Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Development of Small Airways and Lungs

-

Slides 06-37 Development of the small airways and lungs.pdf

-

Reference List Embryology.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

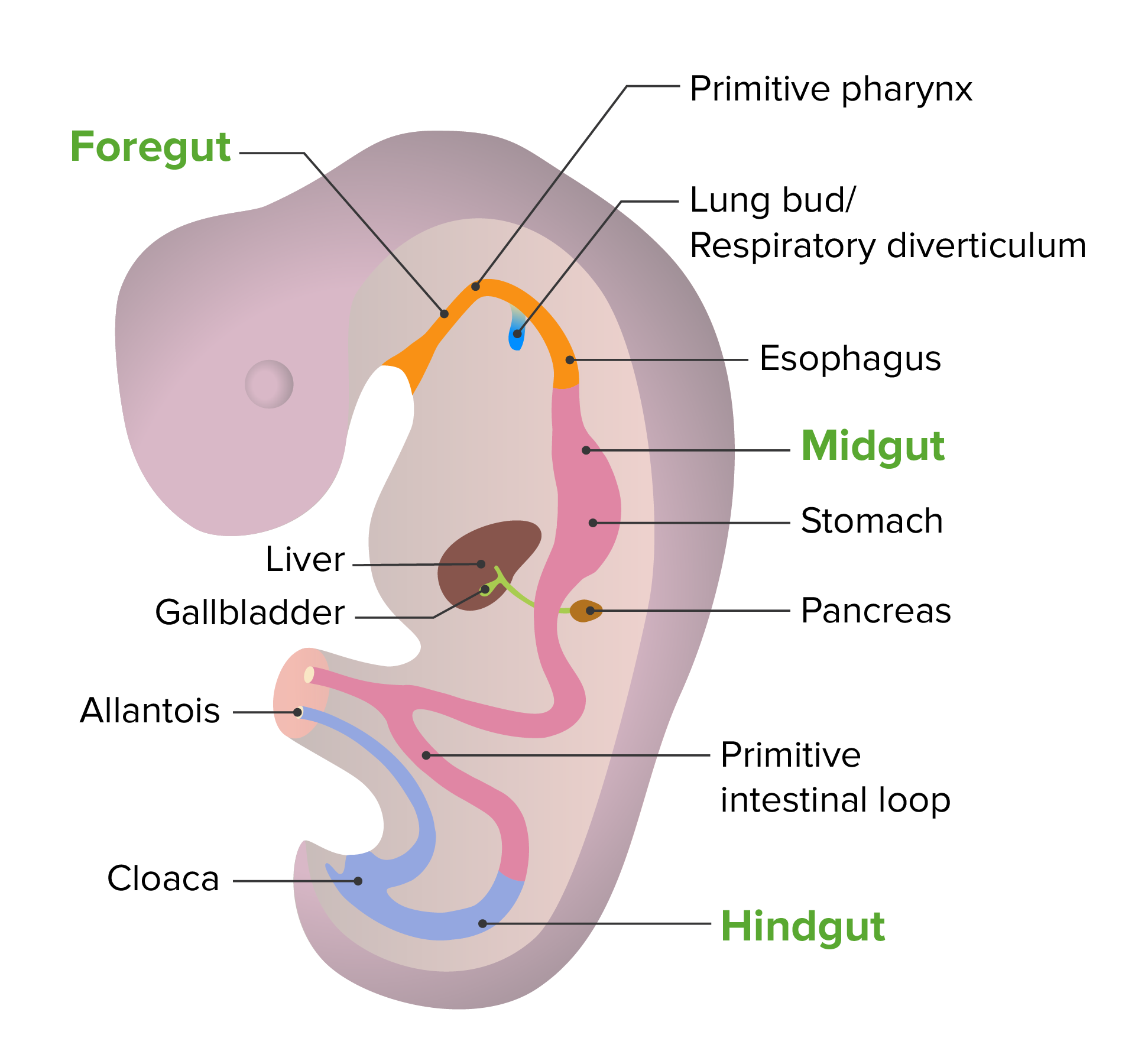

00:01 We will finish our look at respiratory system development by seeing how the smallest airways and actual gas exchange surfaces develop. 00:08 Now, you may recall that we have approximately 23 generations of branching from the respiratory diverticulum of the foregut to the tinier and tinier airways that invade surrounding mesoderm that's going to become the lungs. 00:23 Now, as these cells move into the surrounding mesoderm, they're going to adhere to nearby blood vessels. 00:30 So the airway is going to get closer and closer to the vessels until they actually very closely associate and start to spread out and thin against one another. 00:40 The terminal sacs of this airway are going to become the alveoli. 00:45 The actual gas exchange structures of the mature lung. 00:48 Early on in this process, we're gonna pass through three stages. 00:52 The first stage is called the pseudoglandular phase and runs from weeks 5 to 16. 00:59 If we look at the picture here, histologically, these developing lungs look a lot like a gland. 01:04 A lot of tissue with a lot a little tiny spaces within it, similar to how a gland has lots of little ducts running through it. 01:12 But these are actually the primordia or the early bronchioles invading the lung tissue. 01:18 We move then to the canalicular phase which runs from about week 16 to 26. 01:24 The airways have started to enlarge and the nearby connective tissue has become thinner and thinner in appearance and we're gonna get closer and closer association of the airway with the vessels that are in the area. 01:37 And then, we finally enter what's called the terminal sac stage from weeks 26 until birth. 01:44 In this stage, the airways have gotten larger and larger, but the smallest areas of them, the terminal sacs, have gotten very close to the airway blood supply. 01:55 And so, we have the airway and blood supply meeting, becoming thinner, and at this point, it is actually possible for gas exchange to occur. 02:03 Because of this, 26 weeks is the lower limit for how premature, premature babies can be and still survive. 02:12 Now, let's take a look at how the cells of the airway interact with the cells of the capillary. 02:17 Capillaries are lined by what's called an endothelial epithelium. 02:22 Very thin squamous cells. 02:24 The alveoli however are initially very thick and we need those cells to get thinner so that we can have gas move to and from the blood and airway with minimal resistance. 02:35 And that's gonna occur when the lining of the airway differentiates into flat type I pneumocytes and relatively cuboidal type II pneumocytes. 02:44 Because the type II pneumocytes are relatively large, we don't want them taking up much space but they are vitally important partially, because they are the stem cell for further type I and type II pneumocytes, but also, because they will be secreting surfactant. 02:59 Now, surfactant allows the lungs to inflate but right now, let's return to how the type I pneumocytes get flatter and flatter and are getting closer and closer to the capillaries. 03:11 The flatness of these cells allows gas exchange to occur and what's really interesting is that these pneumocytes are only about 16% present at the time of birth. 03:21 Our respiratory system keeps getting more and more fine-tuned, finer detailed, and the capillaries and type I pneumocytes get closer and closer until we're approximately 10 years old. 03:33 So we have our respiratory system developing well after the point of birth. 03:37 But by the end of month six, the type II pneumocytes are not only present, but they're secreting that surfactant and it's kind of an oily secretion that spreads out across the entire airway. 03:49 And it decreases the surface tension so that when the lungs expand, they expand uniformly and they don't collapse in one place and expand elsewhere to a hyperactive degree. 04:01 The most common cause of respiratory failure in newborns is called RDS, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. 04:09 And this occurs when there's too little surfactant present in the airways to allow smooth expansion. 04:14 Essentially, if we have too little surfactant, some areas will inflate and just keep inflating, becoming hyperinflated. 04:21 Whereas, others will undergo collapse which is called atelectasis. 04:25 So if we have surfactant present, we're gonna be able to expand clearly. 04:29 But without it, we're gonna have some places expand too much and some too little. 04:34 Now, it's associated with the premature birth but it can also occur with gestational diabetes. 04:40 So you wanna make sure that you're aware of that when working with patients and getting them prepped for delivery. 04:45 Women in premature labor may actually be given glucocorticoids which jump starts the production of surfactant in the embryo. 04:52 Premature infants can also be given artificial surfactant into their airways to help where their own type II pneumocytes aren't quite capable yet. 05:01 So this artificial surfactant can allow expansion so then, we only have to worry about getting them enough oxygen rather than worrying about that and the fact that their lungs are inflating improperly. 05:12 One way that you can diagnose possible RDS is through the ratio of lecithin to sphingomyelin and these are two components of the surfactant that can be measured in the amniotic fluid. 05:23 You might recall that we had amniotic fluid surrounding us during development and as we're developing, we breathe it in and breathe it out, and in the process, some of the things released by our airways wind up in measurable quantities in the amnion. 05:40 So looking at the ratio of lecithin to sphingomyelin, if you have a ratio of about 2.4 or more, that means that the fetus is most likely capable of surviving and breathing on its own. 05:51 A ratio below 1.5 points to very, very likely RDS and you wanna be ready for it if premature delivery is on the way. 06:01 Thank you very much and I'll see you for our next talk.

About the Lecture

The lecture Development of Small Airways and Lungs by Peter Ward, PhD is from the course Development of Thoracic Region and Vasculature.

Included Quiz Questions

What is the most common cause of respiratory failure in newborns?

- Respiratory distress syndrome

- Aspiration

- Sepsis

- Congenital heart disease

- Tracheomalacia

What can be given to women in preterm labor in order to induce fetal surfactant production?

- Glucocorticoids

- Mineralocorticoids

- NSAIDs

- Sex hormones

- Immunomodulators

What is the lowest value of the lecithin/sphingomyelin ratio that will indicate fetal lung maturity and a low risk of having respiratory distress syndrome?

- 2.4

- 2.9

- 1.5

- 1.8

- 1.6

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

2 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

very good reading, helped me a lot, thank you very much

Professor Ward is excellent! He ties this well with histo as well!