Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Cirrhosis: Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

-

Slides GIP Cirrhosis.pdf

-

Reference List Pathology.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

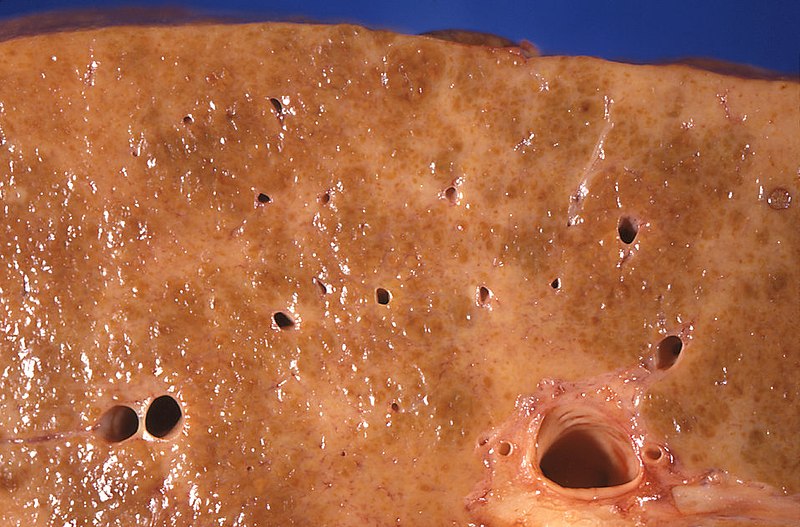

00:01 Welcome. 00:02 With this talk we're going to discuss a really important entity, cirrhosis. 00:07 So as indicated right here on the slide, cirrhosis is end stage liver damage with architectural and functional distortion. 00:14 That is due to liver scarring or fibrosis. 00:17 I will say the liver has a remarkable regenerative capacity, you can cut out 90% of the liver if there's no underlying disease, all of that liver will regenerate. 00:29 However, the regenerative capacity of the liver is not infinite. 00:33 And you can exceed that with recurrent injury, as we'll talk about shortly. 00:38 The epidemiology of cirrhosis. 00:41 There are a whole bunch of different causes, as we'll see in the next section of this talk. 00:46 But a significant number of people in a population, 30 per 100,000, almost 5 million people in the United States for example, are affected with cirrhosis, which is end stage disease, you cannot recover from cirrhosis, all you can do is treat what you have. 01:03 Men, probably because of behavioral things that they do like drinking are more commonly affected than women. 01:11 It is the eighth leading cause of death in the United States, so approximately 50,000 deaths per year are due to cirrhosis. 01:18 So this is not a trivial disease, it's not an uncommon disease, it is not a non lethal disease, this is a bad disease. 01:26 The three most common causes are chronic infectious hepatitis, so that's going to be hepatitis B and hepatitis C. 01:34 As we increasingly vaccinate the world's population, the incidence of hepatitis B associated cirrhosis is going down. 01:42 Hepatitis C in the industrialized nations of the world is also going down because we have very good therapy for hepatitis C. 01:51 But in developing parts of the world, Hepatitis C is still a major cause. 01:56 Alcoholic liver disease, another very common cause, and then increasingly with the obesification, increasing obesity of our population, non alcoholic fatty liver disease associated with obesity is becoming probably the leading cause is certainly in the industrialized parts of the world for cirrhosis. 02:20 Elevated iron, chronic elevated iron, autoimmune hepatitis, primary autoimmune disease involving the biliary tree, Wilson's disease, which is a copper metabolic defect, insufficiency, or abnormal mutations in Alpha-1 antitrypsin, etc. 02:41 These are all other causes and there the list goes on and on and on. 02:44 But remember the top three: hepatitis, alcohol and fatty liver disease. 02:49 The pathophysiology of cirrhosis. 02:51 What is being shown here is the normal architecture lining the sinusoids of our liver. 02:59 The hepatocytes are lined up in a nice cords, and then they are facing onto a sinusoid which contains the blood supply. 03:09 There is a space in between called the space of disse, and in there live stellate cells. 03:15 The stellate cells are going to be the precursors to the hepatocytes, they're going to be also important for regulating blood flow. 03:22 They're going to be important for antigen presentation and a whole variety of things. 03:26 The stellate cells are usually a minor player in the normal hepatic organization when there isn't much damage. 03:34 And also in the space of disse but also in the sinusoids are Kupffer cells. 03:40 These are the liver version of macrophages. 03:44 So in addition to the endothelial cells lining the sinusoids, those are going to be our four major players within the hepatic parenchyma. 03:53 When we injure the hepatocytes, a number of things happen. 03:57 So we have a variety of inflammatory mediators that are elicited. 04:02 Macrophages, the Kupffer cells become activated and release inflammatory mediators such as IL-1, IL-12, IL-18. 04:11 They will drive in concert, the activation of the stellate cells because we've damaged hepatocytes, we need to regenerate hepatocytes and we need to rev up the stellate cells to do that. 04:26 While the stellate cells are also not just going to help us regenerate hepatocytes and be the precursors but they're also going to initiate increased extracellular matrix deposition, that's part of the body's way of dealing with injury is we lay down some scar. 04:42 And with recurrent bouts of injury to hepatocytes, you can have so much stellate cell activation and so much fibrosis that you end up with cirrhosis, and we'll see how that impacts then liver function and flow of blood through the liver. 05:00 Here's our normal appearing liver overall, we have the blood vessels, the sinusoids, lined by the hepatocytes and then keeping in mind the architecture were in the space of disse sub stellate cells and macrophages. 05:14 With cirrhosis liver becomes smaller and becomes irregularly scarred. 05:20 So you will have zones of relatively normal hepatocytes within a ball within a sphere, trying to regenerate trying to make the whole new liver but they will be encased by bridging fibrosis, scar that runs from portal triad to portal triad and from central vein to portal triad and from central vein to central vein. 05:41 In that way, we have a diffusely, scarred, withered liver, that is the cirrhotic liver. 05:49 So early on, because liver has such remarkable regenerative capacity and we're over engineered we have much more liver than we need. 05:58 Small amounts of cirrhosis, small amounts of scarring will initially be able to be compensated for by the excess liver capacity and patients will be asymptomatic. 06:08 However, with time with increasing amounts of scarring, then the hepatic function is going to be compromised. 06:15 And the compromise leading to the compensation is predictable based on what the liver does. 06:20 So for example, the liver is responsible for metabolizing blood that comes out of the GI tract metabolizing the contents of the blood coming out of the GI tract. 06:29 So there is a portal blood flow from the small and large bowel that goes through the liver. 06:35 With progressive cirrhosis, that blood flow is severely compromised, it can't flow through all that scar. 06:43 And as a result, you will have a mechanical increase in pressure and that will lead to ascites, so accumulation of fluid within the peritoneal cavity. 06:54 Also there are portosystemic anastomoses, so of the portal circulation is also through venous anastomosis connected with the systemic venous return. 07:07 As we obstruct the portal flow, that blood is shunted into the systemic venous system and will get varices, will get dilated veins in a variety of locations, some of which may lead to significant pathology. 07:21 And we'll cover that in a subsequent slide. 07:23 The spleen also drains through the portal system. 07:26 And if the splenic circulation is compromised, then you get this big dilated boggy spleen, so called hypersplenism that's associated with platelet retention. 07:39 So you may have a functional thrombocytopenia. 07:43 The liver is a major synthetic factory. 07:44 It's making a whole variety of proteins as we'll talk about. 07:48 The key amongst those is going to be albumin. 07:50 And with hypoalbuminemia due to synthetic defects in the cirrhotic liver, you will have systemic reduction in oncotic pressure. 07:59 And as a result of that, you will have edema everywhere. 08:02 That's also going to exacerbate the ascites that's going on well, liver metabolizes, bilirubin. 08:08 It metabolizes heme to bilirubin and beyond. 08:12 And when the liver is not doing its job in that respect, the patient will be jaundiced. 08:16 There will be coagulopathy, liver is the major source for circulating coagulation factors. 08:22 And when the liver is dysfunctional, as in cirrhosis, you will tend to have bleeding. 08:27 And then with elevated ammonia and other metabolites that would normally be activated and diminished by going through the liver. 08:37 You will have encephalopathy, so the patient will have, will be a little bit crazy. 08:42 So let's talk first about those portosystemic shunts and the three main ones that would have you remember or think about are esophageal varices. 08:51 So the portal esophageal systemic vasculature with occlusion of the portal circulation or compromise, then you get dilation of the esophageal varices. 09:04 These are very dilated veins around the distal esophagus and they just have a very minimum epithelium over the surface they're very easily eroded into and you can have fatal exsanguination from esophageal varices. 09:19 Something called the Caput medusae, literally the head of the Medusa will occur with portal umbilical anastomoses, and then you get this very dilated venous vasculature around the umbilicus and it's been likened to all of the serpents coming off the head of Medusa. 09:40 And then you can have external and internal hemorrhoids that are also part of the portosystemic anastomosis and so you may have rectal bleeding associated with very prominent varices in that location. 09:53 The other secondary effects. 09:54 So, the liver besides making coagulation factors, and besides making albumin, makes transport proteins. 09:59 makes transport proteins. 10:01 So things that will transport fat, or sex hormones or thyroxine and retinol are also affected, so that you may not have normal amounts of those proteins and abnormal circulation to the things that would normally bind to them. 10:18 There's abnormal hepatic glucose metabolism, you're not able to make and store glycogen. 10:24 So the patient may actually have a functional glucose deficiency because there's not a sufficient, sufficient glycogen stores during fasting. 10:37 On the other hand, the abnormal glucose metabolism may also lead to insulin resistance and even exacerbation of a diabetic state. 10:46 And then you can have impaired metabolism of estrogen and the precursors to a number of estrogenic agents and so you are not metabolizing those and breaking them down. 10:56 And patients who have cirrhosis may present with hyperestrogenism. 11:00 We'll talk about that in a moment.

About the Lecture

The lecture Cirrhosis: Epidemiology and Pathophysiology by Richard Mitchell, MD, PhD is from the course Disorders of the Hepatobiliary System.

Included Quiz Questions

Which of the following is the best definition of cirrhosis?

- End-stage liver damage with architectural and functional distortion due to liver fibrosis

- Early-stage liver damage with architectural and functional distortion

- Early-stage liver damage with architectural and functional distortion due to revascularization

- End-stage liver damage with architectural and functional distortion due to revascularization

- End-stage liver damage with architectural and functional distortion due to atherosclerosis

What statement about the epidemiology of cirrhosis is true?

- It is more common in men than in women.

- It affects 50 per 10,0000 people.

- It affects 10 million people in the USA.

- It is the fifth-most common cause of death in the USA.

- It is the sixth-most common cause of death in the USA.

What are the three most common causes of cirrhosis? Select all that apply.

- Viral hepatitis

- Alcoholic liver disease

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Autoimmune disease

- Wilson disease

What is the liver's version of macrophages?

- Kupffer cells

- Stellate cells

- Disse cells

- Endothelial cells

- Hepatocytes

Which cells are responsible for regenerating hepatocytes after liver injury?

- Stellate cells

- Disse cells

- Kupffer cells

- Endothelial cells

- Macrophages

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

1 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

1 customer review without text

1 user review without text