Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

The APC Gene in Colorectal Cancer

-

Slides CP Neoplasia Etiology of genetic alterations.pdf

-

Reference List Pathology.pdf

-

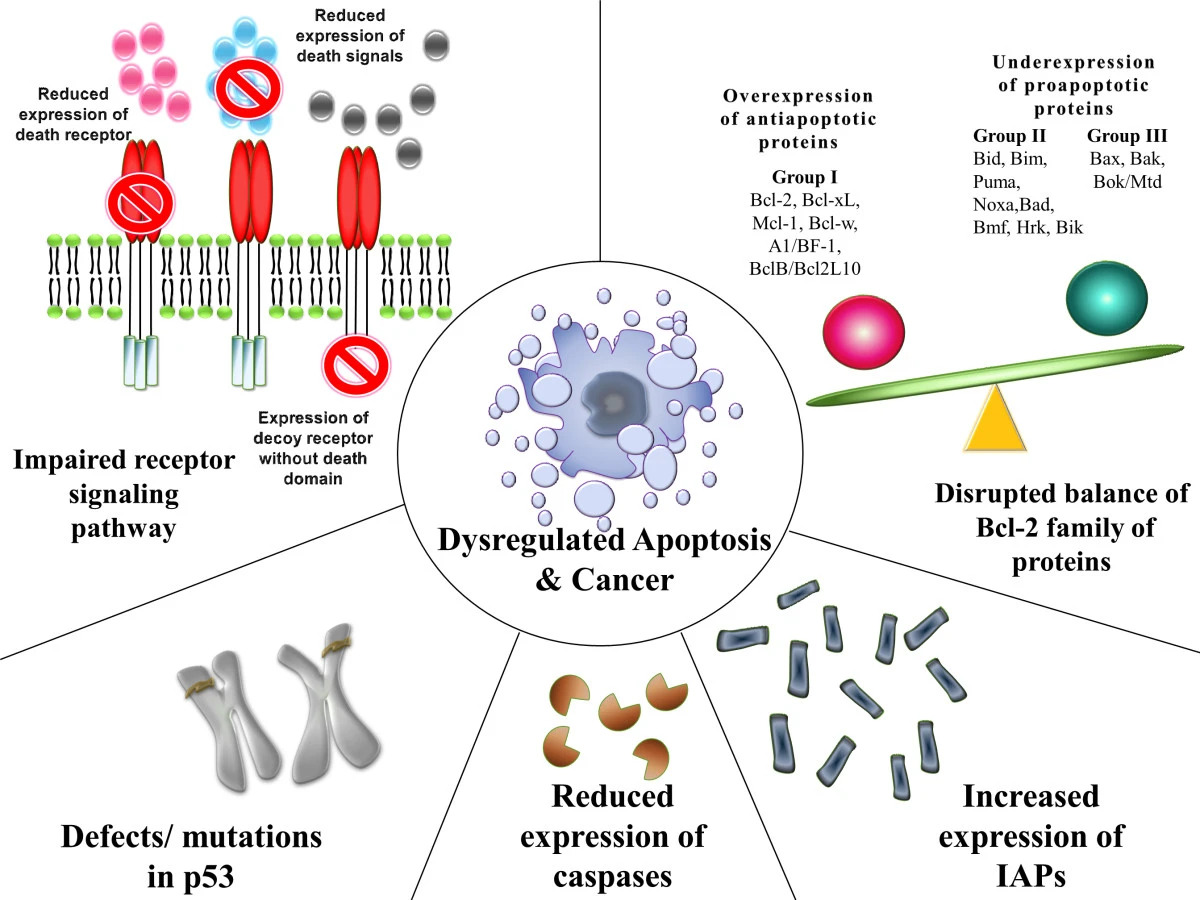

Download Lecture Overview

00:00 So the progression to malignancy is important, it's not a one-hit process. It takes a long time and multiple hits and we often have to involve both tumor suppressor gene mutations as well as oncogene mutations as well as mutations that allow the reactivation of telomerase and mutations that prevent apoptotic cell death, all of those things they have to happen. So let's look. This is from a paper by Vogelstein, it's so called Vogelgram that you may hear about and we're going to start with a normal colonic epithelium on the left hand side and we're going to acquire some hits. Now, I'm going to show you a progression here, it's not always in that stereotyped this had happened first, this had happened second. They can happen very much out of sequence, but this is just an example of how we progress into malignancy by the acquisition of various mutations. So APC as we've already talked about is a tumor suppressor gene. It's on the long arm of chromosome 5 and that may be one of the initial hits. Now it can be a germline hit and people who have adenomatous polyposis coli syndrome or can be acquired mutation. We acquire some tumor suppressor gene mutation, in this case it's APC. Now remember that tumor suppressor mutations are usually autosomal recessive, you need a second hit, but we've already got a cell. Somewhere in the colonic epithelium it's got 1 mutant APC gene. And then, we acquire a second hit on APC or we have a second hit say on the beta catenin gene and so we're going to inactivate both all the normal allyls and now you can see we're ready to get some proliferation, uncontrolled proliferation. Well that's okay, that's not cancer. 02:00 That's just proliferation that's occurring without the necessary stimulus to make it go. 02:05 So we have to have some additional mutations that occur and so then you might have a proto-oncogene mutation say KRAS on the short arm chromosome 12 that will lead now to improved proliferation and start leading to some degree of genetic instability. Okay. If we require additional mutations, we may eventually get a polyp and adenoma. Okay, benign doesn't have all the changes necessary to be considered malignant and especially if we have wild type p53 whenever we go through multiple cycles of turnover and we're going to shorten our telomerase every time and eventually p53 is going to be activated and we will have a senescence. So we will never progress beyond that polyp, but if we mutate now p53 or we have other genes such as mutations and SMAD2, SMAD4 there are whole variety of things. Now we can progress to absolute malignancy and they're probably more genes involved here than just the apparent 2 or 3 that we're talking about, but this gives you a sense of how the progression can occur finally leading to carcinoma. This is only well worked out in the case of colon cancer and even then there are some hand wavy sort of detours that can happen. But want you to be aware that again, and emphasize the point, carcinoma, the generation of cancer is a multi-step process that is associated most commonly ultimately with genetic instability. And with that, we've concluded kind of how cancers occur.

About the Lecture

The lecture The APC Gene in Colorectal Cancer by Richard Mitchell, MD, PhD is from the course Neoplasia.

Included Quiz Questions

Where is the APC gene located?

- Chromosome 5

- Chromosome 6

- Chromosome 4

- Chromosome 3

- Chromosome 2

How can wild-type p53 prevent the progression of an adenoma to a carcinoma?

- Oncogene-induced senescence

- Suppressor-induced senescence

- Suppressor-induced replication

- Oncogene-induced replication

- Apoptosis

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |