Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Experiments – Interventional Studies (Study Designs)

-

Slides 08 InterventionalStudies Epidemiology.pdf

-

Reference List Epidemiology and Biostatistics.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

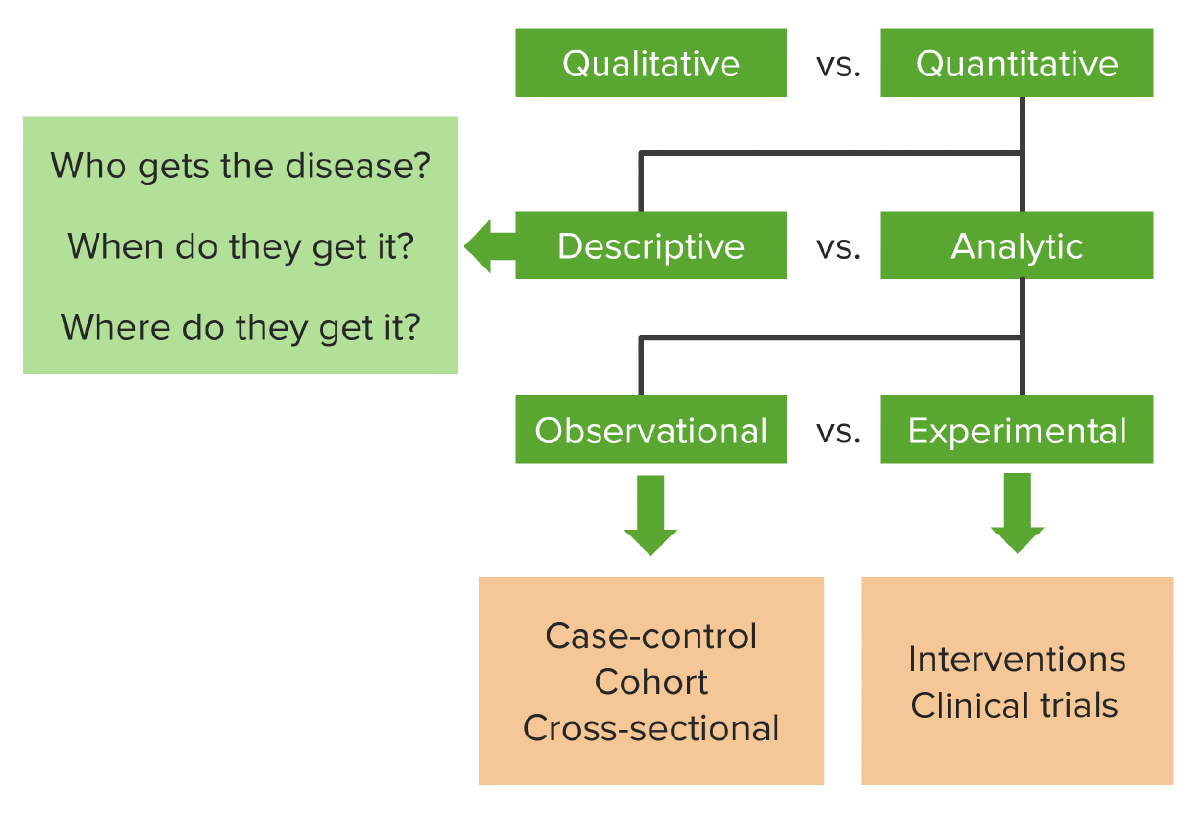

00:01 that I've got that straight in your mind, let's think about the quasi-experiment again. 00:05 The quasi-experiment resembles an RCT, but lacks randomization. Do you remember why we randomized? We randomized to control for extraneous variables, especially the ones we don't know about. So we control for confounding more than anything else. Before we can control for that, quasi-experiments lack internal validity, or at least internal validity is in jeopardy. 00:28 Keep that in mind. Why do we use it then? Well sometimes randomization is not possible, in the example we worked through with the broadcast of the radio documentary on boiling water, you can't randomize that sort of thing. I also cannot control for blinding because people know whether or not they heard a radio broadcast. On the other hand, because it takes place in the real world, it's in a real community where people live and work and they are listening to the radio broadcast and applying it in their real lives automatically. Automatically it has external validity, so we've compromised internal validity, but we've gained a lot of external validity. 01:08 Now let's talk about something called a natural experiment. Something that is quite close to my heart because while I finished my doctorate my very first job interview involved someone asking me about a natural experiment. The job interview was for a position in radiation epidemiology, something that we don't have a lot of data about, especially not about large-scale doses of radiation on the population and my interviewer asked me, "Can you think of a natural experiment from which we can derive data to measure radiation and health?" And I blanked and I couldn't think of one, but the answer is obvious; end of World War II, the dropping of the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that's a classic unfortunate and tragic natural experiment. A natural experiment resembles a randomized controlled trial, but this is when the allocation of the subjects isn't due to randomization, it is due to an external force that the researcher had no control over, like a natural disaster, like a military disaster, or like a proposed law or by-law. So this is how a natural experiment looks. Like the rest of them, we begin with a study population, we allocate our study population to one or two groups, a treatment group or a control group. The allocation though isn't done through randomization like flipping a coin, it is not done through choosing a community like in a quasi-experiment, it's done by an external factor, like a natural disaster. So let's look at an example that's not as depressing as the nuclear bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Let's look at the state of Montana where some towns decided to pass smoking bans and we want to test whether or not passing a smoking ban in your community resulted in let's say, less or poor health. So all we have to do here is find some towns that pass the smoking ban and some towns that didn't. Now you didn't convince them to pass the smoking ban, someone else did. The legislature did. An external force did it. You're now going to reap the data rewards from that choice however. So we find the towns that banned smoking, some towns that did not ban the smoking and we'll see the results from those two towns. 03:19 And again, since the researcher was not the one to determine the allocation, this is technically not a randomized controlled trial. It's probably technically an observational study it can be argued, I would say it's a kind of experiment observational study hybrid. I want to point out that even though I've taxonomized these designs into observational and experimental and so forth, it doesn't really matter which category you think a study goes into, all that matters is, can you interpret the results? The naming doesn't matter; it's the interpretation that matters.

About the Lecture

The lecture Experiments – Interventional Studies (Study Designs) by Raywat Deonandan, PhD is from the course Types of Studies.

Included Quiz Questions

What measure of a quasi-expeirment is affected by lack of blinding and randomization?

- Internal validity

- Generalizability to the real world

- Sensitivity

- External validity

- Accuracy

Which of the following is a requirement for a natural experiment to be conducted?

- An external factor that creates different exposures between groups

- Manipulation of exposures for each group by the investigators

- Data scientists to allow the study to remain blinded to the investigators

- A natural disaster that affects all members of the population

- Legislation that applies universally so all groups are equal

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |