Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Seborrheic Dermatitis, Psoriasis and Impetigo in Children

-

Slides CommonRashesinChildren Pediatrics.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

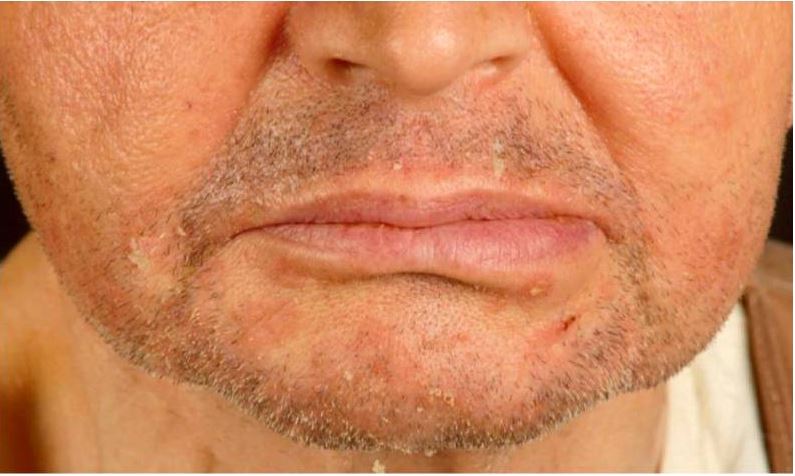

00:00 In this lecture, we will discuss a variety of common pathologic rashes in children. Let's start with seborrheic dermatitis. This is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis. It happens very commonly. It's present in about 5% of the general population and in children often involves areas of high density of sebaceous glands: around the nose, in the ears, wherever there are sebaceous glands. It causes inflammation of the epidermis. It's not a disease of the sebaceous glands themselves. So here is a very classic case of cradle cap. It's remarkably common and it occurs in the first 2 months of life and then again rears its ugly head during adolescence. 00:50 Cradle cap is an erythematous scaly eruption found on the scalp. It's probably bothering the parents more than it is the child. Later, it can spread to flexural areas like under the neck or in the groin or under the armpits. Unlike eczema, this is not very itchy. So in infants it's usually asymptomatic, maybe slightly pruritic. Here's an example of it under this child's neck and then in adolescents it comes back typically as dandruff. Patients can get periocular redness and crusting as well. Patients will have increased sebum production in response to androgens. 01:38 Also, a fungus with perhaps my favorite name of any fungus, <i>Malassezia furfur</i>, will grow in that area. In infants, we can often treat this with simply mineral oil or a little bit of combing. 01:54 In severe cases or in adolescents, we can simply use a dandruff shampoo. We generally treat with emollients so for scales on the scalp we'll give shampoo and combing and maybe ketoconazole shampoo if it's resistant. For body-wide eruptions, we'll treat with mild topical corticosteroids and we may mix with an antifungal such as ketoconazole to kill that <i>Malassezia</i> <i>furfur</i>. Let's skip to another common childhood inflammatory problem which is psoriasis. This is one of the chronic inflammatory dermatoses and it is autoimmune in nature. It's pretty common though. It happens in 1 to 2% of the general population with different forms and different severity. Remember this is an interaction between genes and the environment. So patients with HLA type C particularly HLA-Cw*0602 are going to have an increased risk of psoriasis and homozygotes have an even further 2-1/2 times higher risk than the heterozygotes. Psoriasis is generally a well-demarcated erythematous papular lesion with plaques and it has a silvery scale to it mainly on extensor surfaces. The clinical presentation is diagnostic. They will have itching, they will generally have a bilateral distribution and you may see nail pitting on their nail exams. These are all findings of psoriasis. Psoriasis is generally triggered by some sort of problem. A patient has an underlying risk for it and then they have flares. An example would be minor trauma, upper respiratory infections, stress, cold, low sunlight levels so sunlight helps and some medications. If you will look pathologically, you would notice an epidermal hyperplasia and perakeratotic scale. These patients have accumulation of neutrophils within the superficial epidermis. When we see these patients, we recommend avoiding rubbing or scratching because remember minor trauma makes it worse and we give them emollients or moisturizers. Sunlight exposure helps. Tar preparations will help and we can put them on topical steroids or vitamin D analogs. We'll move on to another common infection in skin and this is impetigo. We see this a lot in children. This is a common superficial bacterial infection of the skin and it's usually caused by group A <i>Strep</i> or <i>Staphylococcus</i>. It's highly contagious and usually starts on the face and the hands and then spreads. Patients classically have a honey-colored crusted lesion. 05:02 Moving on, there is a more significant bacterial infection that can incur in children which is bullous impetigo. Bullous impetigo is also caused by <i>Staph</i> and group A <i>Strep</i>. We see it more commonly in people with less vigorous bathing. It causes flaccid, thin-walled bullae or tender shallow lesions surrounded by the remains of the blister roof that often pops. This is commonly implicated in <i>Staph</i> scalded-skin syndrome. Patients with impetigo have bacteria in their epidermis that evoked innate humoral response. They suffer epidermal injury and they have local serous exudate, not pustule, which forms a scale or a crust. These patients will have accumulation of neutrophils beneath their stratum corneum. The pathogenesis of blister formation is somewhat interesting. Basically, the bacteria produce a toxin, the toxin cleaves desmoglein 1. Desmoglein 1 is responsible for cell-to-cell adhesion. With that breakdown of cell-to-cell adhesion, these bullae can now form in the upper epidermal layers. How do we treat impetigo? Well, untreated lesions usually last 2 to 3 weeks and then generally resolve but we can gently remove the crust to prevent spread and then we'll provide topical antibiotics such as mupirocin which is very effective against <i>Staph</i> and group A <i>Strep</i>. We may, in severe cases, also provide oral antibiotics such as a 1st generation cephalosporin, cephalexin, which can be given twice a day in cellulitis or clindamycin if we're suspecting MRSA or there is invasive disease. Remember, these lesions heal without scarring and generally these patients do well. So that's a summary of a few common infections or skin findings in children. 07:06 Thanks for your time.

About the Lecture

The lecture Seborrheic Dermatitis, Psoriasis and Impetigo in Children by Brian Alverson, MD is from the course Pediatric Dermatology. It contains the following chapters:

- Common Rashes in Children

- Psoriasis

- Impetigo

Included Quiz Questions

Which of the following statements is TRUE about psoriasis?

- The mainstay of treatment for mild disease is topical steroids.

- There is no genetic predisposition.

- Presentation is typically unilateral.

- Nail involvement is a rare finding.

- The course is constant without flare-ups.

Which of the following is NOT a clinical feature of seborrheic dermatitis?

- Severe pruritus

- Occurs in skin areas rich in sebaceous glands

- Inflammation of the epidermis

- Cradle cap

- Involvement of inframammary fold

Which of the following organisms has been associated with seborrheic dermatitis?

- Malassezia furfur

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Candida albicans

- Staphylococcus epidermidis

- Herpes simplex virus

Which of the following is NOT recommended in patients with psoriasis?

- Rubbing

- Vitamin D supplements

- Sunlight exposure

- Topical steroids

- Emollients

Which of the following is not a trigger of psoriasis?

- Sunshine

- Upper respiratory tract infection

- Trauma

- Cold weather

- Stress

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

2 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

Great idea to group these diseases together and clear clinical pictures!

Nice summary of most common rashes in children. Nice recap questions.