Scabies is an infestation of the skin Skin The skin, also referred to as the integumentary system, is the largest organ of the body. The skin is primarily composed of the epidermis (outer layer) and dermis (deep layer). The epidermis is primarily composed of keratinocytes that undergo rapid turnover, while the dermis contains dense layers of connective tissue. Skin: Structure and Functions by the Sarcoptes scabiei mite, which presents most commonly with intense pruritus Pruritus An intense itching sensation that produces the urge to rub or scratch the skin to obtain relief. Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema), characteristic linear burrows Burrows Dermatologic Examination, and erythematous papules, particularly in the interdigital folds and the flexor aspects of the wrists. Direct and prolonged human-to-human contact is the biggest risk factor for transmission. Diagnosis is most often clinical but can be confirmed by microscopic examination of skin Skin The skin, also referred to as the integumentary system, is the largest organ of the body. The skin is primarily composed of the epidermis (outer layer) and dermis (deep layer). The epidermis is primarily composed of keratinocytes that undergo rapid turnover, while the dermis contains dense layers of connective tissue. Skin: Structure and Functions scrapings or by dermatoscopy. Treatment includes permethrin cream for both the patient and close personal contacts (cohabitants and sexual partners) as well as thorough cleaning of bedding and clothing.

Last updated: May 19, 2025

Adult Sarcoptes mite taken from the skin scraping of the dead Himalayan lynx

Image: “Adult Sarcoptes mite taken from the skin scraping of the dead Himalayan lynx” by Department of Zoology, Mirpur University of Science & Technology (MUST), Mirpur Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Pakistan. License: CC BY 4.0Sarcoptes scabiei (var. hominis) causes human scabies.

Humans are the primary reservoir Reservoir Animate or inanimate sources which normally harbor disease-causing organisms and thus serve as potential sources of disease outbreaks. Reservoirs are distinguished from vectors (disease vectors) and carriers, which are agents of disease transmission rather than continuing sources of potential disease outbreaks. Humans may serve both as disease reservoirs and carriers. Escherichia coli of S. scabiei.

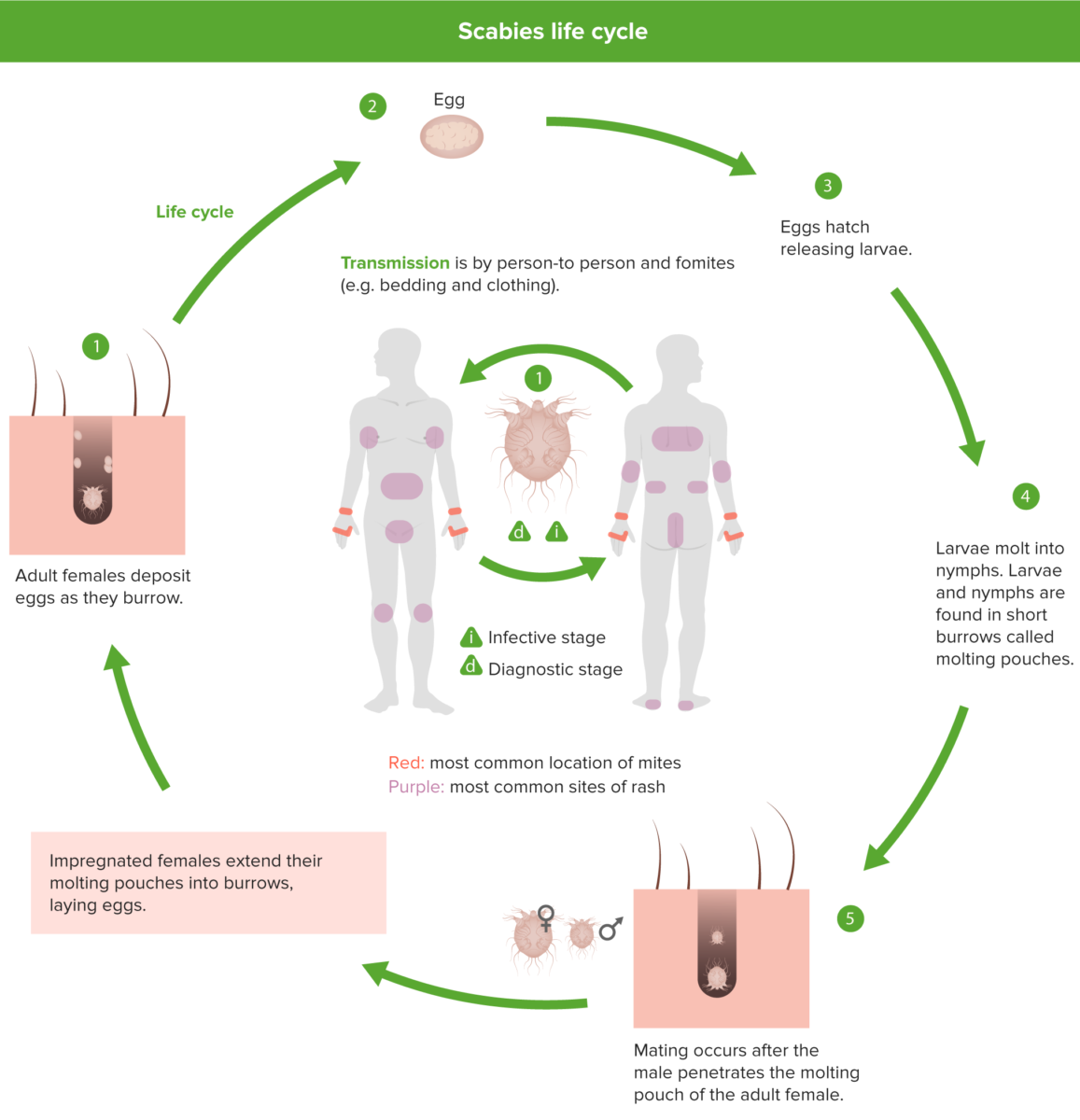

The 4 stages in the S. scabiei life cycle: egg, larva, nymph, and adult

1: Females deposit 2–3 eggs per day as they burrow under the skin.

2: Eggs are oval, 0.10–0.15 mm in length, and hatch in 3–4 days.

3: After the eggs hatch, the larvae migrate to the skin surface and burrow into the intact stratum corneum to construct almost-invisible, short burrows called molting pouches.

4: The resulting nymphs have 4 pairs of legs.

5: Mating occurs after the active male penetrates the molting pouch of the adult female.

The infestation takes the form of:

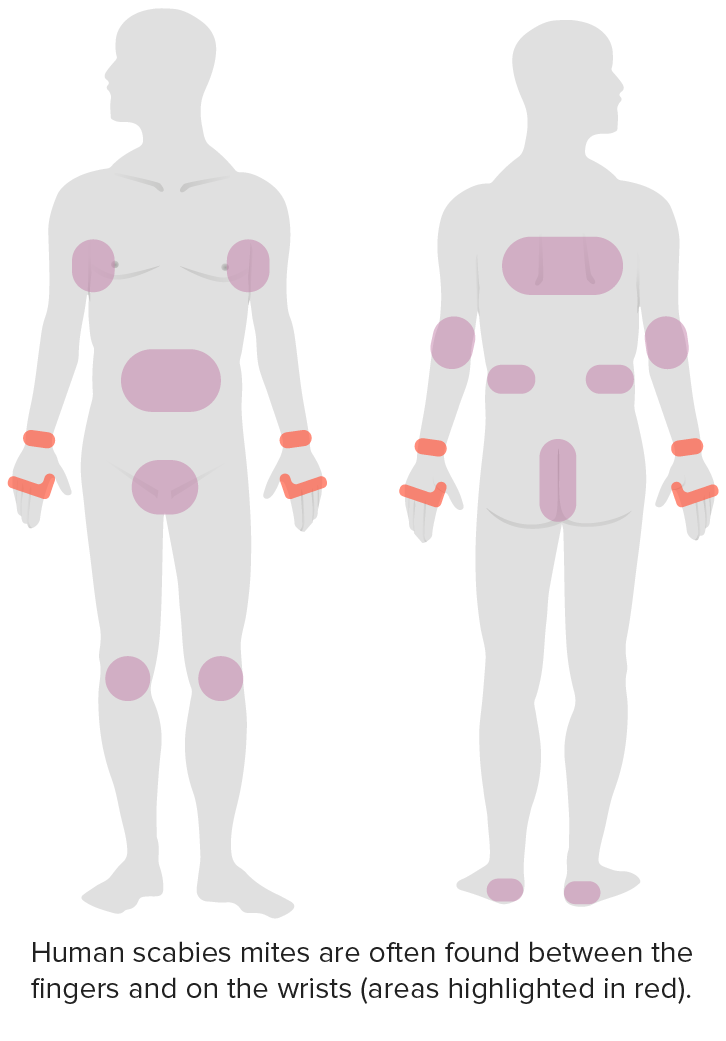

Distribution of scabies

Image by Lecturio.

Scabies infestation with visible burrows

Image: “Scabies infestation with visible burrow” by Saint Louis University, Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital, 1465 South Grand Avenue, St. Louis, MO 63104, USA. License: CC-BY-4.0

Multiple excoriations and small, erythematous papules, all of which cause itchiness

Image: “ScabiesD08” by Cixia. License: Public DomainDiagnosis is confirmed through the detection of scabies mites, eggs, or fecal pellets (scybala) through microscopic examination. However, diagnosis can be clinically based on history and physical examination findings.

Occasionally, scabies may be misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis Dermatitis Any inflammation of the skin. Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema). This often occurs due to the appearance of the erythematous papules. Patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship who are misdiagnosed will have initial symptom alleviation with topical glucocorticoids Glucocorticoids Glucocorticoids are a class within the corticosteroid family. Glucocorticoids are chemically and functionally similar to endogenous cortisol. There are a wide array of indications, which primarily benefit from the antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of this class of drugs. Glucocorticoids; however, this will not treat the underlying cause (i.e., mite infestation).

Close-up photo of a scabies burrow. The large scaly patch at the left is due to scratching. The scabies mite traveled toward the upper right and can be seen at the end of the burrow.

Image: “Close-up photo of a scabies burrow” by Michael Geary. License: Public Domain2 pillars of successful therapy in scabies:

Decontaminate bedding, towels, and clothing via: