Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Groups – Interventional Studies (Study Designs)

-

Slides 08 InterventionalStudies Epidemiology.pdf

-

Reference List Epidemiology and Biostatistics.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

00:00 Okay, now when we do a randomized controlled trial something often happens, that is, people might change from one group to another, you can probably imagine a scenario where that might be the case. So I've allocated my subjects to either the treatment group or the control group. Something might arise, maybe someone is responding in a different way, maybe I misjudged their therapeutic state or something like this and I have to change which group they're in. It doesn't happen a lot, it does happen occasionally. Now when they change group, what do I do about it, I have some options; I can either remove that person from my analysis entirely or I could pretend they were always in the group they ended up in or I could pretend they're still in the group they started in, which is better? Well if we eliminate the individuals who move, what happens is we introduce a kind of bias here, because why did they move? Maybe they moved because they're responding differently, a number of scenarios comes to mind. So we don't want to introduce any kind of bias, we like to keep our subjects in the study as much as we can, so that's not an option. If we analyze them according to the treatment that they received, for example, maybe they started out in the control group but they moved to the treatment group and now I'm going to analyze them with everyone else who was in the treatment group. Well that biases my analysis in favor of finding a difference between the two groups. We call this kind of analysis an on-protocol or per-protocol analysis. Now again that kind of analysis gives me a bias away from the null hypothesis, that biases me towards rejecting my null hypothesis. On the other hand, if I analyze them according to the group they started out in, even if they are getting the new treatment, I'm pretending they're getting the original treatment, we call that an intention to treat analysis. It biases my conclusions toward the null hypothesis, we prefer this. 01:59 Why do we prefer this, because science is conservative, we'd like to make it as difficult as possible to reject the null hypothesis, such that when we do reject it, we can be relatively satisfied it was done rationally and because an effect is real. In other words, we always do the intent to treat analysis when we can. It's simply, logically and philosophically preferred. One way to memorize this, is to have the mnemonic; "If you randomize, you analyze", once I've randomized people into their groups, that's where they remain for analysis purposes, even if they move after that. If you randomize, analyze. 02:38 Let's talk about control groups now. A control group is one of the most important foundational ideas in science. If you think about it, anytime I have a treatment group that is undergoing some kind of therapy or treatment, I'm probably always going to measure some kind of effect. 02:53 I don't know if that effect is large or small, unless I'm comparing it to somebody, that's why I need a control group, especially a control group that has circumstances and environments that are very, very similar, if not identical to my treatment group with the exception of the thing that I'm testing, maybe it's a drug. So a control group is the most effective strategy, well one of the most effective strategies, for ruling out the effects of extraneous variables. 03:18 Why? Because I've controlled, hence the name controlled, for all of the factors in both groups, except for that one factor. When I create a control group, I have some options available to me. The control group can receive either none of the treatment, this one's getting a treatment, maybe a drug, maybe something else, I can say my control gets nothing, or I can say it gets the next logical standard treatment, or it gets a placebo, which is a kind of fake treatment. Let's think about the next logical standard treatment for a second, why does that matter? Well if I'm testing a new drug, presumably it's to determine if that drug is better than the one that is currently on the market, not whether that new drug is better than nothing. Pretty much any new drug that I create after millions of dollars of research is going to be better than nothing. It only has value to me if I can show that is better than what else I have. So my control good here should be the other drug that I have, the one that I'm currently using because I'm trying to see if my new drug is better than that. The other reason we'd like to have the other current treatment as a control group is for ethical reasons. So imagine I'm testing a drug that's life-saving or really important for pain management for people who are very seriously ill, if I have a control group made up of very sick people, it's not ethical to give them nothing, I have to give them something. The most ethical thing to give them is the current recommended treatment. 04:48 It makes perfect sense and my study group is getting this new treatment which I hope is better. Placebo is another story entirely and we'll talk about that in a second. Now to draw appropriate valid comparisons between a treatment group and a control group, I have to assume that my groups are relatively equivalent, equivalent in many ways, equivalent in the distribution of variables and equivalent in size. We call the equivalence in size, balance. 05:16 Balance is sometimes hard to achieve, randomization techniques, advance randomization techniques allow us to maximize the chance that we'd have better balance between the groups. When we have control groups though, we have the possibility of biases. Now some common biases in randomized controlled trials are the Hawthorne effect and the Rosenthal effect. We talked about these briefly in the lecture on biases, but I want to go over them again. Hawthorne effect is sometimes called the observer effect. And it's when by the act of simply observing someone, you change your behavior. How this manifests in an RCT? Is that subjects who are in a study modify their behavior because they know they're in a study, they know they are being watched by an investigator. Maybe they want to please their investigator and so they are behaving better. The Rosenthal effect on the other hand is sometimes called the Pygmalion effect and it's kind of the opposite, it's when the investigator causes a change in the subject simply by interacting with them. Sometimes it's called a self-fulfilling prophecy bias, because they're interacting with their subject in such a way that they want to elicit a change subconsciously and they manage to do so. They do so by giving subtle cues either verbally or physically. So imagine we have in RCT that's trying to measure whether or not a new drug reduces the pain of migraine headaches, so we have two groups, we have a treatment group getting this new drug and we have a control group that is not getting the drug, maybe they're getting a placebo, maybe they're getting some other drug. Now subjects may report feeling less pain simply because they're in a study. 07:00 They're spending time with clinicians. They are being looked at. Pain is one of those classic cases of things that are subject to this kind of bias, because it's so amorphous, it's so difficult to measure objectively, it's quite subjective. So maybe they are assuming that they're getting the drug and not the other thing that the control group is getting and so they are feeling, "Ah, I must be getting better", that's an example of Hawthorne effect. 07:23 When they are performing differently and better simply because they think they're being watched and spending time with the clinicians. Rosenthal effect works in a different way, investigators are eager to see their drug work. We spent all this time and energy and money designing an RCT to test this new drug because we expect it to work. So maybe as a result, as the investigator, I'm more enthusiastic about the people who are getting the drug, because "You're feeling better right? You're feeling better. I want you to feel better." Maybe I'm less enthusiastic about those who are not getting the drug because I don't care as much about them, let's say in theory, obviously I do care about them. But they are not getting the drug that I'm trying to test, so I'm spending less time and less enthusiastic about them. 08:07 As a result, maybe the people who are receiving the drug will respond differently, not because of the drug, but because of me spending time with them.

About the Lecture

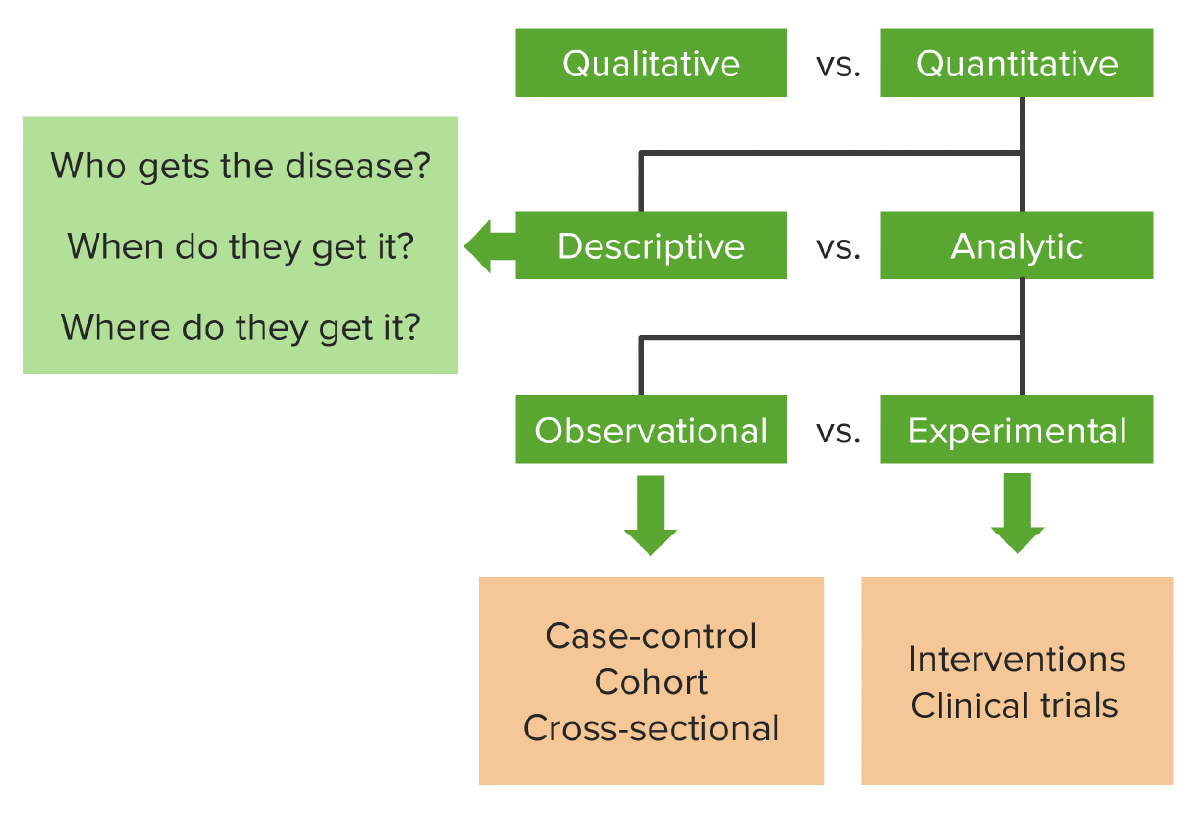

The lecture Groups – Interventional Studies (Study Designs) by Raywat Deonandan, PhD is from the course Types of Studies.

Included Quiz Questions

A certain RCT, studies whether drug X reduces flu symptoms, with 10 subjects in the treatment group and 10 in the control group. In week 2, one subject moves from the control to the treatment group. However, when the results are analyzed, that one subject who moved is analyzed along with his original group, the control group. What kind of analysis is this?

- Intent to treat analysis

- On protocol (or Per protocol) analysis

- Statistical analysis

- Confounder analysis

- Analysis of groups

An RCT is constructed to study the influence of distributing an educational dietary pamphlet on obesity rates among patients at several outpatient clinics. Partway through the study, one of the clinics assigned to the control group inadvertently starts distributing the educational material to their patients, giving their patients the same exposure as the treatment group. Which of the following would you expect if the affected clinic is analyzed with the control group rather than the treatment group?

- Decreased likelihood of rejecting the null hypothesis

- Increased likelihood of rejecting the null hypothesis

- Decreased likelihood of statistical significance

- Increased likelihood of internal validity

- Decreased likelihood of failing to reject the null hypothesis

Why is intention-to-treat analysis generally preferred by scientists over per-protocol analysis?

- It is a more conservative estimate of treatment effectiveness.

- It is more likely to show a treatment effect.

- It minimizes type II error.

- It evaluates noncompliance when analyzing treatment effects.

- It is less likely to be affected by confounders.

Which of the following statements regarding control groups is INCORRECT?

- Control groups are always given the drug of interest in the study.

- Control groups may be used to compare different dosages of the same drug.

- Control groups must be balanced in size with the treatment group.

- Control groups share similar characteristics and demographics to the treatment group.

- Control groups can be used to compare the effectiveness of a drug over no treatment.

Which of the following would be most effective in reducing Rosenthal bias?

- Limit the interaction between the subjects and the investigators

- Avoid letting the subjects know they are being watched

- Use stratified randomization rather than simple randomization

- Increase the number of subjects in the study

- Use a retrospective study design

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |