several secondary diseases, notably cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver. In general, it is agreed that hypertension, insulin resistance/hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia, along with central obesity, are components of the metabolic syndrome. Metabolic Syndrome and obesity Obesity Obesity is a condition associated with excess body weight, specifically with the deposition of excessive adipose tissue. Obesity is considered a global epidemic. Major influences come from the western diet and sedentary lifestyles, but the exact mechanisms likely include a mixture of genetic and environmental factors. Obesity are often, but not always, present and likely contribute to the pathophysiology in some individuals.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) should be suspected in any reproductive-age female with irregular menses Menses The periodic shedding of the endometrium and associated menstrual bleeding in the menstrual cycle of humans and primates. Menstruation is due to the decline in circulating progesterone, and occurs at the late luteal phase when luteolysis of the corpus luteum takes place. Menstrual Cycle and/or symptoms of hyperandrogenism Hyperandrogenism A condition caused by the excessive secretion of androgens from the adrenal cortex; the ovaries; or the testes. The clinical significance in males is negligible. In women, the common manifestations are hirsutism and virilism as seen in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and adrenocortical hyperfunction. Potassium-sparing Diuretics, especially if obese or presenting with infertility Infertility Infertility is the inability to conceive in the context of regular intercourse. The most common causes of infertility in women are related to ovulatory dysfunction or tubal obstruction, whereas, in men, abnormal sperm is a common cause. Infertility.

Hirsutism in PCOS:

Hair is noted along the side burns, chin, and upper lip; signs of hyperandrogenism.

Male-pattern alopecia in PCOS:

The patient has frontal hair thinning, which is a sign of hyperandrogenism.

Acanthosis nigricans in PCOS:

Thickened, darkened skin can appear on the nape of the neck, axillae, or skinfolds as a sign of high insulin levels from insulin resistance.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a diagnosis of exclusion, so other causes of oligo- or amenorrhea Amenorrhea Absence of menstruation. Congenital Malformations of the Female Reproductive System and hyperandrogenism Hyperandrogenism A condition caused by the excessive secretion of androgens from the adrenal cortex; the ovaries; or the testes. The clinical significance in males is negligible. In women, the common manifestations are hirsutism and virilism as seen in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and adrenocortical hyperfunction. Potassium-sparing Diuretics must be ruled out. The Rotterdam criteria are commonly used to make the diagnosis once other causes are excluded.

Diagnosis requires 2 of the 3 following criteria:

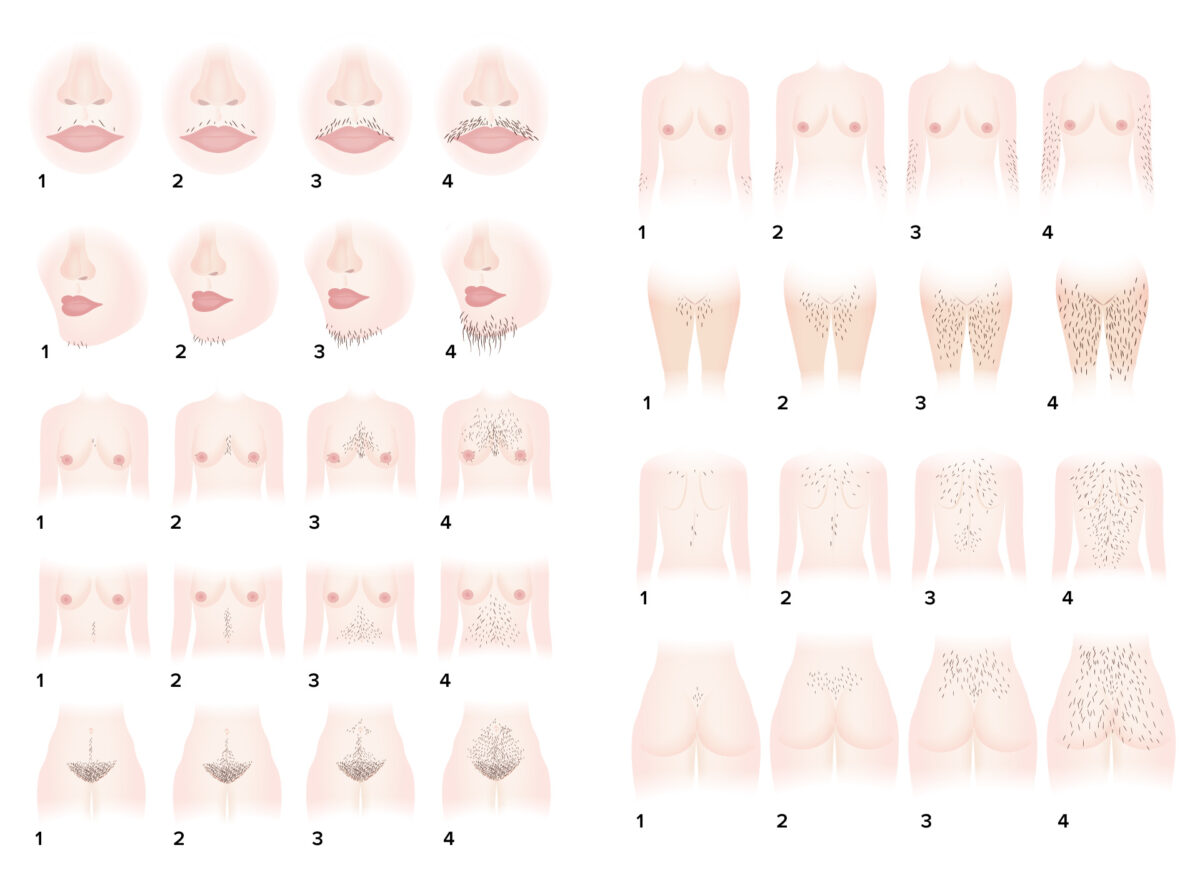

Ferriman-Gallwey hirsutism scoring system: a system for objective assessment of the degree of hirsutism

Image by Lecturio.| Hormones Hormones Hormones are messenger molecules that are synthesized in one part of the body and move through the bloodstream to exert specific regulatory effects on another part of the body. Hormones play critical roles in coordinating cellular activities throughout the body in response to the constant changes in both the internal and external environments. Hormones: Overview and Types ↑ in PCOS | Hormones Hormones Hormones are messenger molecules that are synthesized in one part of the body and move through the bloodstream to exert specific regulatory effects on another part of the body. Hormones play critical roles in coordinating cellular activities throughout the body in response to the constant changes in both the internal and external environments. Hormones: Overview and Types ↓ in PCOS |

|---|---|

|

|

FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone

HDL: high-density lipoproteins

LDL: low-density lipoproteins

LH: luteinizing hormone

PCOS: polycystic ovarian syndrome

SHBG: sex hormone-binding globulin

Ultrasound of a polycystic-appearing ovary:

Note the classic “pearls on a string” around the periphery of the ovary identifying the abnormally developing follicles seen in PCOS. Polycystic appearing ovaries are seen in approximately ⅔ of patients with PCOS and is 1 of the 3 diagnostic Rotterdam criteria.

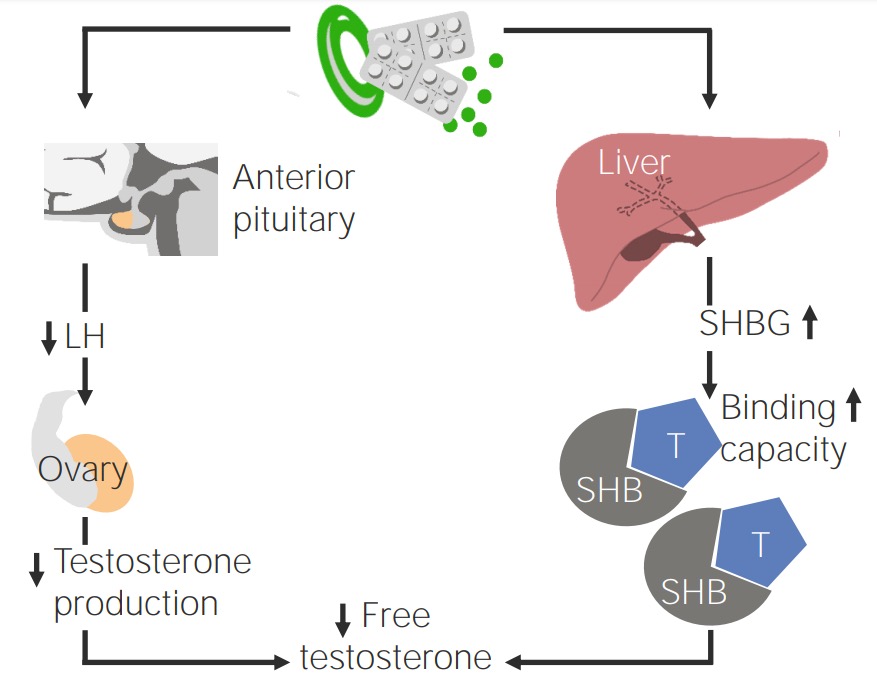

Effect of oral contraception on patients with PCOS

Image by Lecturio.