Wilson disease (hepatolenticular degeneration) is an autosomal recessive Autosomal recessive Autosomal inheritance, both dominant and recessive, refers to the transmission of genes from the 22 autosomal chromosomes. Autosomal recessive diseases are only expressed when 2 copies of the recessive allele are inherited. Autosomal Recessive and Autosomal Dominant Inheritance disorder caused by various mutations in the ATP7B gene Gene A category of nucleic acid sequences that function as units of heredity and which code for the basic instructions for the development, reproduction, and maintenance of organisms. Basic Terms of Genetics, which regulates copper Copper A heavy metal trace element with the atomic symbol cu, atomic number 29, and atomic weight 63. 55. Trace Elements transport within hepatocytes Hepatocytes The main structural component of the liver. They are specialized epithelial cells that are organized into interconnected plates called lobules. Liver: Anatomy. Dysfunction of this transport mechanism leads to abnormal copper Copper A heavy metal trace element with the atomic symbol cu, atomic number 29, and atomic weight 63. 55. Trace Elements accumulations in the liver Liver The liver is the largest gland in the human body. The liver is found in the superior right quadrant of the abdomen and weighs approximately 1.5 kilograms. Its main functions are detoxification, metabolism, nutrient storage (e.g., iron and vitamins), synthesis of coagulation factors, formation of bile, filtration, and storage of blood. Liver: Anatomy, brain Brain The part of central nervous system that is contained within the skull (cranium). Arising from the neural tube, the embryonic brain is comprised of three major parts including prosencephalon (the forebrain); mesencephalon (the midbrain); and rhombencephalon (the hindbrain). The developed brain consists of cerebrum; cerebellum; and other structures in the brain stem. Nervous System: Anatomy, Structure, and Classification, eyes, and other organs, with consequent major and variably expressed hepatic, neurologic, and psychiatric disturbances. Liver Liver The liver is the largest gland in the human body. The liver is found in the superior right quadrant of the abdomen and weighs approximately 1.5 kilograms. Its main functions are detoxification, metabolism, nutrient storage (e.g., iron and vitamins), synthesis of coagulation factors, formation of bile, filtration, and storage of blood. Liver: Anatomy involvement may manifest as hepatitis, liver failure Liver failure Severe inability of the liver to perform its normal metabolic functions, as evidenced by severe jaundice and abnormal serum levels of ammonia; bilirubin; alkaline phosphatase; aspartate aminotransferase; lactate dehydrogenases; and albumin/globulin ratio. Autoimmune Hepatitis, or cirrhosis Cirrhosis Cirrhosis is a late stage of hepatic parenchymal necrosis and scarring (fibrosis) most commonly due to hepatitis C infection and alcoholic liver disease. Patients may present with jaundice, ascites, and hepatosplenomegaly. Cirrhosis can also cause complications such as hepatic encephalopathy, portal hypertension, portal vein thrombosis, and hepatorenal syndrome. Cirrhosis, while basal ganglia Basal Ganglia Basal ganglia are a group of subcortical nuclear agglomerations involved in movement, and are located deep to the cerebral hemispheres. Basal ganglia include the striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen), globus pallidus, substantia nigra, and subthalamic nucleus. Basal Ganglia: Anatomy involvement causes the extrapyramidal signs. Most patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship are diagnosed between the ages of 5 and 35 years (mean: 13 years). Diagnosis is established if the patient has low plasma Plasma The residual portion of blood that is left after removal of blood cells by centrifugation without prior blood coagulation. Transfusion Products ceruloplasmin, corneal deposits of copper Copper A heavy metal trace element with the atomic symbol cu, atomic number 29, and atomic weight 63. 55. Trace Elements (Kayser-Fleischer rings), and elevated copper Copper A heavy metal trace element with the atomic symbol cu, atomic number 29, and atomic weight 63. 55. Trace Elements levels in the urine. However, other tests are often needed since not all patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship will have all these findings. The prognosis Prognosis A prediction of the probable outcome of a disease based on a individual's condition and the usual course of the disease as seen in similar situations. Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas is good for patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship without advanced liver Liver The liver is the largest gland in the human body. The liver is found in the superior right quadrant of the abdomen and weighs approximately 1.5 kilograms. Its main functions are detoxification, metabolism, nutrient storage (e.g., iron and vitamins), synthesis of coagulation factors, formation of bile, filtration, and storage of blood. Liver: Anatomy disease and for those who are treated with the chelating agents penicillamine or trientine Trientine An ethylenediamine derivative used as stabilizer for epoxy resins, as ampholyte for isoelectric focusing and as chelating agent for copper in hepatolenticular degeneration. Antidotes of Common Poisonings. Untreated Wilson disease is ultimately fatal, with patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship dying from cirrhosis Cirrhosis Cirrhosis is a late stage of hepatic parenchymal necrosis and scarring (fibrosis) most commonly due to hepatitis C infection and alcoholic liver disease. Patients may present with jaundice, ascites, and hepatosplenomegaly. Cirrhosis can also cause complications such as hepatic encephalopathy, portal hypertension, portal vein thrombosis, and hepatorenal syndrome. Cirrhosis, acute liver failure Liver failure Severe inability of the liver to perform its normal metabolic functions, as evidenced by severe jaundice and abnormal serum levels of ammonia; bilirubin; alkaline phosphatase; aspartate aminotransferase; lactate dehydrogenases; and albumin/globulin ratio. Autoimmune Hepatitis, or complications due to progressive neurologic disease.

Last updated: Jun 8, 2025

Wilson disease usually presents in children and young adults. It rarely manifests after 40 years of age. Manifestations are primarily hepatic, neurologic, and psychiatric and may include:

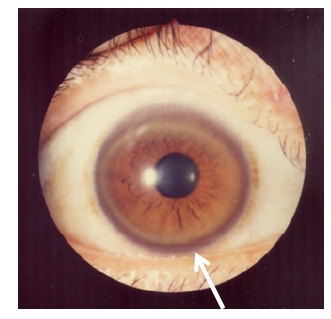

Kayser-Fleischer ring: corneal copper deposition

Image: “Kayser-Fleischer rings” by Bentham Science Publishers, 2012. License: CC-BY-2.5Clinical presentation of Wilson disease: ABCD