What are the Key Elements of a Patient History?

Taking any patient history begins with what brings the patient in today, better known as a history of present illness (HPI). In general, the HPI is followed by a more comprehensive history, which includes a “chief concern,” past medical history (including chronic illnesses, surgeries, obstetric history, and hospitalizations), family history, social history, medications, allergies, and a “review of systems.” All of these elements comprise the basic pieces of the “history” portion of a history and physical.

FREE Download: Taking a patient history with OLDCARTS

Related videos

What is the History of Present Illness?

The history of present illness, better known by the abbreviation “HPI,” is a summary of the illness that led a patient to seek care, whether in the emergency department, being admitted to the hospital, or coming to an outpatient clinic appointment.

It is meant to be concise, but relatively comprehensive, and can often be the most critical aspect of history taking that aids in making a diagnosis. When taking the HPI, it’s crucial to allow the patient time to explain what happened that led to their presentation in their own words. However, there are a few important elements you should attempt to tease out in order to best characterize a patient’s presenting complaint.

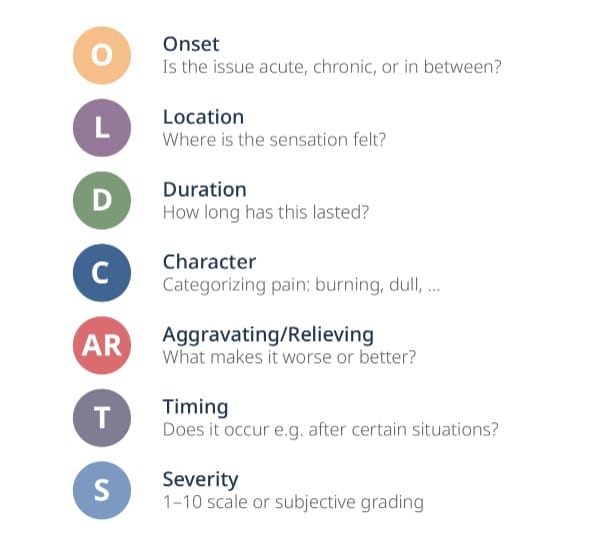

What is OLD CARTS?

OLD CARTS is a common mnemonic used to remember the “key elements” of the HPI. It stands for Onset, Location, Duration, Character, Aggravating/Relieving factors, Timing, and Severity.

Keeping in mind the OLD CARTS mnemonic is a great way to avoid missing crucial information when it comes to the HPI. Frequently, the information you collect from asking the OLD CARTS questions can be enough to lead to a diagnosis!

Onset deals with the start of the patient’s condition. Try to determine whether the problem is new (acute), old (chronic), or somewhere in between. Knowing this can often mean the difference between an emergency and something that can be addressed with routine follow-up.

Location is exactly what it sounds like: where the sensation or pain is felt. Asking about location is most critical for pain-related complaints, but it can also be helpful in certain conditions such as visual symptoms (one eye or both, for instance).

Duration attempts to determine for t how long the condition has lasted. For instance, if the patient has chest pain, has it been constant for hours, or does it come and go for seconds? The difference will help to direct the rest of your history and physical exam.

Character is often used with pain concerns to better categorize the pain. Burning pain might indicate nerve injury, while dull, achy pain might accompany a heart attack.

Aggravating/Relieving factors can be helpful hints to determine what makes a condition better or worse. Shortness of breath that’s worse with exertion might indicate angina.

Timing is another time-related element to help determine when a symptom occurs. For example, stomach pain always felt after eating might have a different cause than before or during eating.

Severity is often graded on a 1-10 scale, but it can also be measured subjectively. An example is a patient who describes the “worst headache of my life” — a classical association with subarachnoid hemorrhage.

What Other Elements are Important to the Patient History?

Although OLD CARTS is a great place to start, you will also need to collect additional information in order to take a comprehensive patient history.

Often, the answers to certain questions in OLD CARTS will prompt additional questions and could blend with other elements of the patient history. For instance, a patient with chest pain may mention that the pain feels similar to a previous heart attack (past medical history), a patient with a rash may mention they were recently prescribed an antibiotic (allergies), or a patient might present with a worsening cough and fever after travel to a foreign country (social history).

Tips for Efficient History Taking

Being fluid but comprehensive in taking a history is a skill that can be more of an art than a science. Although taking a full patient history contains all of the items listed above, you might not always obtain the information listed in that order. Keeping a notecard or list of the elements above can be a helpful aid for ensuring that you are asking all the questions you need to in order to get a full picture of your patient’s health. Here are some other tips for success in history taking:

Ask open-ended questions

Asking a question like “what brings you in today?” can be a great introduction to what’s going on with the patient. Generally, the patient will offer many components of the “OLD CARTS” questions spontaneously when they give an answer to the initial question! This also cuts down on the number of questions you need to ask — spend your time asking clarifying questions based on what they tell you in the initial answer.

Give the patient time to answer

Hand-in-hand with open-ended questioning is the need to give patients plenty of time to respond. One study found that doctors on average interrupt patients in under 23 seconds! A better strategy is to give the patient plenty of time to tell their story before interrupting. This avoids the patient having to repeat themselves and allows you to focus on relevant details and to zero in on important aspects that otherwise can be missed.

Become comfortable with pauses

Sometimes, a patient will need to pause to think about the answer to a question you ask. One useful trick is to count to 10 in your head before interrupting, which will usually prompt the patient to continue their story without getting off track. Pauses are essential to helping the patient devise a narrative that can help you uncover a diagnosis that you otherwise might have missed.

Summarize and reflect what you’ve heard

When the patient is done telling their story, summarize what you’ve heard and reflect it back to them, giving them an opportunity to correct or clarify their history. This serves two purposes: it ensures the information that you’ve gathered is accurate, and it also ensures that the patient feels heard and understood, putting them at ease. Summarizing the possible diagnosis, planned workup, or next steps can also help set expectations for any care to immediately follow the patient interview.

Feel free to return to the patient to ask follow-up or clarifying questions

Sometimes during the course of a patient’s illness, new information, whether from labs, imaging, or other studies, comes to light that can change your framing of the patient’s diagnosis. If a patient is hospitalized, you can always return to the bedside to ask follow-up or clarifying questions in light of new information, or even if you just forgot to ask a question during the initial patient interview.

Don’t forget the “soft skills”

Active listening by nodding, making eye contact, and avoiding distractions such as looking at a computer during the interview can be just as important as the questions you ask during the interview. Learning to read a patient’s body language can be helpful for identifying subtle clues to the patient’s history. This can be particularly important when identifying cases of possible abuse or trauma. It can also be useful for assessing the patient’s emotional state; fear, confusion, or uncertainty can all be identified by non-verbal cues. During the interview, make sure to observe the patient’s body language, as well as what they’re saying directly, to pick up on clues you might otherwise have missed.

Taking a full patient history might seem daunting the first few times you try it. With plenty of practice, it becomes second nature. Keep a list handy of the categories of questions to ask until you get used to history taking, and use the OLD CARTS mnemonic to get yourself started. Before you know it, you’ll be taking a history like a pro!