Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Urology Surgery: Urologic Cancers

-

Slides UrologicCancers Surgery.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

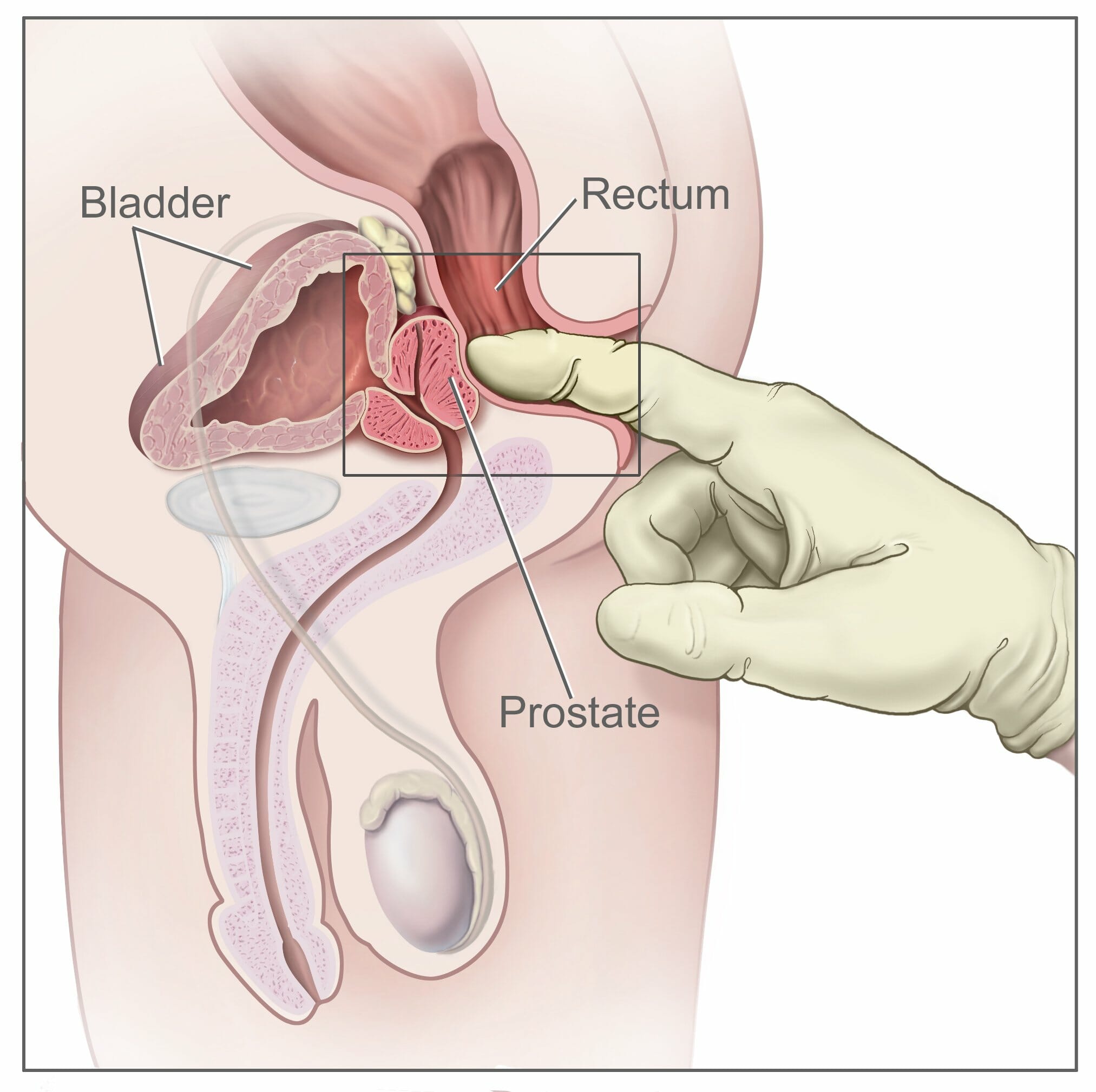

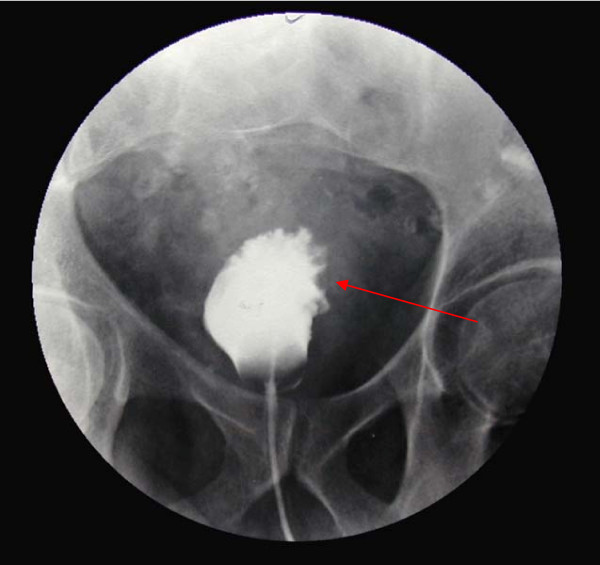

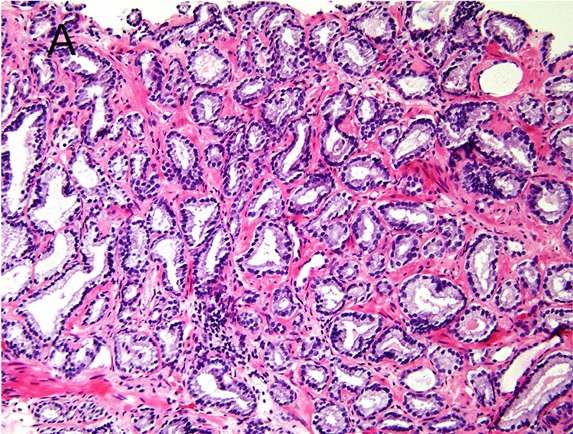

00:01 Thank you for joining me on this discussion of urological cancers in the section of urology. During this module, I’ll mostly focus on prostate and bladder cancer, but please recognize that when we speak about urological cancers, we also include the kidney, as well as the testicles. They’ll be covered under separate modules. Let’s begin our discussion of prostate cancer. Unfortunately, it's one of the most common cancers in men. And with increasing age, the incidence of prostate cancer increases dramatically. However, there's an old saying, with prostate cancer, most elderly men die with prostate cancer as opposed to of prostate cancer. And the reason we say that is because large proportions of men, at the time of death, particularly in elderly men, have some modicum of prostate cancer, and yet they were not the reason why the patient died. Now, quick review of the anatomy. Can you take a look at this image in the center of the screen? The red highlight is the area of the prostate. It also encircles the area of the urethra, called the prostatic urethra. You can imagine, if the prostate is enlarged or there's a tumor in this region that the prostatic urethra could be restricting outflow from the bladder. You can feel for the prostate by inserting a single finger up the rectum as it's shown in this picture. What kind of physical findings should we look for or historical facts? For example, with prostate cancer, the patient may complain of progressive urinary retention, the feeling that there is incomplete voiding. Especially, with bony metastasis, the patient may have back pain, and more frequently, hematuria. Unfortunately, no routine laboratory is indicative of prostate cancer. There’s quite a bit of controversy about screening with a prostatic-specific antigen, also known as PSA level. Despite guidelines suggesting not to routinely get PSAs in patients of average risk, still many doctors do. Now, for physical examination, unfortunately, even though the prostate is easily palpable, it can be inaccurate, particularly if you're trying to differentiate between benign prostatic hyperplasia versus a mass. As depicted in this image, the index finger is inserted into the rectum. And as you hook your finger by 90°, you should feel the prostate. In prostate cancer, you might find nodularity and asymmetry, which is different from benign prostatic hyperplasia, in which the prostate is usually symmetrically enlarged. 02:44 Remember, most patients of prostate cancers have normal digital rectal examination. And although the DRE has long been used to diagnose prostate cancer, no controlled studies have shown reduction in the morbidity or mortality of prostate cancer when detected by DRE at any age. 02:59 So, how do we diagnose? Well, depending on a host of factors including risk factors, family history and your PSA level, the doctor may recommend a transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy. Here, in this ultrasound image, you see the prostate gland. Accuracy of biopsies is usually better under image guidance. Remember, usually multiple cores are taken to maximize sensitivity. There's always the concern of a false-negative study. The Gleason score is a unique scoring system for the description of pathology on prostate biopsies. Based on the Gleason score, the two highest scoring samples are added together for a total score. As you get higher in terms of scoring, the lesion itself is less and less differentiated. For example, Gleason score of one is predominance of the small uniform gland. And it's usually well-differentiated. Next, Gleason 2. It includes more stroma between the glands however still considered well-differentiated. As you progress to level 3 and 4, you also progress in the chain of less and less differentiation. And ultimately, only occasional gland formation and predominant cancer is a late finding and high-grade in terms of Gleason score. As I earlier described, two samples are taken. X plus Y equals the Gleason score. X is the predominant microscopic type and Y is the next most predominant or highest microscopic type. In this series, remember, we take the worst appearing pathology Gleason score. After ascertaining that you, in fact, have prostate cancer, and after determining the patient has no metastasis, it's okay to offer the patient a prostatectomy. And in select patients, particularly those with significant comorbidities, radiation therapy alone may be of an option. Remember, the decision to proceed with surgery is based on life expectancy, chances of lymph node involvement, and the patient condition in general. Recall a scenario where you have a 90-year-old patient who presents for the first time with a diagnosis of prostate cancer. Statistically speaking, that patient is unlikely to outlive the cancer. Therefore, no surgery should be offered to that patient. Now, are there screening guidelines? Of course. In men greater than 50 years of age, a digital rectal examination is recommended. It's unclear what happens if the patient has a family history of prostate cancer. Remember, a large proportion of men in their elderly age group have prostate cancer. So there may actually not be a genetic component. Prostate cancer is slow-growing. That's important. It is said that many men die with cancer as opposed to from it. And typically, with a screening PSA, PSA levels greater than 3 is of a clinical value. This may indicate necessary for the workup. Now, let’s move to bladder cancer. Almost all bladder cancers is derived from urothelium and are consistent, consist of either transitional cell or squamous cell. What are some risk factors? Certain environmental associations with bladder cancer exist. For example, hydrocarbons, smoking. Remember smoking is a high risk factor for many oncologic processes. Arsenic and chronic use or exposure to chemical solvents. Although the exact mechanism is unknown, these associations seem to be highly correlated. What are some physical findings of bladder cancer? Again, one of the earliest findings is probably hematuria and non-specific bladder irritation and suprapubic discomfort. Depending on the location of the bladder cancer, patients may also experience incomplete voiding. These symptoms may be difficult to differentiate from prostate cancer. Once again, laboratory values are of little use to indicate that there is bladder cancer. However, urine cytology may be helpful. Urine cytology allows a pathologist to evaluate whether or not malignant cells are contained within the urine. Generally speaking, for the diagnosis of bladder cancer, cystoscopy is recommended. Cystoscopy entails insertion of a small catheter that has a camera on it through the penis, through the urethra, into the bladder. Via under direct visualization, cystoscopy is able to visualize as well as guide biopsies. These are direct biopsies under direct visualization. Now, let's say that you've done the complete workup and you’ve decided to offer surgery to the patient, the decision about surgery and what appropriate surgery is necessary depends on whether or not the cancer has invaded the muscle. With muscle invasion, a radical cystectomy with lymph node dissection in the pelvis is necessary. This generally involves reconstructing or having appropriate drainage of the ureters. Let's say that the pathology shows no muscle invasion. In this situation, the patient may be candidate for a transurethral resection of the bladder tumor, also known as a TURBT. Clearly, this is a less invasive procedure. Now, it's time to remind you of some important clinical pearls and high-yield information. Remember, bladder cancer is suspected when there is positive cytology and based on cystoscopy. 08:52 And spontaneous hematuria should alert the clinician to possibility of bladder or prostate cancer. 08:58 If on examination you are presented with a scenario of an elderly gentlemen with intermittend hematuria please consider these in your differential diagnosis. Thank you very much for joining me on this dicussion of urological cancers.

About the Lecture

The lecture Urology Surgery: Urologic Cancers by Kevin Pei, MD is from the course Special Surgery. It contains the following chapters:

- Urology Surgery – Urologic Cancers

- Bladder Cancer

Included Quiz Questions

Which of the following are the MOST common symptoms of prostate cancer?

- Urinary retention, back pain, and hematuria

- Cloudy urine, back pain, and hematuria

- Urinary incontinence, back pain, and burning on micturition

- Intense urge to urinate, back pain, and cloudy urine

At what age should screening for prostate cancer begin?

- > 50 years

- > 40 years

- > 55 years

- > 45 years

- > 60 years

What is the Gleason score of a tumor that is graded 2 and 3 on pathology?

- 5

- 2

- 1

- 4

- 6

What is the highest possible Gleason score?

- 10

- 8

- 9

- 6

- 5

Which type of cell is MOST commonly involved in bladder cancer?

- Transitional cells

- Peripolar cell

- Epsilon cells

- Leydig cell

- Chromaffin cells

Customer reviews

3,5 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

1 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

1 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

It was puntual and have the more significant information about the topic.

I don't feel it went into enough detail about the different types of bladder cancer