Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Workup of Proteinuria and Nephrotic Syndrome in Children

-

Slides Proteinuria and Nephrotic Syndrome Pediatrics.pdf

-

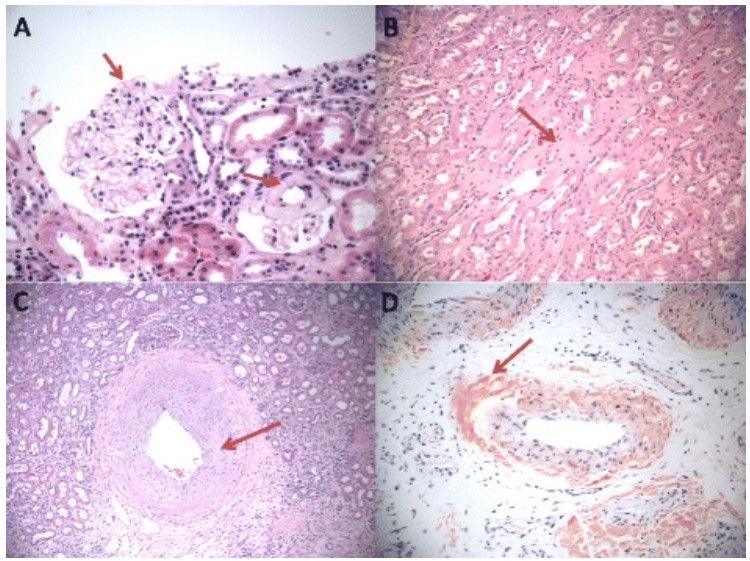

Download Lecture Overview

00:01 So if we see a child who has proteinuria, what are we going to do? Let’s say this girl comes in and she has trace protein. 00:11 Well, we’ll probably do the first void urine dipstick. 00:16 So we send the child home with a cup, have them pee in the cup first thing in the morning and bring it in and then if there is no protein in that urine, we’re done. 00:26 But if it is positive, we’re going to work the child up. 00:29 However, if the child has +1 or more protein or if we decide to work the child up, we’re going to obtain her first morning void and then we’re going to check urinalysis and we’re going to do the check of the urine protein to creatinine ratio. 00:44 So let’s imagine we have a child with a protein to creatinine ratio. 00:50 If it’s more than 0.2, let’s do a complete H&P. 00:55 Let’s check the urinalysis. 00:57 We’ll get C3 and C4 levels to try and drill down on what is causing the problem. 01:03 We may get other testing as needed. 01:05 If we suspect lupus, we would check an ANA. 01:07 If we have reason to suspect HIV, we would do that test. 01:11 If we suspected post-strep glomerulonephritis because there was also blood and the child had a history of sore throat, we might get ASO titers. 01:19 Likewise, we might get renal ultrasounds or VCUG if we’re worried about reflux. 01:25 And we might do a renal biopsy if we can’t figure out what’s going on. 01:30 If it’s less than 0.2, we’re not going to do anything right now. 01:34 Let’s check it again next year or if the patient comes in symptomatic, say with generalized edema. 01:42 But what if our little girl is symptomatic? What if she has what we suspect as nephrotic syndrome? She has protein in her urine and she has edema. 01:54 Well, here’s an electron micrograph of a child with nephrotic syndrome and what you can see is the podocytes. 02:03 The areas around that glomerular filtration area are widened. 02:07 They’re damaged and as a result, fluid is able to get through and protein is able to get through. 02:14 It’s no longer an effective filter. 02:16 So these children will have proteinuria. 02:18 They may have hypoalbuminemia from their loss of albumin into the urine. 02:25 They will develop edema and interestingly, they can also get a hyperlipidemia. 02:31 The reason for the hyperlipidemia is complex and we don’t need to go into it. 02:36 But what’s key is that we’re measuring for hyperlipidemia, high LDL for example, because we want to make the diagnosis. 02:45 In children, a high LDL is not particularly concerning for cardiovascular events. 02:52 We are not worried they’re going to have a heart attack as a child. 02:54 We are using the hyperlipidemia value primarily as a diagnostic measure. 03:02 Patients can be quite edematous with nephrotic syndrome. 03:06 The most likely place is in this first child where you have swelling around the eyes. 03:11 It can be gravitationally dependent and so, you should look around the genitalia as well or it could be diffuse as in our child with his whole face is really swollen. 03:22 So when we look at nephrotic syndrome, we think about causes as either primary or secondary. 03:29 Around 90% of cases of nephrotic syndrome in children are primary. 03:34 It can be idiopathic or it just happens. 03:37 It may be FSGS. 03:39 We showed examples of one FSGS earlier on this talk. 03:43 It could be minimal change disease. 03:46 We’ll talk about that in a minute. 03:48 Or it could be mesangial proliferation. 03:51 There are several diseases that can cause nephrotic syndrome level urine proteinuria. 03:58 Examples include lupus, NSAID administration or other drugs, post-strep glomerulonephritis which is more common the blood but can also be protein, Henoch-Schonlein purpura which is more commonly blood but can also be protein or simply just renal scarring. 04:18 There are also some gene mutations which can predispose patients to nephrotic syndrome. 04:24 The NPHS2 mutation encodes for podocin. 04:29 This is the protein in the podocytes of the glomerulus and confers a bad outcome in nephrotic syndrome. 04:36 These patients frequently progress to end-stage renal disease. 04:41 The WT-1 mutation is in the Wilms tumor suppressor gene. 04:46 It’s associated with certain types of nephrotic syndrome and especially the Denys-Drash syndrome. 04:55 NPHS1 mutation is a Finnish-type congenital nephrotic syndrome which presents within the three months of life. 05:03 It’s unlikely, I would guess, that an exam would ask you about certain specific mutations but you should keep in mind that there are genetic influences that can worsen nephrotic syndrome. 05:16 So if we suspect nephrotic syndrome, we are going to do some testing specifically the urinalysis, the protein to creatinine ratio which as we said is more than 2. 05:25 We will check serum albumin especially in edematous child, they are usually quite low. 05:30 And like I said before, we’re going to check for hyperlipidemia especially at high total cholesterol. 05:37 Electrolytes maybe abnormal especially patients may develop a low sodium as they’re holding on to fluid. 05:44 Patients may have an elevated BUN/creatinine if they have renal insufficiency. 05:49 And in patients who have lupus, an ANA is valuable, but remember ANA false positive rates are very high, about a third of people have a falsely positive ANA. 06:02 Rarely, hepatitis can cause a nephrotic syndrome. 06:05 So in patients where we have hepatitis, we would screen for hepatitis B or C. 06:11 C3 and C4 are abnormal in lupus and C3 is abnormal in post-strep glomerulonephritis. 06:20 So let’s switch gears and talk a little bit about the minimal change disease. 06:26 I’m mentioning this because the name itself is often confusing to people. 06:31 Minimal change disease is called minimal change disease because the biopsy looks normal when you look at it in the microscope. 06:40 You have to do electron microscopy to see what the problem is. 06:45 An electron microscopy takes a while before you get your results back. 06:50 This is not a benign disease. 06:52 Minimal change disease does not mean that the changes are minimally causing problems. 06:57 It means that you can’t see the changes under the microscope. 07:02 So these patients may not do well, most do do well, but many do not. 07:10 So how do we manage nephrotic syndrome? We’ve talked about all these different diseases. 07:16 We need to drill down on what we typically do. 07:20 90% of patients will respond well to steroids. 07:25 Most of these have minimal change disease. 07:28 It’s a common cause of nephrotic syndrome. 07:31 So when you see a patient with nephrotic syndrome, you’re going to start steroids. 07:36 If the patient does not respond well to steroids, that’s when you need a biopsy. 07:41 We don’t biopsy them immediately because the fact to the matter is many will respond to steroids and that’s our treatment. 07:48 So knowing exactly which kind for sure may not be necessary and the renal biopsy is not a totally benign phenomenon. 07:58 We do use ACE inhibitors or if they’re not tolerating that, an Angiotensin II receptor inhibitor for patients with hypertension associated with their nephrotic syndrome. 08:10 So how do we manage these steroids? We’re going to start them off on prednisone and we’re going to leave them on prednisone for a long time, six weeks. 08:20 Then, we will do a gradual taper off the prednisone for six weeks. 08:26 Not only is this preventing a rebound steroid deficient state, but also it’s allowing for a gradual taper of the effect against the kidney. 08:37 And then, we’re simply going to watch them for a relapse. 08:39 These children will need to be screened routinely for protein in their urine. 08:45 Around 5% of children with minimal change disease develop end-stage renal disease or die from their illness. 08:53 The majority get better. 08:56 Long term complications from steroids are difficult to manage and this can be an ongoing problem in these patients. 09:03 In patients with poorly responsive nephrotic syndrome, they may end up with the sequelae of chronic steroid use like moon facies or striae or decreased bone mineral density. 09:16 Overall for patients with nephrotic syndrome, the prognosis is divided into thirds. 09:23 One-third of patients will never relapse again, are going to live long happy lives without any kidney problems. 09:31 One-third of patients will suffer a few relapses here and there, will end up on recurrent steroids but will generally be able to control things. 09:41 But one-third of patients end up with frequent relapses, end up on steroids for long periods of time and will suffer the consequences of that care. 09:51 That’s my summary of nephrotic syndrome and proteinuria in children. 09:55 Thanks for your attention.

About the Lecture

The lecture Workup of Proteinuria and Nephrotic Syndrome in Children by Brian Alverson, MD is from the course Pediatric Nephrology and Urology.

Included Quiz Questions

Which of the following statements is TRUE about minimal change disease?

- Light microscopy shows normal findings.

- It rarely responds to steroids.

- It is diagnosed by immunohistochemistry.

- It occurs exclusively in boys.

- Most patients are older than 20 years.

A normal result of which of the following laboratory tests makes the diagnosis of SLE least likely?

- Antinuclear antibody

- Urine analysis

- Serum albumin

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- C3 and C4

A 5-year-old child presents to the physician with headache and mild facial puffiness. He had a sore throat 2 weeks ago. His BP is 120/90 mm Hg. Urinary evaluation shows RBC casts and 2 grams of protein/24h. Which of the following is the most appropriate next step in diagnosis?

- C3 and C4 titers

- ESR

- Antinuclear antibody test

- Voiding cystourethrogram

- Renal Biopsy

Which of the following is seen more commonly in acute glomerulonephritis than in nephrotic syndrome?

- Hypertension

- Proteinuria

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Edema

- Hyperlipidemia

A neonate develops edema of the face and lower limbs in the first week of life. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

- Finnish-type congenital nephrotic syndrome

- Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis

- Minimal change disease

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

2 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

Crystal clear and focused on the most important aspect for a pediatrics resident. I also liked that Dr. Alverson expanded on the secondary effects of steroids.

Dr. Brian Alverson is very clear in his explanations, I totally recommend his lectures.