Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Non-insulin Diabetes Mellitus Medications with Case

-

02-03 Diabetes Mellitus part 1.pdf

-

Reference List Endocrinology.pdf

-

Reference List Diabetes Mellitus.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

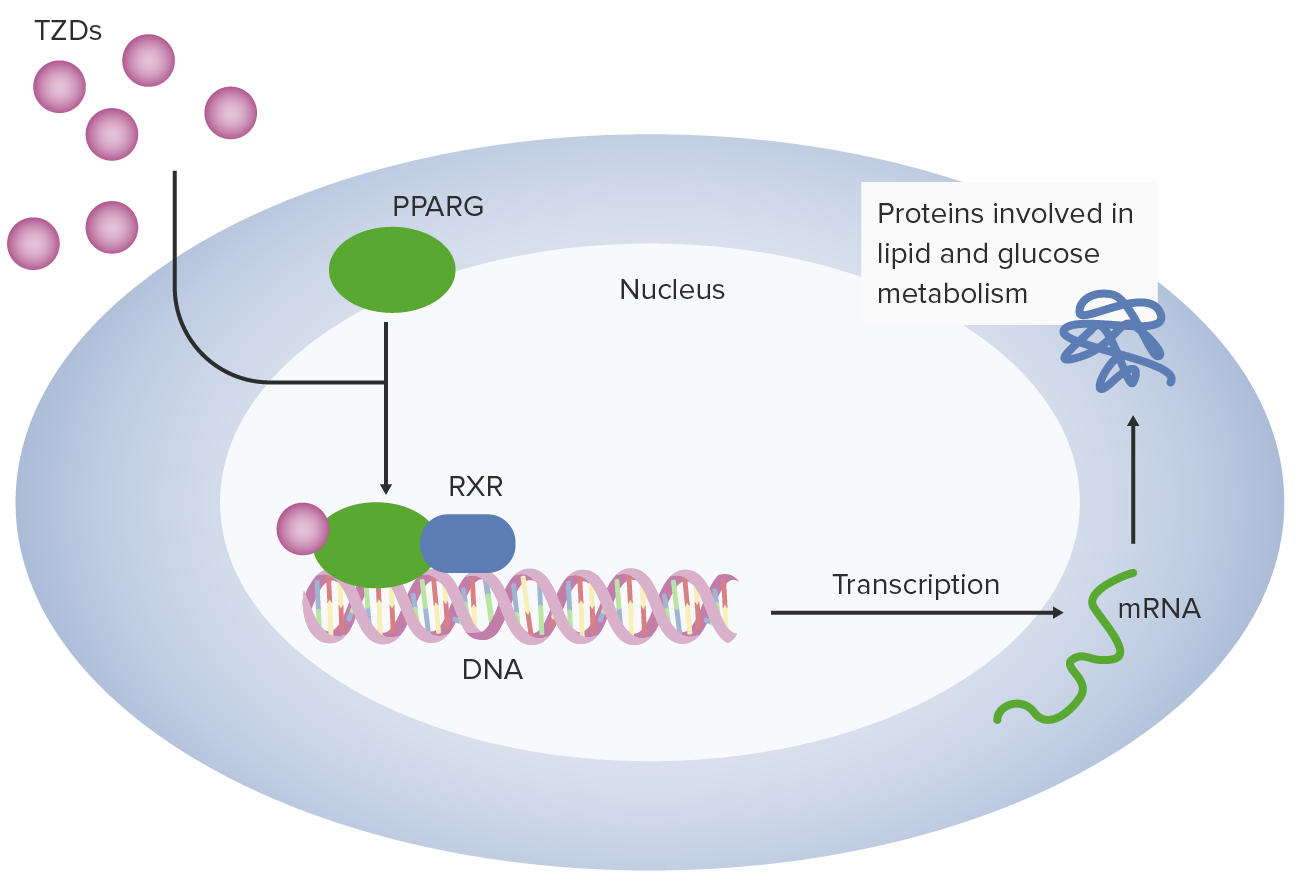

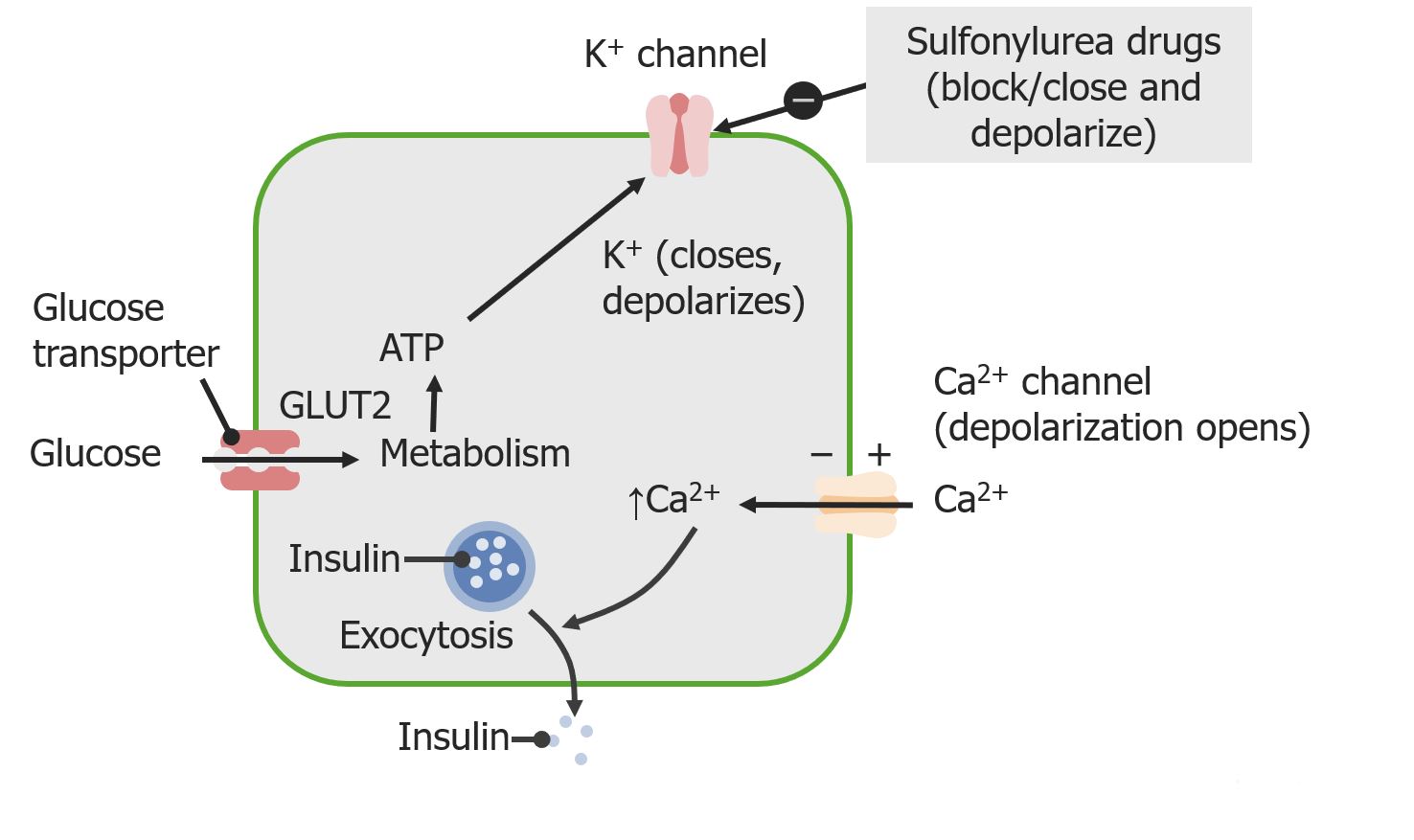

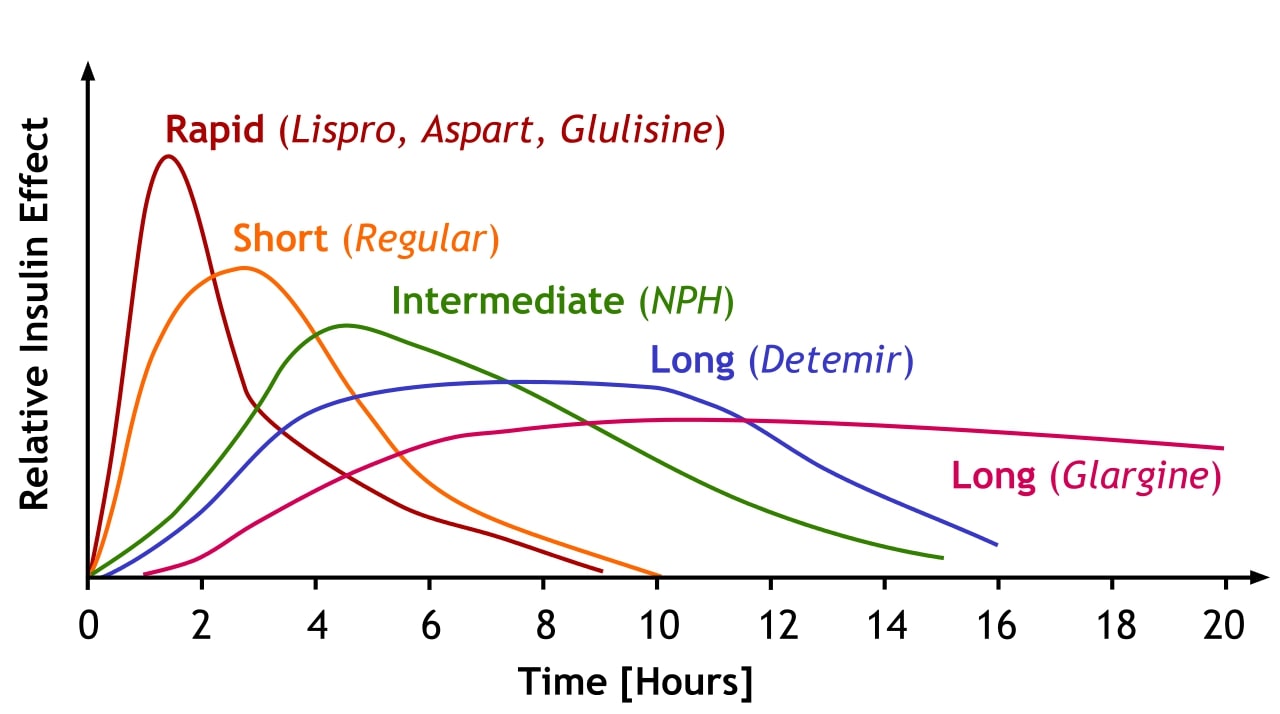

00:01 <b>In this case, a 57-year-old man presents to his primary care physician for follow-up of his</b> <b>diabetes. He has been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 3 months ago and has been started on metformin</b> <b>and lifestyle modifications. The patient does not have any current complaints except for occasional</b> <b>numbness in both hands and feet. His hemoglobin A1c is 8.5% and his serum glucose is 240 mg/dL.</b> <b>What is the best next step for managing this patient? The best next step is to obviously add a</b> <b>second agent to treat his diabetes. Once lifestyle modifications have been initiated and metformin</b> <b>has been started and dose maximized, if the patient continues to have elevations of hemoglobin</b> <b>A1c and serum glucose, a second oral agent is usually indicated. Second line therapy for type 2</b> <b>diabetes after dosing metformin. After initiating metformin, if the hemoglobin A1c remains above</b> <b>goal, the best next step is to add ato add a Glucagon Like Peptide-1 receptor agonist or GLP1RA </b> <b>because there is clinical evidence of neuropathy, a complication of persistent hyperglycemia, which needs urgent A1C improvement. </b> <b>GLP-1 RA also offers the strongest A1C reduction of the second-line agents, </b> <b>it provides cardiovascular protection in a relatively young patient (57 yrs),</b> <b> and is safe to use with a low hypoglycemia risk</b> <b>Let me walk you through the five diabetes medications you'll encounter most often in clinical practice. </b> <b>Everything starts with metformin - it's our foundation and first-line treatment. </b> <b>We love metformin because it's effective, inexpensive, and doesn't cause weight gain. </b> <b>Just remember to start low and go slow to avoid GI upset and keep an eye on the patient's kidney function - </b> <b>you'll need to stop it if the eGFR drops below 30.</b> <b>After metformin, we have some powerful options. </b> <b>The GLP-1 receptor agonists, like semaglutide and dulaglutide, are game-changers. </b> <b>They're especially useful in patients who need weight loss or have underling heart disease.</b> <b> They’re administered as weekly injections, and while they can cause some nausea initially, </b> <b>most patients tolerate them well over time. </b> <b>The main drawback? They're expensive.</b> <b>The Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 or SGLT2 inhibitors, such as empagliflozin and dapagliflozin, </b> <b>are another modern class that's revolutionized diabetes care. </b> <b>These are particularly valuable in patients with heart failure or kidney disease. </b> <b>They work by reducing the reabsorption of filtered glucose and promote urinary glucose excretion in the urine - </b> <b>which means you need to monitor for urinary tract infections, </b> <b>and you can't use them if kidney function is too low (eGFR below 30).</b> <b>Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 or DPP-4 inhibitors, like sitagliptin, are the gentle members of our diabetes arsenal. </b> <b>They're well tolerated, weight-neutral, and less likely to cause hypoglycemia. </b> <b>They are not as powerful as the GLP-1s or SGLT2s.</b> <b> Just use caution with saxagliptin in patients with heart failure.</b> <b>Finally, don't forget about our old friends, the sulfonylureas like glipizide. </b> <b>They're not fancy, but they're inexpensive and effective. The main concerns are weight gain and hypoglycemia,</b> <b> so you will need to counsel patients carefully.</b> <b>The key to success is matching the right drug to the right patient. </b> <b>After metformin, think about your patient's main issue - is it heart disease? Kidney problems?</b> <b>Excessive Weight? Or is cost the biggest barrier? Let that guide your choice of your second agent.</b> <b>That's really all you need to know to get started. Remember, every drug has its place in our toolkit - it's just about using them wisely.</b> <b>it's just about using them wisely.</b> <b>Let's explore further the SGLT2 inhibitors, a fascinating class of medications that has transformed our approach to treating type 2 diabetes. </b> <b>What makes these drugs particularly interesting is that they work in a completely different way from our traditional diabetes medications.</b> <b>Let's start with their unique mechanism of action. Unlike other diabetes medications</b> <b>that work through insulin pathways, SGLT2 inhibitors work on the kidneys by blocking glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubule.</b> <b> This leads to increased glucose excretion in the urine, effectively lowering blood sugar independently of insulin.</b> <b>These medications have proven beneficial in three major clinical areas:</b> <b>First, in Type 2 diabetes, they not only improve glycemic control, lowering A1C by 0.5-0.7%,</b> <b>but also promote weight loss and reduce blood pressure - </b> <b>benefits that are particularly valuable in our diabetic population.</b> <b>Second, and quite remarkably, they've shown significant benefits in heart failure,</b> <b>particularly in patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).</b> <b>What's fascinating is that these benefits occur whether or not the patient has diabetes.</b> <b>Third, they've demonstrated impressive effects in chronic kidney disease,</b> <b>slowing disease progression and reducing cardiovascular mortality, again independent of diabetes status.</b> <b>Among the available medications, empagliflozin, marketed as Jardiance,</b> <b>has shown the strongest cardiovascular outcomes data, -</b> <b>while Farxiga has particularly strong data in heart failure and kidney disease.</b> <b>It's worth noting that while canagliflozin (Invokana) has strong kidney disease data,</b> <b> we need to be cautious about its use due to a slightly higher limb amputation risk.</b> <b>However, we must be mindful of their limitations. These drugs shouldn't be used in </b> <b>patients with severely reduced kidney function (eGFR <30 mL/min),</b> <b>and we need to avoid them in patients with a history of diabetic ketoacidosis.</b> <b>Regular monitoring for UTIs, yeast infections, and avoiding dehydration is essential.</b> <b>Let me tell you about three older diabetes medications that you'll still encounter,</b> <b> though less frequently than our modern options.</b> <b>They're important to understand because you'll see patients taking them, and sometimes they're still useful in specific situations.</b> <b>and sometimes they're still useful in specific situations.</b> <b>First, there's pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione or "TZD." </b> <b>Think of it as the complicated cousin in the diabetes medication family. </b> <b>While it effectively lowers blood sugar, it comes with a lot of baggage - weight gain, fluid retention</b> <b>that can worsen heart failure, risk of bone fractures, and concerns about macular edema.</b> <b>Back in the day, there was also rosiglitazone, but it fell out of favor due to cardiovascular concerns.</b> <b>We still occasionally use pioglitazone, but we're very selective about which patients get it.</b> <b>Then there's acarbose, an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor.</b> <b>It works differently from our other diabetes drugs - it blocks carbohydrate absorption in the intestine.</b> <b>Sounds good in theory, but in practice, it's not very popular in the U.S. </b> <b>Why? It's not very powerful in lowering blood sugar, and it causes a lot of gas and bloating. </b> <b>Patients often vote with their feet on this one and stop taking it.</b> <b>Finally, we have repaglinide, a meglitinide. </b> <b>Think of it as a short-acting cousin of the sulfonylureas.</b> <b>It stimulates insulin release but doesn't last as long in the body. </b> <b>While this shorter action might seem advantageous, it needs to be taken multiple times daily with meals,</b> <b>which isn't great for adherence. Like sulfonylureas, it can cause weight gain and low blood sugar.</b> <b>The bottom line? While these medications aren't first-line choices anymore, they're part of our history,</b> <b>and occasionally, they might be the right choice for specific patients.</b> <b>For instance, if someone can't take any of our preferred agents, or if cost is a major issue,</b> <b>these might become relevant options.</b> <b>That's your quick tour of our "reserve bench” of diabetes medications. </b> <b>Not stars of the show anymore, but still worth knowing about.</b> <b>Let's break down diabetes treatment in a way that's easy to remember for your board exam and on the wards.</b> <b>Every patient with type 2 diabetes starts with the basics: diet, exercise, and diabetes education.</b> <b> Metformin is our foundation medication - we start low at 500mg and gradually increase to 2000mg daily,</b> <b>as long as their kidneys are okay (eGFR should be above 30).</b> <b>Our target A1C is typically less than 7%, and we check it every 3 months.</b> <b>If we're not hitting that target on metformin alone, we add a second drug.</b> <b>This is where it gets interesting - but stay with me, because it's actually pretty straightforward.</b> <b>Choosing the second drug is all about matching it to your patient's main problem.</b> <b>Does your patient have heart disease? Go with a GLP-1 receptor agonist.</b> <b>Heart failure or kidney disease? Choose an SGLT2 inhibitor (as long as their eGFR is above 30).</b> <b>Need weight loss? GLP-1 receptor agonist is your best bet.</b> <b>If cost is the main concern, a sulfonylurea is still a reasonable option.</b> <b>There's one emergency scenario you need to know: </b> <b>if your patient shows up with an A1C above 9% and has symptoms, start both insulin and metformin.</b> <b>Don't worry - you can often transition them to other medications once they're stable.</b> <b>For your exams, remember that these drugs lower A1C differently: </b> <b>GLP-1 receptor agonists and sulfonylureas give you about a 1-1.5% drop,</b> <b>while SGLT2 inhibitors provide a more modest 0.5-0.8% reduction.</b> <b>That's really all there is to it - start with metformin, add a second drug based on your patient's main problem, </b> <b>and adjust as needed. Keep it simple!</b> <b>This is the first of 3 additional challenging board-type clinical cases that highlight different aspects of diabetes management </b> <b>based on renal, cardiovascular, stroke, and all-cause mortality benefits,</b> <b>using the provided algorithm as a guide.</b> <b>In managing diabetes with conditions like chronic kidney disease (CKD) and heart failure,</b> <b>choosing medications that support both glucose control and organ protection is crucial.</b> <b>Let’s review a case to reinforce key decision-making principles in diabetes management,</b> <b>particularly when comorbidities like kidney disease and heart failure are present.</b> <b>Case Summary: A 65-year-old woman with recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes is here for follow-up.</b> <b>Her history includes chronic kidney disease (eGFR 35 mL/min/1.73 m²) and heart failure (NYHA Class II). </b> <b>She has been on metformin, titrated up to 2000 mg/day, and has worked on dietary changes. Her A1c is 8.2%.</b> <b>Which of the following is the most appropriate medication to add for optimal diabetes management?</b> <b>A. Sulfonylurea</b> <b>B. Thiazolidinedione</b> <b>C. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist</b> <b>D. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor</b> <b>E. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor</b> <b>(Pause here to allow time for consideration)</b> <b>The correct answer is D - SGLT-2 inhibitor. </b> <b>In our question about selecting the best add-on diabetes medication for this 65-year-old patient,</b> <b>SGLT-2 inhibitors stand out as the optimal choice. Why? </b> <b>Because they offer a unique combination of benefits targeting both heart failure and chronic kidney disease, which are key concerns in our patient.</b> <b>These medications have proven ability to reduce heart failure hospitalizations</b> <b>and protect kidney function, even in patients with reduced eGFR like our case.</b> <b>Let's quickly review why the other options aren't as suitable:</b> <b>Sulfonylureas, while effective at lowering blood sugar, come with two major drawbacks:</b> <b>hypoglycemia risk and weight gain. Plus, they don't offer any cardiovascular or renal protection.</b> <b>Thiazolidinediones are actually contraindicated in this case. </b> <b>Why? Because they can cause fluid retention, potentially worsening our patient's heart failure.</b> <b>GLP-1 receptor agonists are excellent medications, especially for patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.</b> <b>However, when it comes to heart failure specifically, SGLT-2 inhibitors have shown better benefits.</b> <b>Finally, DPP-4 inhibitors, while safe, simply don't provide the cardiovascular and renal benefits that our patient needs.</b> <b>They're missing an opportunity for organ protection.</b> <b>The key lesson here is that modern diabetes management isn't just about blood sugar control -</b> <b> it's about choosing medications that can address multiple comorbidities simultaneously.</b> <b>For patients with both heart failure and chronic kidney disease, SGLT-2 inhibitors are currently our best option.</b> <b>This next case is a 52-year-old man with type 2 diabetes and a history of ischemic stroke presents for follow-up. </b> <b>He has been on metformin and following lifestyle modifications since his diabetes diagnosis six months ago. </b> <b>His hemoglobin A1c is 8.7%. The patient is asymptomatic and has no other significant medical issues.</b> <b>Which of the following is the best next step in managing this patient’s diabetes?</b> <b>A. Add a sulfonylurea</b> <b>B. Add a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist</b> <b>C. Add an SGLT-2 inhibitor</b> <b>D. Initiate insulin therapy</b> <b>E. Add a thiazolidinedione</b> <b>The optimal medication choice for a patient with a history of ischemic stroke and elevated A1c of 8.7% is answer B:</b> <b>Add a GLP-1 receptor agonist. Let me explain why this is our best choice and then discuss the other options.</b> <b>GLP-1 receptor agonists have emerged as a premier choice for patients with cardiovascular disease, </b> <b>particularly those with a history of stroke. These medications do double duty - </b> <b>they not only provide excellent A1c reduction but also significantly reduce the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events, including stroke.</b> <b>but also significantly reduce the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events, including stroke.</b> <b>Now, let's look at why the other options aren't as suitable. </b> <b>Sulfonylureas, while effective at lowering blood glucose, come with some concerning drawbacks.</b> <b>They can cause both hypoglycemia and weight gain, and importantly, </b> <b>they don't offer any cardiovascular protection - something crucial for our stroke patient.</b> <b>SGLT-2 inhibitors are excellent medications, and they do provide cardiovascular benefits.</b> <b>However, their benefits are particularly strong in heart failure and kidney disease rather than stroke prevention, </b> <b> </b> <b>where GLP-1 RAs have shown superior outcomes.</b> <b>Insulin therapy is a powerful tool for glucose control, but it doesn't offer the cardiovascular benefits we're looking for in this case.</b> <b>We typically reserve insulin for cases requiring rapid glucose control</b> <b>or for symptomatic patients, neither of which applies here.</b> <b>Finally, thiazolidinediones improve insulin sensitivity, but they come with their own concerns -</b> <b>particularly fluid retention, which isn't ideal in patients with cardiovascular histories.</b> <b>They also lack the specific cardiovascular protection our patient needs.</b> <b>The key takeaway here is that in patients with established cardiovascular disease, particularly stroke,</b> <b>we want to choose a medication that goes beyond just glucose control to provide proven cardiovascular benefits.</b> <b>This makes GLP-1 receptor agonists our optimal choice in this scenario.</b> <b>Let's look at this question about managing newly diagnosed diabetes.</b> <b>We have a 63-year-old woman presenting to the ED with classic diabetes symptoms:</b> <b>increased thirst, polyuria, and fatigue. She's showing signs of dehydration but isn't in acute distress.</b> <b>Her labs reveal significant hyperglycemia with a glucose of 485 and A1c of 10.5%, </b> <b>along with mild electrolyte changes and normal kidney function.</b> <b>She doesn’t have any ketones in her urine and her calculated anion gap is normal.</b> <b>This implies that she does not have either diabetic hyperosmolar state or diabetic ketoacidosis.</b> <b>For initial treatment, we're given five options: A. Starting metformin alone</b> <b>B. Using insulin by itself </b> <b> C. Combining metformin with a sulfonylurea</b> <b>D. Start insulin and add metformin prior to hospital discharge</b> <b>E. Starting an SGLT-2 inhibitor with a </b> <b>GLP-1 receptor agonist</b> <b>Let me explain why D - starting insulin and adding metformin before discharge</b> <b> is the correct answer for this patient.</b> <b>This patient's severe hyperglycemia with </b> <b>glucose of 485 and A1c of 10.5%, </b> <b>along with symptoms, she requires </b> <b>immediate, effective intervention.</b> <b>When we see numbers this high with symptoms, </b> <b> we need both rapid control and long-term management.</b> <b>This is exactly what the insulin </b> <b>and metformin combination provides.</b> <b>Let's look at why the other options aren't optimal:</b> <b>Metformin alone, while it's our first-line medication, works too slowly to address this level of hyperglycemia.</b> <b> Using it by itself would leave </b> <b>the patient symptomatic for too long. </b> <b> Insulin alone would work quickly, but we'd miss the opportunity to start metformin,</b> <b>which offers excellent long-term benefits and can help reduce insulin requirements over time.</b> <b>The combination of metformin and sulfonylurea isn't aggressive enough for this degree of hyperglycemia.</b> <b> While both are oral agents, they won't provide the rapid control this patient needs.</b> <b>As for SGLT2-inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists, while they're excellent medications, </b> <b>they're not appropriate as initial therapy for severe hyperglycemia. </b> <b>They work too slowly for this acute situation.</b> <b>Remember: When A1c is above 10% </b> <b>and a patient is symptomatic,</b> <b>combining insulin for immediate control and adding metformin for long-term benefit</b> <b> a few days before the patient leaves </b> <b>the hospital is the best strategy.</b> <b>She would also benefit from teaching </b> <b>by the dietitian and diabetes educator </b> <b>on low carbohydrate diet, how to check</b> <b> her blood glucose and self insulin administration</b>

About the Lecture

The lecture Non-insulin Diabetes Mellitus Medications with Case by Michael Lazarus, MD is from the course Diabetes Mellitus. It contains the following chapters:

- Case 57-year-old Man with Type 2 DM and Numbness

- Non-Insulin DM Medications

Included Quiz Questions

Which schematic best represents the correct order in which to initiate therapies for type 2 diabetes?

- Lifestyle modifications → oral metformin → GLP-1 agonist → insulin

- Lifestyle modifications → SGLT2 antagonist -> oral metformin -> insulin

- Lifestyle modifications → insulin → oral metformin → second oral agent

- Lifestyle modifications → insulin → oral metformin → second injectable agent

- Lifestyle modifications → empagliflozin → oral metformin → insulin

In which of these patients would it be inappropriate to start metformin?

- A 54-year-old man with CKD V

- A 36-year-old woman who had chest CT with contrast two weeks ago

- A 79-year-old man with an HbA1c level of 7.6% who is receiving insulin therapy alone

- A 45-year-old woman with an eGFR of 51

- A 15-year-old boy with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes

Which of the following choices accurately pairs a class of medication with a known side effect?

- Insulin and weight gain

- Metformin and weight gain

- Sulfonylureas and hyperglycemia

- Thiazolidinediones with cardiovascular protection

- GLP-1 agonist with increased risk of UTI

What is the most appropriate next step for treatment of the following patient? A 57-year-old man presents for follow-up of his type 2 diabetes, which was diagnosed 3 months earlier and has been managed with metformin and lifestyle modifications. The patient does not have any current complaints except for occasional numbness in the hands and feet. Laboratory test results: HbA1C level is 8.5%, and serum glucose level is 240 mg/dL.

- Addition of a second oral hypoglycemic agent

- Bariatric surgery

- Switching to a subcutaneous insulin pump

- Increasing the dosage of metformin

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |