Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Hepatitis B Virus – Hepadnaviruses

-

02-35 Hepadnaviridae.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

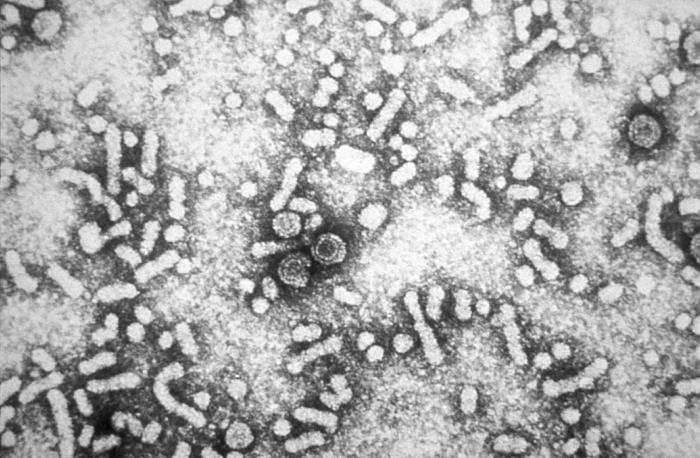

00:00 The Hepadnaviridae viruses. The hepatitis B viruses are small and enveloped with a circular, partially double-stranded DNA genome, and importantly, they encode their own reverse transcriptase. The viruses themselves are resistant to low pH which is important as they are aspirated and enter the circulation via the stomach. They also are resistant to moderate heating as well as detergents in terms of cleaning in the hospital or healthcare setting. And, typically, as we'll see, the hepatitis B virus can cause both an acute and/or a chronic infection. It's quite versatile in its cause of disease. Transmission, as you are probably aware, is anything and everything especially exposure to blood and body fluids. So, a parenteral exposure, sexual exposure, babies born to mothers actively infected or to even chronically infected, of course, are at risk. The incubation then of hepatitis B virus is months and sometimes even longer than that. So, let's walk our way through the replication of hepatitis B virus. Again, it's a little bit different because it carries its own reverse transcriptase. We'll start with the complete virus as it attaches to and embeds itself to its target hepatocyte. It then sheds its external envelope injecting the capsid into the cytoplasm and ultimately injects the core, the DNA material, into the nucleus of the hepatocyte. There, the viral genome is first transcribed into long, double-stranded RNA and then back transcribed to DNA circles which, again remember, are not completely double-stranded. These then exit the nucleus and are packaged into new capsid material which then gains further envelope material on its way out and eventually lyses and extrudes itself from the hepatocyte. So, it's, again, as we're seeing as a recurrent human viruses when the fully-formed virus leaves the cell, in this case the hepatocyte, is when lyses occurs and the effect itself creates an inflammatory reaction. When you see the anti-HBc AG, IgG together with anti-HBs, an antibody to the HBV surface antigen when you were dealing with some of those previously been infected. If we see anti-HBs alone without an antibody to HBc, then the immunity is likely secondary to vaccination. In both of these cases, the patient will typically have lifelong immunity. Now, if we see persistence of the HBs surface antigen, HBV DNA with or without HBe antigen or we see HBs antigens persisting for more than 6 months, we know we're dealing with a chronic infection. It is possible for these patients to have anti-HBs antibodies, but if you still have persistent HBs antigen, it means they are not effectively neutralizing the virus. These images are schematic representations of serological responses during an acute and chronic HBV infection in relation to the serum ALT concentrations. The left panel shows an acute infection. It is characterized initially by the presence of HBe antigen, HBs antigen and HBV DNA beginning in the pre-clinical phase. IgM anti-HBc appears early in the clinical phase. This is an important point as the combination of this antibody and HBs antigen make the clinical diagnoses of an acute infection. Recoveries are accompanied by normalization of the serum ALT levels, disappearance of HBV DNA, the seroconversion of HBe antigen to anti-HBe. 03:53 Subsequently, HBs antigen to HBs seroconversion and a switch from IgM to IgG anti-HBc. 04:02 Thus, a previous HBV infection is characterized by anti-HBs and IgG anti-HBc. The right panel shows that a chronic infection is characterized by persistence of HBs antigen, HBV DNA and HBe antigen for a variable period in circulation. Anti-HBs is not usually seen but in approximately 20% of patients, a non-neutralizing form of anti-HBs can be detected. 04:28 Persistence of the HBs antigen for more than 6 months after an acute infection is considered indicative of a chronic infection. To again refresh our memory of where these different components are that we test for, we’ll look first at the core antigen. It's a major core antigen. And as you can see, it lies underneath the envelope shown in purple on this image and instead is the red ring-like structure. That represents a surrounding group of core antigen to protect the internal capsid, and this contains both genome and core enzymes. The surface antigen, as the name would suggest, it's not too hard, lives on the surface, and that would be present in that purple surrounding envelope material which you see present on the image. And then the E antigen, now this is closely approximated in the space around the core antigen, and so when one sees expression of the E antigen, that means that initial uncloaking or removal of the envelope has occurred, and this typically is detected in the bloodstream. So, pathogenesis, hepatitis B virus enters; it’s typically either injected through parenteral or through some other exposure to blood and body contents, it survives any acid challenge, and creates a viremia, travels to the blood stream to the liver. If the patient has been previously immunized against hepatitis B surface antigen, then no further action can occur. There's no ability for the virus to attach and, in fact, the immune system can detect this new virus and get rid of it. However, assuming the patient is unimmunized then we have attachment of the hepatitis B virus as we talked about before to the hepatocyte and it replicates, causing low-level inflammation but no liver damage. During this incubation period, however, we can have a very strong cell-mediated immune response from the human’s immune system. And if there is a strong response, meaning it’s attacking those inflamed or lytic hepatocytes that acute disease, acute hepatitis will develop, occurring in about a quarter of patients who are infected with hepatitis B, and this is highly likely to cause complete resolution and development of a strong and protective immune response. The patient will survive that quite well. If, as is more common, the patient has a mild immune initial response, this is unfortunate because it means that they are highly likely to have a chronic infection, and if so, that means that they can develop further disease, further cirrhotic disease going on. Looking even more specifically at what happens with the infected hepatocyte, the hepatitis B surface antigen is a very active or very highly able antigen to trigger an immune response and it frequently creates a type 3 hypersensitivity reaction which can cause or contribute to that active hepatitis. If, however, in the setting of chronic infection, there is a reactivation and/or there is a co-infection with hepatitis D or delta, then the patient is at high risk to develop permanent liver damage accompanying with cirrhosis which occurs in 10%. The patients then who have over 30 years of that chronic low-level infection, the ones who had a mild immunologic response to the initial acute infection are at high risk to develop ultimately a hepatocellular carcinoma. So, in this case, although it may be unpleasant, it's far better to have the acute fulminant hepatitis, get it over with, and get a sero-protective response than to be cursed with a mild initial reaction, mild or no hepatitis, but then a chronic infection.Vaccinations also exist, and vaccinations include a non-functioning hepatitis B surface antigen subunit. This vaccine is administered to all newborns typically in the first 2 weeks of life and, again, at two other points in a primary care series depending on what country one lives in. Healthcare workers, if not previously vaccinated as newborns themselves, also deserve immunization. And then, of course, those patients who are at risks. So, transplant coming up, patients require multiple transfusions. The treatment of chronic HBV infections depends on several factors including ALT levels which are an indirect measure of liver inflammation, the presence of cirrhosis, the patient’s immunological response to the infection, for example, their HBeAg levels, the HBV viral load and genotype as well as the patient demographics including things such as age over 40, a family history of cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma. The goals of therapy are to suppress HBV DNA levels, seroconvert HBeAg positive to anti-HBeAg positive and to lose HBsAg positivity. For patients without cirrhosis who are treatment naive and not pregnant, the first line therapy is pegylated interferon and reverse transcriptase inhibitor such as tenofovir or entecavir. The efficacy of this treatment is not perfect, with only 5% losing their HBsAg positivity and 40% who are HBeAg positive, seroconverting to anti-HBeAg but only after 5 years of treatment.Typically, lifelong reverse transcriptase inhibitors are recommended but the interferon side effects limit its use to only a 48-week course. 10:48 For patients with cirrhosis, we also treat with reverse transcriptase inhibitors though all of these patients will require a lifelong treatment. You must also screen for hepatocellular carcinoma every 6 months as chronic HBV is the leading cause of hepatocellular carcinoma in the world. Patients are typically monitored with biomarkers of disease activity such as HBV DNA, ALT levels, HBeAg, anti-HBeAg and HBsAg levels. 11:18 Creatinine and phosphate supplementation can help patients with RTI side effects. 11:24 Additionally, all patients with chronic HBV should avoid alcohol, get the hepatitis A vaccination and reduce transmission to others through practices including safe sex, encouraging partner HBV vaccination, not sharing their toothbrushes or razors and not donating blood products, organs, or sperm. So, hepatitis B virus is absolutely something which occupies the attention of those of us in hospital-acquired infection prevention careers but also for those who work with high-risk patients who are at risk for acquiring the virus through sexual practices, transfusion, parenteral, etc. It's a complicated virus but it's quite instructive in understanding how a viral growth pattern can inform its testing strategy.

About the Lecture

The lecture Hepatitis B Virus – Hepadnaviruses by Sean Elliott, MD is from the course Viruses.

Included Quiz Questions

The genome of the viruses responsible for hepatitis B is best described as...?

- ...circular, partially double-stranded DNA.

- ...circular, partially double-stranded RNA.

- ...linear, partially double-stranded DNA.

- ...linear, partially double-stranded RNA.

- ...linear, partially single-stranded RNA.

Which of the following enzymes is produced by the hepatitis B virus that plays a vital role in its replication and pathogenesis?

- Reverse transcriptase

- RNA polymerase

- DNA hydroxylase

- RNA hydroxylase

- RNA reductase

In an individual vaccinated against hepatitis B virus, which of the following serological markers do you expect to find?

- HBsAg antibody

- HBeAg antibody

- HBcAg IgM antibody

- HBcAg IgG antibody

- HBV DNA

Which of the following types of hypersensitivity reactions is triggered in response to hepatitis B surface antigen?

- Type III

- Type I

- Type II

- Type IV

- Type V

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |