Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV): Definition and Pathology

-

Slides HumanImmunodeficiencyVirus InfectiousDiseases.pdf

-

Reference List Infectious Diseases.pdf

-

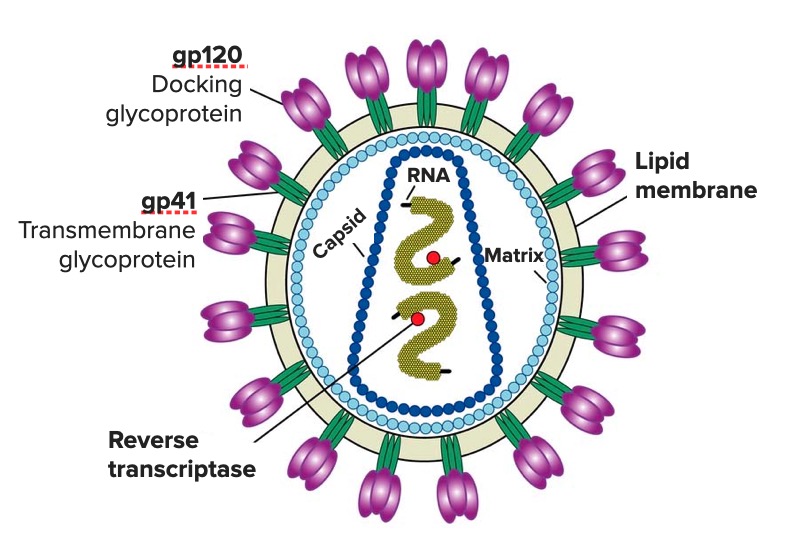

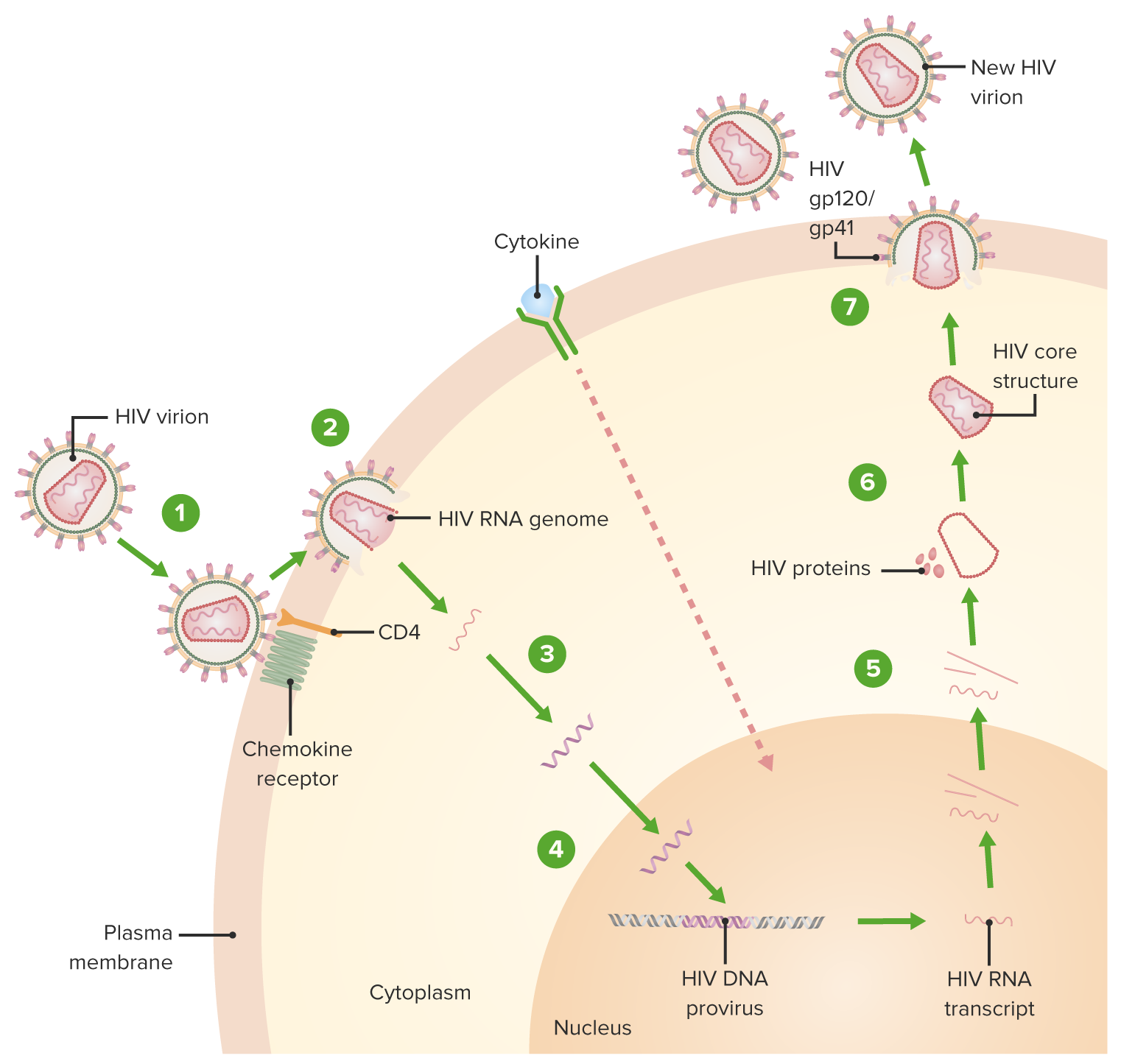

Download Lecture Overview

00:01 We continue our discussion of sexually transmitted infections with the human immunodeficiency virus. 00:14 HIV infection is a sexually transmitted or blood-borne retroviral infection characterized by gradual decline and cell-mediated immune function, and complicated by a wide variety of opportunistic microbial infections and cancers. 00:35 As you can see from this global map, the prevalence of HIV infection is definitely worldwide and notice the heavy concentration in Southern Africa. 00:51 In certain countries in Southern Africa, approximately one in every 4 to 5 people you meet is HIV-positive. 01:05 This is a predominantly sexually transmitted infection among heterosexuals, among men who have sex with men, and among bisexuals. 01:15 And there is an alarming increase in infections among black women. 01:23 Persons with intravenous drug use comprise about 7 percent of the infections. 01:29 In 2011, there were 34 million persons infected, in approximately in equal ratio between males and females. 01:39 More than two-thirds of HIV infections worldwide are in sub-Saharan Africa. 01:47 And there, it is primarily a heterosexual transmission problem because homosexuality is a taboo in many African countries. 01:58 It can also be spread to innocent victims like mother to child. 02:04 Pregnant women can spread it to their babies, either in utero, at delivery, or through breastfeeding after delivery. 02:14 Let’s talk a little bit about the virus itself. 02:19 HIV is an RNA retrovirus. 02:26 And what that means is that it is capable, once getting into a target cell, of making a DNA copy of itself. 02:40 It kind of goes retrograde from RNA to DNA. 02:46 We’ll talk more about how that happens shortly. 02:51 And there are essentially two types of the human immunodeficiency virus. 02:58 HIV1 is actually closely related to a chimpanzee simian immunodeficiency virus, SIV. 03:09 Within Group M, which is responsible for the global pandemic, we've identified nine distinct subtypes, labeled A through K (excluding E and I). Each of these subtypes is unique, with distinct geographic distributions and genetic characteristics. 03:27 Understanding these subtypes is crucial for tracking the epidemic and developing effective treatments. 03:34 Now, let's turn to HIV-2, which has a different story. 03:38 Like HIV-1, it originated from a simian immunodeficiency virus, but its primarily confined to West Africa. 03:46 While HIV-2 has eight groups, labeled A through H, only groups A and B have actually achieved sustained transmission among human populations. The other groups, C through H, represent what we call dead-end infections - they've only been identified in single individuals and haven't shown any evidence of further spread. 04:09 HIV-2 has several important distinctions from HIV-1: it has never caused a pandemic, mother-to-infant transmission is extremely rare, and importantly, most people infected with HIV-2 don't progress to AIDS. 04:25 And although some patients can get AIDS with HIV2, most do not progress to AIDS. 04:33 And I want you to focus on this cartoon of the virus. 04:39 And I think you can see that it has some spikes on the circumference. 04:45 These are in virology terminology called peplomers, and notice that they are comprised of glycoproteins – gp120 and gp41. 05:02 gp120 is the outermost glycoprotein and it is what helps the virus dock with the target cell. 05:15 gp41 is the part that actually fuses to the human cell membrane - keep that in mind. 05:30 Inside the virus, you have two copies of the viral RNA. 05:35 And the little red dot signifies an important enzyme known as reverse transcriptase. 05:45 It is this enzyme, which enables the virus to make a DNA copy of itself. 05:52 This infection is transmitted primarily person to person through sex, but it also can occur from mother to child during delivery and contact with the blood of an infected person. 06:07 The exact cell type that is infected first is unclear. 06:12 What seems to happen is that there’s a break in the genital mucosa, a break in the skin, and then the virus infects a dendritic cell, which then is carried to other cells that have this molecule, called the CD4 molecule. 06:32 Examples of cells that have that are the macrophage, T helper cells, and that’s necessary but not sufficient. 06:42 In other words, the virus can attach to this CD4 molecule, but it needs something else, and that is a chemokime receptor. 06:50 And the chemokime receptors are the way that white cells essentially talk to one another. 06:58 We’re talking here about CCR5 and CXCR4. 07:03 These are two chemokime receptors that determine whether the virus is going to enter the cell. 07:10 So what happens is these outer glycoprotein, gp120, docks with the CD4 molecule and a chemokime receptor, either CCR5 or CXCR4. 07:24 And once it attaches to those chemokime receptors, there’s a twist – a conformational change exposing this fusion domain, which is present on gp41, and that allows the HIV membrane to fuse with the human cell membrane. 07:45 And that is the way that the virus gets into the cell after it fuses. 07:50 So there is a class of drugs that actually can block at this step called fusion inhibitors. 07:59 Anyway, once the virus gets into the cell, it’s got to uncoat. 08:05 And it uncoat and unloads its two copies of positive-sense RNA, and this is where the HIV reverse transcriptase kicks in. 08:17 It makes a DNA copy of itself, and now it's viral DNA, and that is what integrates into the cell chromosome. 08:27 That’s what gets into our DNA. 08:31 And so, reverse transcriptase inhibitors are going to block this retroviral change from RNA to DNA. 08:47 Now, human DNA is then integrated into the human chromosome. 08:52 It gets into our DNA, and this is where integrase inhibitors work. 08:59 Then HIV DNA starts making its own messenger RNA at our ribosomes. 09:06 It kind of commandeers our ribosomes and makes the components of new HIV. 09:15 And then the new HIV virions emerge from an infected cell, and initially they are immature. 09:24 And then they become mature, and this is where protease inhibitors prevent this maturation step. 09:32 Protease inhibitors, as you know, are one of the important forms of antiviral chemotherapy. 09:40 And the cells die as a result of this infection. 09:45 And they die in enormous numbers – tenth to the ninth CD4 T-cells are killed by this virus every day. 09:54 And as the virus is released from a CD4 cell, it attacks new CD4 T-cells.

About the Lecture

The lecture Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV): Definition and Pathology by John Fisher, MD is from the course Genital and Sexually Transmitted Infections. It contains the following chapters:

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) – Definition

- HIV – Pathology

Included Quiz Questions

Which of the following geographic locations has the highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS?

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- South America

- Western United States

- West Africa

- South Asia

Which of the following HIV strains/groups is responsible for the worldwide AIDS pandemic?

- HIV-1 group M

- HIV-1 group O

- HIV-1 group P

- HIV-1 group N

- HIV-2

Which of the following best describes the function of the HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120?

- It mediates docking of the viral envelope with the target cell membrane.

- It mediates fusion of the viral envelope with the target cell membrane by binding to CD8 and a chemokine receptor.

- It prevents fusion of the viral envelope with the target cell membrane by blocking CD8.

- It prevents fusion of the viral envelope with the target cell membrane by blocking CD4.

- It mediates fusion of the viral envelope with the target cell membrane by binding to B cells.

What is the main mechanism of action of HIV fusion inhibitors?

- Binding HIV glycoprotein 41

- Binding HIV glycoprotein 120

- Binding host membrane glycoprotein 41

- Binding host membrane glycoprotein 120

- Binding both glycoprotein 41 and glycoprotein 120

Which of the following enzymes copies the HIV positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome into a complementary DNA molecule?

- Retroviral reverse transcriptase

- Host cell reverse transcriptase

- Retroviral helicase

- Host cell helicase

- Host cell DNA ligase

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

3 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

this is a super brilliant lecture, vey pedagogic and complete

Really well explained. informative and detailed whilst also being concise

Absolutely my favorite lecture so far! It was really informative, yet left me craving more. The way you explained it was easy to understand (I am a pre-nursing student). Thank you and great job!