Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

IE Management: Antibiotic Treatment

-

Slides InfectiveEndocarditis InfectiousDiseases.pdf

-

Reference List Infectious Diseases.pdf

-

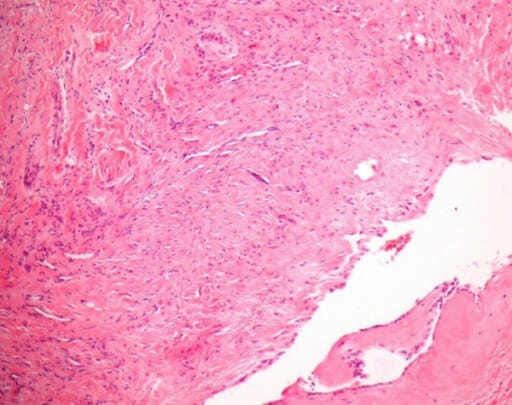

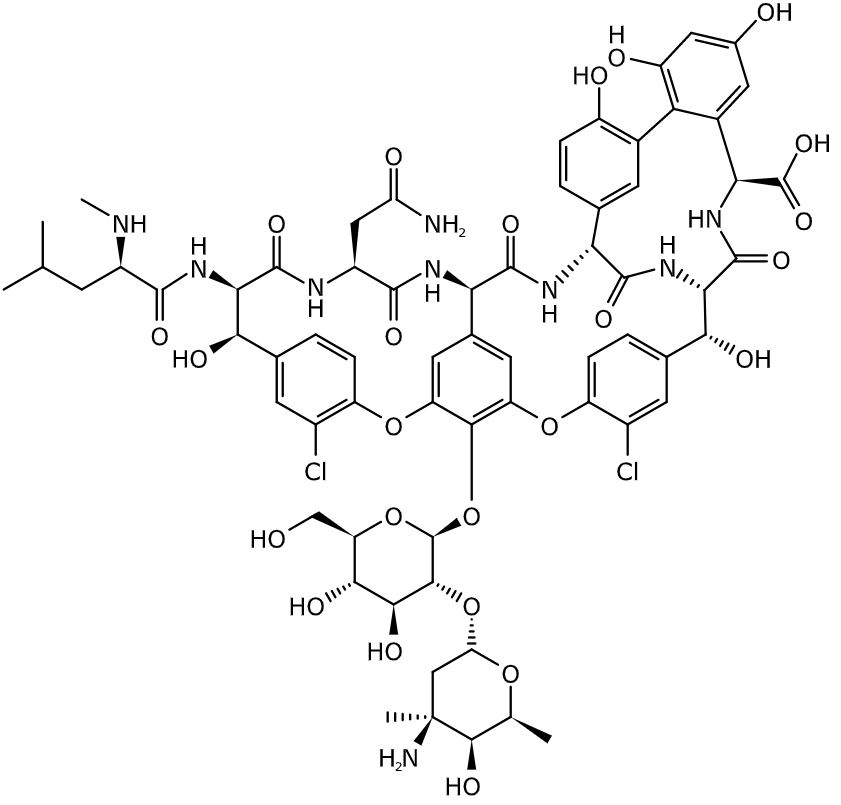

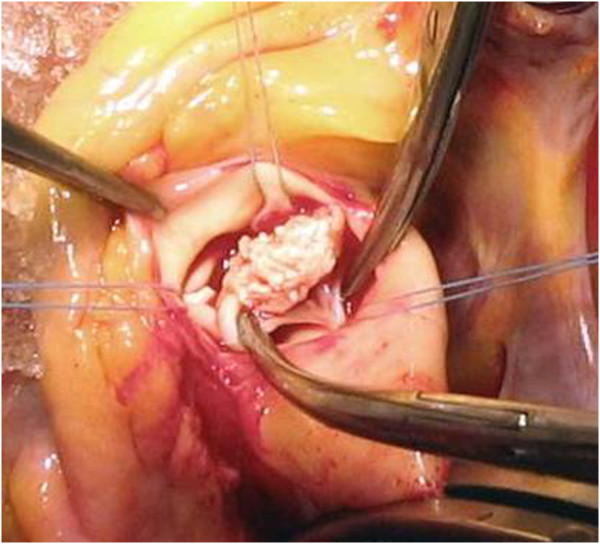

Download Lecture Overview

00:00 What do you treat a patient who’s got a penicillin susceptible oral strep or group D strep with a low MIC? What’s recommended is either a four-week regimen or a two-week regimen. The four-week regimen is going to include penicillin in high doses. Let me stop there and tell you why. You don’t want to give a moderate dose of an antibiotic in any serious infection. As we say, “Send a man to buy the beer.” Jack up the dose to high dose because these vegetations, some of these bugs are deep within the vegetation. 00:45 You literally have to soak the vegetation in high doses of antibiotics to get the penetration into it. 00:53 You’d hate to use a moderate dose of an antibiotic and have the patient fail. You’d have to ask yourself, “Well, did they fail because I didn’t give them enough antibiotic?” When you’re treating serious infections, endocarditis and other serious ones, maximize the dose. Give the maximum dose allowable for that patient. That’s a good infectious disease strategy for many diseases. If they can’t take penicillin G, ceftriaxone is okay. Now, the two-week regimen has got a little addition to it. 01:28 The two-week regimen calls for high dose penicillin or ceftriaxone. But if you’ll notice, gentamicin is added for synergism. There are some patients who aren’t that sick that you could actually consider a two-week regimen. Most of them are going to get longer therapy but a two-weeker is okay. 01:52 Now, what if you have a relatively resistant organism and with the MIC a little higher? You’re out with the two-week regimen. You’re going to have to give essentially a four-week regimen. 02:09 In β-lactam allergic patients, you’re going to have to use vancomycin. Now, what if you have native valve Staph aureus endocarditis? Remember Staph aureus is a very aggressive organism. 02:31 Let’s say it’s methicillin-susceptible Staph aureus. I’m fine with high dose oxacillin or nafcillin. 02:41 What’s recommended currently is four to six weeks of IV therapy. Some of that can be given at home. 02:47 For MRSA, vancomycin 4-6 weeks is OK. 02:50 For enterococcus, the current recommendation is ampicillin 12gms/d + ceftriaxone 2 g intravenous for 6 weeks MRSA or in a penicillin-allergic patient, you're going to be using vancomycin in high dose for the same duration. 03:10 In an effort to address both antibiotic resistance and complications from prolonged hospitalization, there's growing interest in reducing IV antibiotic duration for carefully selected IE patients. 03:22 We know extended IV therapy carries risks - line infections, DVTs, PICC line complications - so we need to carefully consider when oral antibiotics might be appropriate. 03:35 Patient selection is critical. We need to identify individuals who have been clinically stable for over 10 days, have definitively cleared their blood cultures, and have no indication for surgical intervention. 03:49 These patients must be able to absorb oral medications reliably and be trusted to take their pills consistently. 03:56 Additionally, their infecting organisms must be susceptible to available oral options. The timing of the switch is also crucial. 04:05 We typically consider this after 2-3 weeks of IV therapy, and only in uncomplicated cases where we can ensure close follow-up. 04:13 It's important to understand that this approach is appropriate for only about 20% of IE patients. 04:21 The standard of care remains IV therapy - this is a specialized option for select cases, not a replacement for traditional treatment. 04:31 Given the complexity of this decision, always obtain an ID consultation before making the switch, and ensure you have a solid monitoring plan in place. 04:41 This targeted approach to oral step-down therapy represents a careful balance between reducing unnecessary complications from prolonged IV access while maintaining effective treatment of this serious infection. Let’s say you’ve got prosthetic valve Staph aureus endocarditis. If it’s methicillin-susceptible then you’re going to use oxacillin or nafcillin plus rifampin plus gentamicin for the first two weeks. If it’s methicillin-resistant, it’ll be vancomycin plus rifampin plus gentamicin for the first two weeks. The duration of therapy is six or more weeks. So, how do you know whether the patient is cured? Well, you’re going to have to stop antibiotics at say, the six-week mark. Wait until the antibiotics clear from the system and then redraw the blood cultures. If the blood cultures are positive, you didn’t treat long enough. 05:56 The ampicillin-ceftriaxone combination has become a standard treatment option for enterococcal endocarditis, particularly for E. faecalis infections. 06:06 This regimen is especially valuable for treating aminoglycoside-resistant strains or in patients who cannot tolerate aminoglycosides. 06:15 The only downside is if they’re β-lactam-allergic then you’ve really got to come up with some kind of concoction. 06:25 What they recommend is linezolid or daptomycin, all sorts of things. So, you don’t want your patient to have enterococcal endocarditis particularly one that’s resistant to the aminoglycosides. 06:41 The duration of therapy is going to be at least and probably more than six weeks. 06:49 Let's talk about surgery. 06:51 The approach to surgical timing has evolved significantly.c Historically, surgeons preferred completing a full course of antibiotics before valve surgery. 07:01 However, this approach proved problematic because patients can deteriorate rapidly while on treatment - a prosthetic valve might dehisce, or patients might suffer embolic events to the brain. 07:14 Numerous studies now support early surgery - meaning during the initial hospitalization - for reducing both mortality and morbidity in selected patients. 07:25 The main indications for early surgery include patients with congestive heart failure from severe valve dysfunction, and cases of uncontrolled infection - when you've got the right antibiotic but blood cultures remain positive, suggesting a focus around the valve that's shedding organisms into the bloodstream. 07:45 We're also concerned about patients who develop heart block, as this suggests an aortic valve annular abscess involving the conduction system. Other key indications include the presence of metastatic abscesses, and large vegetations that have already embolized or are at high risk of doing so. 08:06 Additionally, certain pathogens themselves can be an indication for early surgery - particularly difficult-to-treat organisms such as fungi, gram-negative rods, or multi-drug resistant organisms like some enterococci. 08:22 The key point is that while completing antibiotics before surgery sounds nice in theory, waiting can be dangerous. 08:30 These complications can develop precipitously, so there’s been a clear movement toward earlier rather than delayed surgical intervention in high-risk cases. 08:41 How about the mortality of infective endocarditis? It’s substantial, 15% to 22% die in the hospital. 08:49 The five-year mortality approaches 40%. It’s less for right-sided infective endocarditis or left-sided native valve due to α-strep. It’s less than 10%, so a good outlook for those patients. 09:06 But look what it is for Staph aureus on a prosthetic valve, greater than 40%. So, there are really several groups of persons who are at risk for mortality from endocarditis. These include higher age, heart failure, someone who’s had a stroke or other embolic event, and then endocarditis that develops in association with healthcare. In other words, the patient has had some severe problem otherwise leading to them getting infective endocarditis.

About the Lecture

The lecture IE Management: Antibiotic Treatment by John Fisher, MD is from the course Cardiovascular Infections.

Included Quiz Questions

A 65-year-old man is diagnosed with native valve enterococcal endocarditis. With an aminoglycoside-sensitive infection, which of the following regimens is most appropriate?

- Ampicillin + gentamicin

- Penicillin G + ampicillin

- Vancomycin + gentamicin

- Vancomycin + ampicillin

- Ceftriaxone + vancomycin

What is the recommended duration of treatment for Staphylococcus aureus native valve endocarditis?

- 6 weeks of intravenous therapy

- 6 weeks of oral therapy

- 2 weeks of intravenous therapy

- 4 weeks of combined oral and intravenous therapy

- 6 months of intravenous therapy

Which of the following is the most appropriate antibiotic regimen for the treatment of native valve endocarditis due to methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)?

- Vancomycin

- Vancomycin + gentamicin

- Nafcillin + gentamicin

- Ampicillin + gentamicin

- Vancomycin + ceftriaxone

Which of the following is NOT an indication for cardiac surgical treatment in patients with endocarditis?

- New or worsening cardiac murmur

- Congestive heart failure

- Lack of effective antimicrobial therapy

- Embolic stroke

- Partially dehisced unstable prosthetic valve

Which of the following patients has the highest risk of mortality from infective endocarditis?

- A 70-year-old with baseline congestive heart failure who develops Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic valve infective endocarditis

- A 28-year-old intravenous drug user with right sided infective endocarditis

- An otherwise healthy 35-year-old with Enterococcus infective endocarditis

- An otherwise healthy 70-year-old with native valve Streptococcus viridans infective endocarditis

- An asthmatic 50-year-old with endocarditis by a fastidious organism

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |