Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT) – Interventional Studies (Study Designs)

-

Slides 08 InterventionalStudies Epidemiology.pdf

-

Reference List Epidemiology and Biostatistics.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

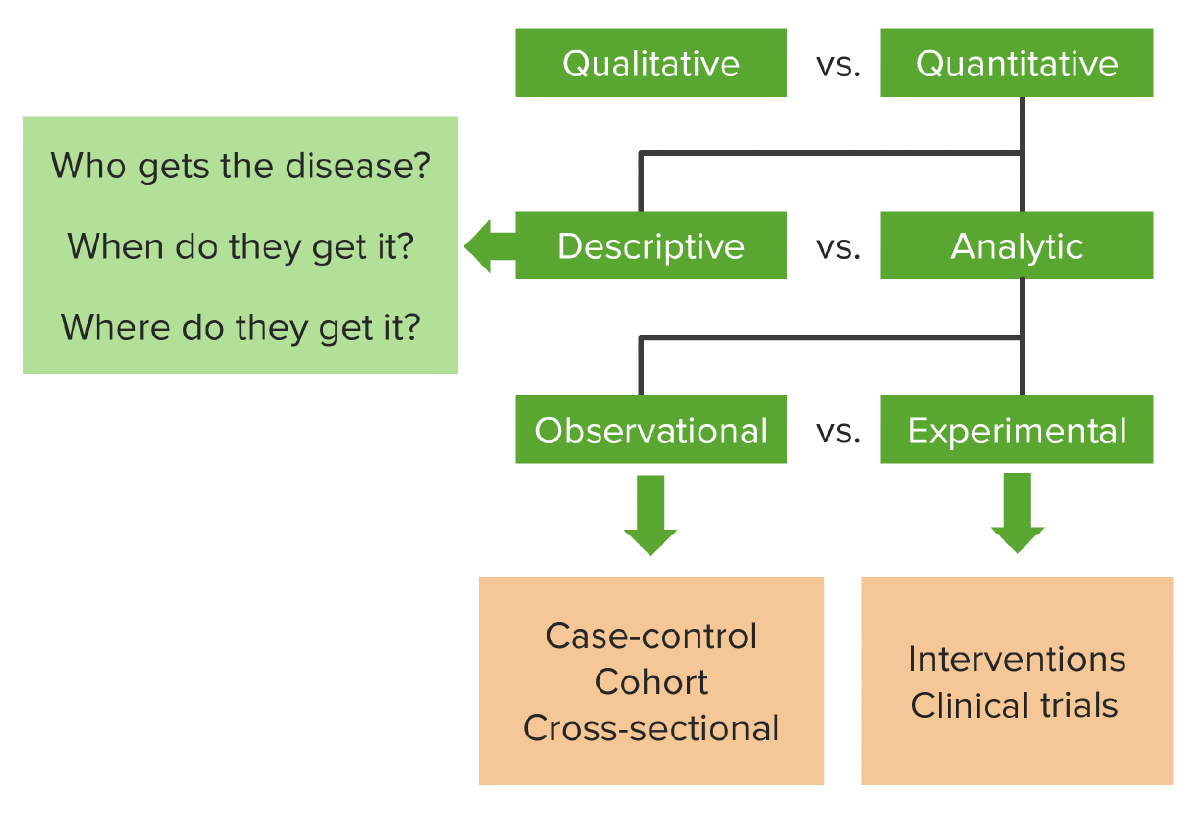

00:01 Hello and welcome to epidemiology. Today we're going to look at what I think is your favorite study design. I think so because it's probably the most famous study design, the most important one and definitely the most expensive one. It's the foundation of drug delivery. It's the randomized controlled trial or randomized clinical trial or RCT. It's a kind of experiment. 00:21 In fact we'll be talking about all kinds of experiments in this lecture. After this lecture, you're going to know the characteristics of a randomized controlled trial or RCT. You're going to know why some RCTs are blinded. You'll know what that means after today as well. 00:36 You're going to know the characteristics of a quasi-experiment, which is like an experiment but not quite. You're going to know the characteristics of what's called a natural experiment and about something called an ecological study, which may or may not be an experiment, but we'd like to talk about it in the same breath as experiments. 00:55 So a randomized controlled trial is a kind of a experiment, it's also the gold standard for evidence. We like to use that term a lot, gold standard. Iit's our best test for evidence in terms of causality, does this cause that, does an exposure cause an outcome, does a drug actually cause a change in the patient. It's the highest form of proof that one thing causes another and pretty much every approved drug or treatment or therapy or technology on the market has gone through at least one rigorous round of RCT testing before the government allows it onto the marketplace. So today in this lecture, we're going to cover where experiments fit onto the big map of study designs that we keep going back to. We're going to look at the basic design of an RCT, which is of the best kind of experiment for epidemiological purposes. We're going to look at how an RCT differs from a case-control study, even though they use the same words. We're going to look at the advantages and disadvantages of an RCT, because even though it's pretty good as a study design, it has got some bad parts to it as well. And we're going to talk about why it is the 'R' exists in RCT, why you randomize, have you given this some thought? Why do we prefer this thing called blinding, I want you to think about that as well and we're going to find some answers together. And we're going to look at the design of this thing called a quasi-experiment which resembles our RCT, but is lacking one important characteristic, the 'R', the randomization part. We're also going to spend some time to talk about the difference between an internal and an external validity, both kinds of validity, but distinctly different from each other. And we're going to look at something called a natural experiment as well as, as I mentioned, an ecological study. 02:43 So where does an RCT fit onto our grand map of study designs? As you recall, the universe of research is divided into qualitative and quantitative research. Qualitative are things like interviews and focus groups. Quantitative is when we use numbers and statistics. 03:01 The world of quantitative research is divided into descriptive and analytical research. 03:06 Descriptive research is when we describe something, the who, what, where, when, never the why, of something going on, usually with one variable in mind. When we do an analytical study, we're comparing or drawing associations between two or more variables. And there are two kinds of analytical studies, observational and experimental, do you remember what other kinds of observational studies there are? I'll help you, there's a case control, there's a cohort and sometimes there's a cross-sectional as well. There are other types as well, but those are our three main ones. In the world of experimental studies though, we have the RCT, that's our favorite go to experiment in. It's an interventional clinical trial. So, the RCT, as I mentioned, is the only method that we understand that offers undeniable proof that something causes something else. It is the gold standard for determining causality. We use it to measure usually the efficacy of new drugs, that's why RCTs are mostly conducted by drug companies, probably because they have a vested interest in measuring the efficacy of their products, also because RCTs are enormously expensive to do well and only drug companies and governments tend to be wealthy enough to do good ones and large ones well. So RCTs are study designs that can be used for evaluating a variety of different things, usually approaches to treatment and prevention. Is this treatment better than nothing, or better than the existing standard, or better than a placebo, or better than some other kind of therapy? We use it in the clinical setting, or in the community setting. A lot of people haven't thought about that. Can you think of some examples when an RCT is appropriate for a non-clinical setting, a non-drug trial, a non-biotech trial, a non-intervention? It can be used in a community; perhaps you're testing the differences in educational interventions or government policies. The design is applicable to a variety of scenarios, not just medical scenarios. So RCTs are used to evaluate new drugs and treatments, they're used to assess new programs and they're used to determine new ways of organizing and delivering healthcare even. Again, we can just randomize people under a variety of different paths and compare them after randomization. So let's go back to the question that I'd like to bring all my study designs back to, is there an association between smoking and lung cancer? Smoking is exposure, lung cancer is the outcome. In an RCT design, this is how we'd approach this. We have a defined population, maybe adults living in this country and we choose some of them and we randomize that sample into two groups, some will be smokers and some will be non-smokers. They don't get to choose. I get to choose. 05:54 I'm the researcher. I'm the investigator, I've randomized them. I make this motion because that's a coin flip. That's the most basic kind of randomization, flip a coin, heads you smoke, tails you don't smoke. So I'm deciding the exposure that you get. After you're exposed, we wait some time and we see which group gets what outcome. If it's a drug trial, we're seeing which group has more people improve from the disease versus the other group, if it's smoking and lung cancer, we're looking to see the prevalence or incidents rather, of lung cancer in both of the groups and comparing the two. The key there is the randomization. 06:31 Now it sounds similar to a case-control study right, because we have cases with people who get diseases or the people that we're going to get the intervention, they have controls of people who don't, case-controls uses the same words, but in RCT it is quite distinct from a case-control study. A case-control you may recall from our lecture on observational studies, begins by ascertaining the outcome, deciding who got a disease and who didn't and then looking backwards in time to see what the exposure was. An RCT is quite different, we look forwards in time, first of all its prospective and also I, the researcher, decide who gets what exposure. Now because it's prospective it also resembles a cohort design, but it is distinct from a cohort design because cohort designs, the world unfolds as it will, we simply observe the outcome, we don't get to choose who gets what exposure, they choose themselves. In an RCT we, the investigators, we choose who gets what. So the basic design again, we have our study population, individuals we've recruited to be a part of our study, we randomize them into two groups. Study A, gets the treatment, maybe it's a drug, usually is. Study B, doesn't get the treatment, they are the control group. They're either getting nothing, they're getting the current therapy that's different from the therapy I'm testing, or they're getting something called a placebo, which we will talk about in a bit. You know what a placebo is already I bet, but we're going to talk about it a bit more anyway.

About the Lecture

The lecture Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT) – Interventional Studies (Study Designs) by Raywat Deonandan, PhD is from the course Types of Studies.

Included Quiz Questions

What characteristic is missing in a quasi-experiment that differentiates it from a randomized control trial?

- Randomization

- Intervention

- External validity

- Control group

- Blinding

Which of the following MUST be included when designing an RCT?

- Prospective design

- Placebo group

- Physician

- Disease of interest

- All of the above

Which of the following studies are considered the "gold standard" for evidence for causality?

- Randomized control trials

- Case-control

- Cohort

- Cross-sectional

- Focus group

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

1 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

a very helpful and good lecture. the way of explanation is amazing