Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Restrictive Lung Disease: Introduction

-

Slides RestrictiveLungDisease RespiratoryPathology.pdf

-

Reference List Pathology.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

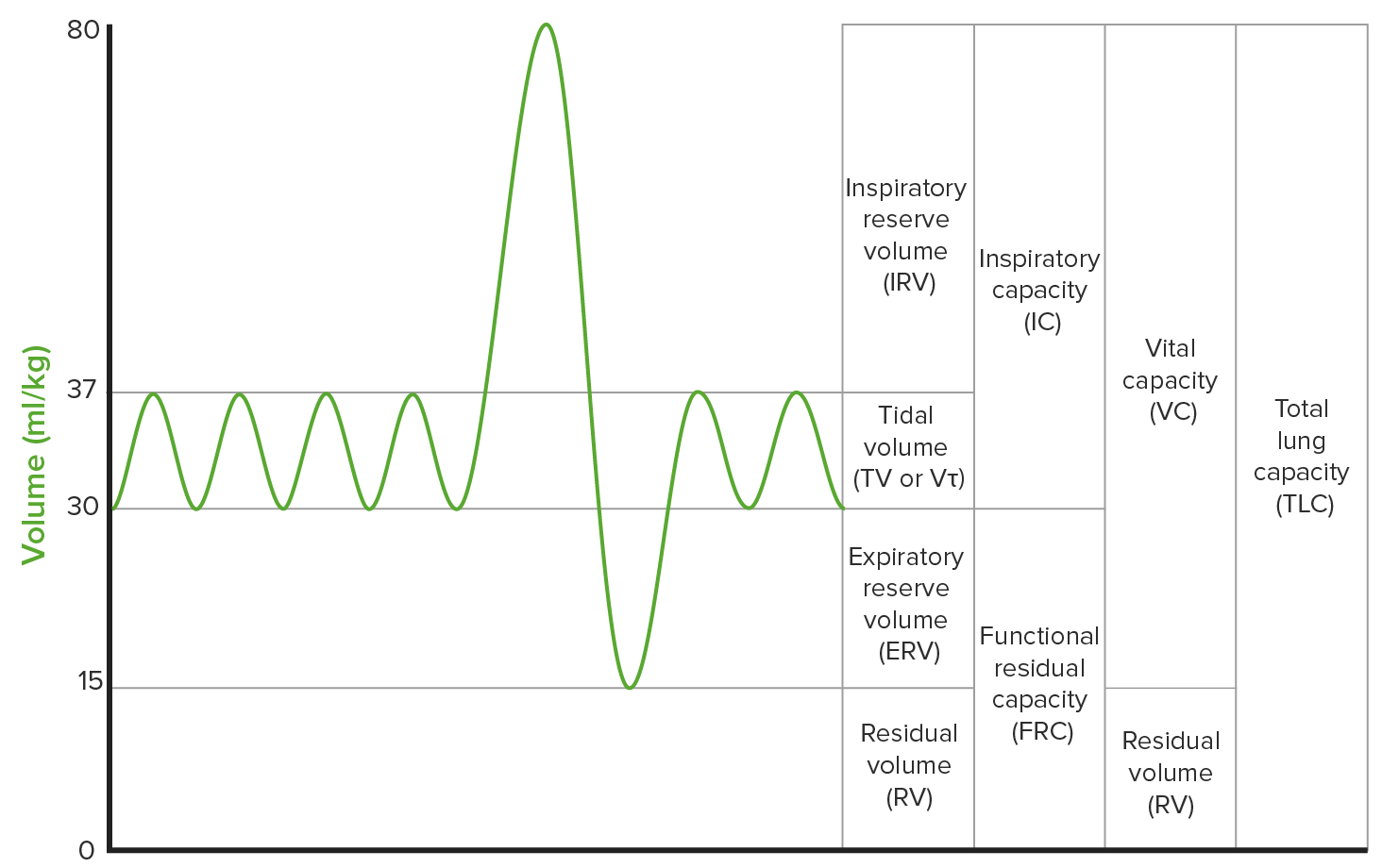

00:02 We’ll now take a look at the category of restrictive lung diseases. When we continue through our differentials of restrictive lung diseases dealing with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or, well, we'll give you the definition and criteria of Usual Interstitial Pneumonia, often times abbreviated as IPF or UIP, as you shall see repeatedly, then it’s the fact that the lung here is extremely non-compliant, it is stiff and we’ll go through a number of differentials in which it will give you this clinical picture. 00:37 Now, with restrictive, what is happening? The fact that the lung is not expanding properly, why? Maybe there is increased fibrosis. So therefore, first and foremost, whenever there’s lung disease, tell me about your forced vital capacity? It is always decreased. 00:54 What does that mean? Well, in obstructive, you tell me about FVC. It is also decreased. 01:01 In obstructive, tell me about TLC. In obstructive, it is increased. In restrictive, your TLC is in fact, decreased. Your first major differentiation point between restrictive and obstructive. 01:15 Let us take a look at your pulmonary function test. Whenever your FEV1 to FVC ratio is decreased, for a fact you have obstructive. If however, you don’t find your FEV1 to FVC ratio to be decreased, then you know that you’re probably in the realm of? Good, restrictive. So what becomes really important here, of paramount importance, would be then the history. 01:39 Let’s take a look at two different types, but what’s more important, once again, is understanding as to what kind of test are you performing or what kind of test is being presented to you so that you’re able to properly interpret your situation. Type 1, here, poor breathing mechanics considered to be extrapulmonary. Stop there. What do you mean by extrapulmonary? Well, there might be issues with maybe perhaps the respiratory centre. Maybe it was a nerve conduction problem. Maybe such as Guillain-Barré. Or maybe it was actual mechanical handicap, meaning to say you have something like kyphoscoliosis in which now your thoracic cage becomes quite small, restricting the lung from expanding. 02:29 Now, as a rule of thumb, when you have extrapulmonary issues, your A-a gradient or A-a widening is normal. Keep in mind, some of the parameters that we looked at for A-a gradient to the fact where, well, if a patient is getting older, then you can expect their normal A-a gradient, well, to still be normal, but it increases. And then secondly, if there’s a hospital setting in which your FiO2 has been given with oxygen, so, therefore, there also you would expect your A-a gradient to then increase, but usually, you want to keep your A-a gradient in mind as being between 10 and 20. 03:07 Okay. Now, why is it that extrapulmonary would then be normal if it’s extrapulmonary. It's a pathology. Well, the reason for that, let me give you real quick, something like your respiratory centre that has been knocked out by a opioid. So, the patient’s been taking opioid, maybe perhaps to deal with his or her pain, which, of course, is a big industry. And so, therefore, knocking out the respiratory centre then does what? Results in what kind of breathing pattern? Good, hypoventilation. Bring everything together now. If you have hypoventilation, what then happens to your carbon dioxide? You’re going to retain more, so increased carbon dioxide. Good. Next, what happens to your pH? Your pH is going to decrease, we have now our primary respiratory acidosis. What’s my point? Well, I have just taken you from knocking out the respiratory centre which is your extrapulmonary. 03:54 As far as the alveoli is concerned, well, its oxygen is going to be decreased, hypoventilation. 04:00 And then if that oxygen in the alveoli is decreased, well will there be a decrease in your PO2 meaning to say in your artery? Of course, and they will give that to you, correct? And so therefore, if you have a decreased in both of those compartments, what does the big “A” mean? Alveoli. What does the little “a” mean? Arterial. Do you remember that discussion? So, if both are decreased, understand there’s no widening, thus a normal A-a gradient. But yet you have a pathology. What caused this pathology? Was it drug induced inhibition of your respiratory centre? What else? Well, extrapulmonary poor muscle effect. I told you about nerve conduction issues, demyelinating disorders including polio, myasthenia gravis, Guillain-Barré syndrome or as we have mentioned earlier what if there was a condition which was then resulting your patient having a compromised chest cavity making it difficult for the lung to then expand? Welcome to things like scoliosis or morbid obesity. Obesity has a whole host of issues as you know. If that the type in which your A-a gradient was normal but still restrictive, what do we have here? Another type of restrictive lung disease. This is damage within the lung and by within the lung we’re referring to it as being what? Interstitial lung disease. 05:25 What does interstitial mean? It is not the alveoli, are we clear? Because once you start destroying the alveoli it really wouldn’t make sense initially to call this restrictive. 05:37 With alveoli destructions taking place remember emphysema, that’s obstructive more so. 05:42 So, as a general rule of thumb you want to keep yourself outside of the alveoli maybe in the interstitium. What’s going on in the interstitium? We’ll walk through a bunch of differentials upcoming. Before I get to any of that please understand that say for example there’s fibrosis taking place in your interstitium, you’re going to make it difficult for carbon monoxide to then? Good, pass through the membrane into the pulmonary capillaries, are we clear? Therefore what happens to DLCO? It decreases. 06:12 Next, what if you’re able to fill up the alveoli which you can if the interstitium has now become fibrosed, but that oxygen doesn’t want to diffuse into the artery, the little “a” what am I increasing in this equation? The little bit equation what are you increasing? Good, the big “A” is increasing, the little “a” think of that as remaining constant so therefore, what happens to A-a gradient? Take a look please, widened or increased A-a gradient. Where is my problem? As a rule of thumb when you have an increase in the A-a gradient, pulmonary. Good. In the pulmonary what kind of diseases are we looking at in terms of differentials? Maybe there is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. What happened in this patient perhaps? Well, the patient began by having acute lung injury, okay, acute. Ask you something, what if something occurred over and over. 07:09 Would you call that acute? At some point when you have enough acute what then happens? It becomes chronic. Becomes chronic for example, pancreatitis. 07:19 Acute pancreatitis, well may lead into chronic pancreatitis. What does chronicity mean to you? Chronicity to you should mean repair, repair, repair. Fibroblast, fibroblast, fibroblast. Collagen, collagen, collagen and fibrosis, right? Good. So say that you have repeated cycles of lung injury. Lots of healing taking place, attempting to. You’re laying down a lot of collagen, there you go. That fibrosis that you’re then depositing in the septae is your honeycomb lung. So, what’s your honeycomb lung mean to you? You know what a honeycomb looks like? Close your eyes. It’s a lovely place where the bees go to live and it fills up with honey. You ever had honeycomb honey? It is the best. 08:04 Anyhow, so now that’s what your lung looks like. The septae are very thickened, right? Why? Because of fibrosis. Did that occur quickly? No, repeated cycles of lung injury. 08:17 Now, if you’re having a hard time now, crossing, exchanging your oxygen if hypoxemia, what do the digits look like? The digits, the nails, clubbing. Clear. So, if you have hypoxemia you take a look at the digits and nails, how would you know that your patient over a long period of time is suffering from hypoxemia? What’s clubbing mean? Looks like the nail is then moving upward, isn’t it? Good, move on. 08:46 What are the differentials? We will be spending more time here not to worry. Sarcoidosis, excellent in terms of its differential causing interstitial lung disease. Should be thinking non-caseating granuloma, you should be thinking about African-American female, right? We’ll talk more about that later right off the back. Next, give you little clues here. Respiratory distress syndrome, what’s happening here? What’s NRDS mean to you? Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome and for the most part by definition a premature baby less than 27 weeks would be the most common here causing lack of surfactant we’ll talk more about that later. Respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal more so. 09:26 Pneumoconioses is a big topic for us, we’ll talk about those individuals that are exposed, and exposed and exposed to different occupations and in that occupation maybe they’re working in a mine and they were exposed to coal; maybe they’re working in a mine and apart from coal they were also exposed to silica, are we clear? So these are pneumoconiosis. Take a look at ANCA+. ANCA+ means GPA. Formerly known as Wegener’s, it’s granulomatosis with polyangiitis. What’s MPA? microscopic polyangiitis and what’s EG? Eosinophilic granulomatosis. Do you have every single one of these? Oh yeah, right. So, two of these are going to be pANCA and then one of these will be cANCA. Which two are pANCA? Real quick, MPA and Churg-Strauss. Dr. Raj, you didn’t say Churg-Strauss, yeah I did. I said eosinophilic granulomatosis, got you, joking. Anyhow so keep that in mind eosinophilic granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss that’s pANCA, with me? What about cANCA? GPA. Continue. 10:31 What other differentials, what’s my topic? Interstitial lung disease, your A-a gradient is widened with a decrease in DLCO. Eosinophilic pneumonia we’ll spend time with. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis we’ll be spending time with. Important differentials. Students tend to get these confused, you will no longer do that. So, if you were having issues with obstructive, I hope that is clear as we went through the classifications, current day practice and such and with restrictive you’ll be clear here as well with the various differentials or maybe the interstitial lung disease and restrictive was caused by drugs. For example, bleomycin, nitrofurantoin, amiodarone all these drugs that you should know about in different settings. Maybe your patient required antineoplastic, maybe your patient required treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, maybe your patient required some type of cardioversion right, and so therefore, amiodarone becomes important.

About the Lecture

The lecture Restrictive Lung Disease: Introduction by Carlo Raj, MD is from the course Restrictive Lung Disease.

Included Quiz Questions

Which of the following findings is seen in restrictive lung disease?

- FEV1/FVC ratio equal to or greater than 80%

- Increased FVC

- Increased TLC

- FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 80%

- Increased RV

Which of the following restrictive lung diseases will show a normal A-a gradient?

- Guillain-Barre syndrome

- Pneumoconiosis

- Churg-Strauss syndrome

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Which of the following restrictive lung diseases would show an elevated A-a gradient?

- Pneumoconiosis

- Morbid obesity

- Polio

- Guillain-Barre syndrome

- Myasthenia gravis

Which of the following drugs can cause restrictive lung disease?

- Amiodarone

- Amoxicillin

- Acetaminophen

- Amitriptyline

- Amlodipine

A 72-year-old man comes to the ER with difficulty in breathing. His pulmonary function tests show an increase in the FEV1/FVC ratio, a decrease in DLCO, and an increase in the A-a gradient. Digital clubbing is noted on physical examination. Which of the following is the most likely pathological etiology?

- Repeated cycles of lung injury and collagen deposition

- Autoantibody production

- Immunosuppression

- Repeated cycles of lung injury and calcium deposition

- Granuloma formation

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |