Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Peritoneum: Definitions

-

Slides Peritoneum Definitions.pdf

-

Reference List Anatomy.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

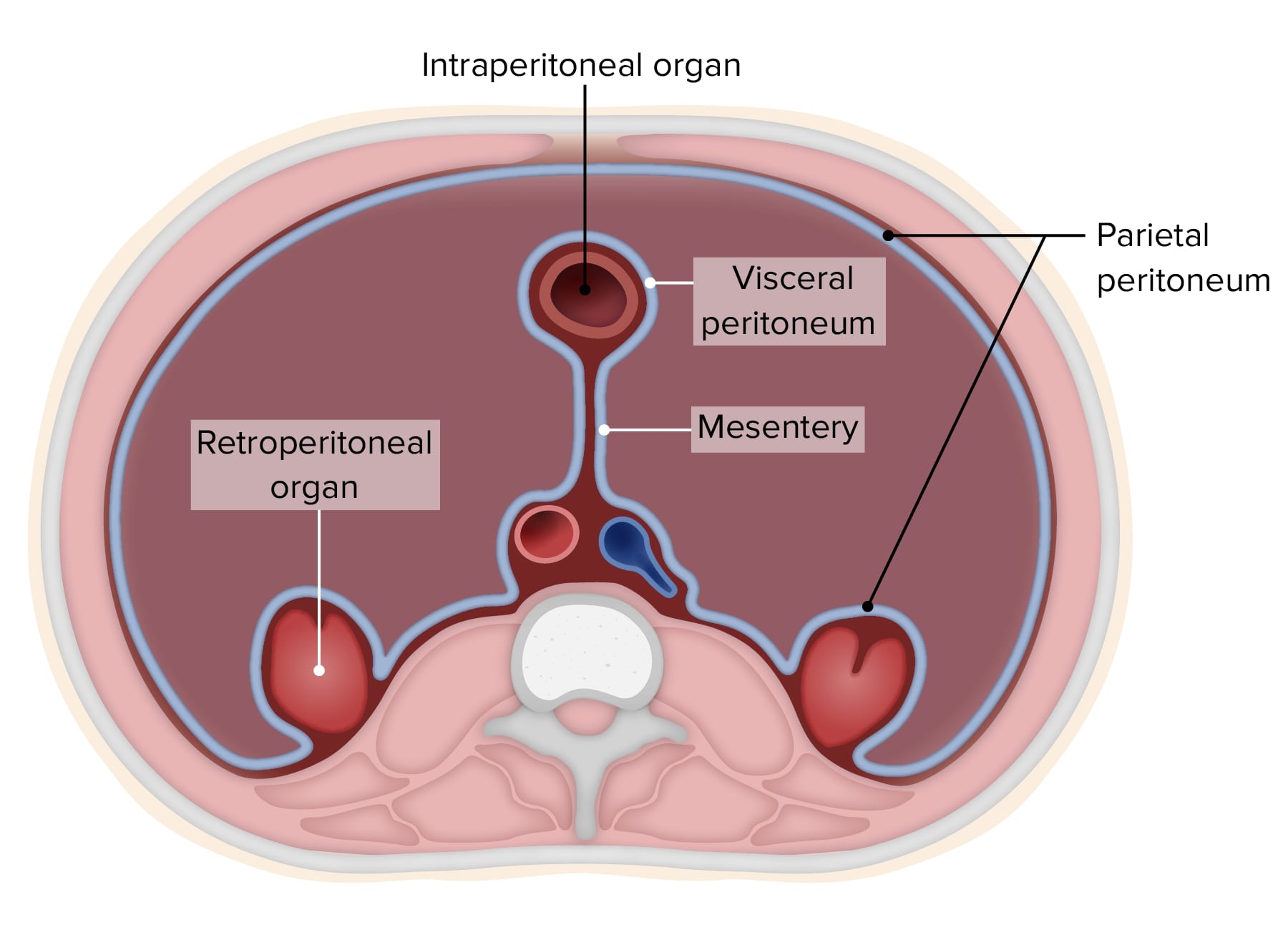

00:01 Let's carry on with a few more of these definitions. So here we've got our visceral peritoneum and here we've got our parietal peritoneum. We've got a retroperitoneal organ being the kidney and we have an intraperitoneal organ being the small intestine, a piece of jejunum or ileum, for example. Where we have that layer of peritoneum that actually leaves the small intestine and runs to the posterior abdominal wall, we have a double layer. So you can imagine as we go over the left kidney, we have a portion of peritoneum that runs over the left kidney. It then leaves the abdominal wall to go and encapsulate all of the small intestine. As it comes back around the small intestine, it then returns to the posterior abdominal wall. Now we've got these 2 layers that are pushed together. This is called a mesentery, a double layer of peritoneum. 00:57 Hopefully now you can imagine that with this double layer of peritoneum, it actually forms a root and this helps to give that small intestine a great deal of mobility which of course is important as the passage of food is being digested and absorbed as it passes all the way through the gastrointestinal tract. During embryological development, all of the gastrointestinal tube was one continuous floating suspended by mesentery tube. 01:29 But as the small intestine grew a much faster pace than the large intestine and the small intestine occupied that much bigger location within the central portion of the abdomen, it actually force the colon or the large intestine laterally and that's why we can see the large intestine actually pushed to the lateral margins of the abdomen. And what actually happened here is the colon, which we can see, is also suspended by a piece of mesentery. But as the small intestine got bigger and bigger, so the large intestine indicated here by the colon on both the left and the extreme right side was pushed laterally, and that's where we see it today in the adult human. And as it kept getting pushed and pushed, it lost its mesentery. If we go back a couple of slides, you can see how it has a mesentery. And then as the small intestine expands, expands, expands, it gets pushed laterally and it actually blends with the posterior abdominal wall. And that mesentery is lost. 02:33 Now because of this, it is a retroperitoneal organ, but because it's started off by having a root of mesentery, it was suspended and due to the small intestine increasing in size, so the large intestine got pushed to the lateral margins and so lost its mesentery. It's now a retroperitoneum organ but we distinguish it from other retroperitoneal organs like the kidney by calling it secondarily retroperitoneal because it did start with a mesentery. Now let's have a look at this in a slightly different way. Instead of looking at it as if we'd made a transverse section and now we're looking at the person through that feet, let's have a look at this as if we were to do a sagittal section through the cadaver. 03:22 So on the right hand side of the screen, we have the vertebral column. On the left hand side, we have the anterior abdominal wall. And we've made a sagittal section through the liver. You can see there we have L, stomach S, transverse colon, aorta, pancreas, duodenum, and the small intestine. We can see those structures. And what we can see is the peritoneum actually investing itself all the way around these organs. So here we can see the stomach and if we just go to the bottom where the small intestine is located, we can see that double layer of peritoneum. We can see there are 2 lines as indicated by the black dot indicating the mesentery. There are 2 blue lines and that's because it's a double layer of peritoneum passing down around the small intestine and then back to the posterior abdominal wall. This is the mesentery. 04:15 It suspends the small intestine. When I spoke previously about the large intestine being pushed laterally, I didn't mention the transverse colon because the transverse colon, remember, was pushed upwards and this piece of the colon retains the mesentery. So that piece wasn't pushed laterally and forced to become secondarily retroperitoneal. The transverse colon therefore maintains the mesentery. What do we call this mesentery? We call it the transverse mesocolon. So it's transverse for the transverse colon, it's meso for mesentery, transverse mesocolon. 04:56 The mesentery of the transverse colon and we can see that there. If we also do have a look at the liver, the liver is associated with the peritoneum and here we can see how the liver actually develops within what's called the ventral mesentery. You should look at that in some embryology textbooks. It's a remnant of the ventral mesentery, which is a piece of mesentery that connects to the primitive gut tube to the anterior abdominal wall. Then as the gastrointestinal tract rotated to the right, so the liver became situated on the right side. And it retained its peritoneal attachments. So here we can see how the liver is pushed off against the diaphragm and retains some of those peritoneal attachments. If we follow it from the anterior abdominal wall, we can see it passes up on the side of the diaphragm and then runs towards the liver where it then runs along the anterior surface of the liver. That little connection between the diaphragm and the liver at the top is known as the anterior coronary ligament. A similar thing happens on the posterior aspect where we can see the posterior aspect of the liver and the posterior abdominal wall. The liver is connected at that point by the posterior coronary ligament. And this is really important because they help to suspend the liver in position and help to prevent it falling down into the abdomen. It's suspended from the diaphragm by the anterior and posterior coronary ligament. We have another piece of peritoneal attachment that's running from the liver to the duodenum and the stomach. And this is known as the hepatoduodenal ligament and the hepatogastric ligament. So a connection of peritoneum from the liver to the duodenum is the hepatoduodenal ligament and a connection of the liver to the stomach is the hepatogastric ligament. We'll come to that in a little while later when we talk about the lesser omentum because now we can see on the screen we have a greater omentum. Now a greater omentum is a remnant of these peritoneal foldings and outpouchings of various twists and turns that GI tract takes during embryological development. And what we can see is the greater omentum is formed by 2 double layers of peritoneum when it's below the transverse colon. So here coming away from the stomach, we can see 2 layers of peritoneum that's surrounding the stomach. They then converge to go down as the anterior layer of the greater omentum to then come back up and go over the transverse colon as another double layer. This is the posterior layer of the greater omentum. So we can see leaving the stomach and descending, we have 2 layers of peritoneum forming the anterior parts of the greater omentum. It gets to the bottom of the greater omentum before it comes back up as another double layer and then heads towards the posterior abdominal wall. 07:55 You can just about make out then the connection of the transverse mesocolon so you can see between the stomach and the transverse colon, there are actually 6 layers of peritoneum; 2 from the stomach going down, 2 coming up as the posterior layer of greater omentum going over the transverse colon, and then 2 layers of the transverse mesocolon. So there we actually have 6 layers of peritoneum. I spoke about the greater omentum. We have the 2 layers going over the stomach coming down forming the greater omentum and here we have 2 layers of the stomach and what will be part of the duodenum going to the liver and that is the lesser omentum, which has those 2 gastrohepatic and gastroduodenal ligaments.

About the Lecture

The lecture Peritoneum: Definitions by James Pickering, PhD is from the course Peritoneum and Peritoneal Cavity.

Included Quiz Questions

What is the peritoneal cavity?

- Space between visceral and parietal peritoneum

- Area within the stomach where digestion begins

- Layer of muscle lining the abdominal wall

- Duct that connects the liver to the small intestine

- Membrane surrounding the lungs and heart

Which of the following organs is intraperitoneal?

- Spleen

- Duodenum

- Kidneys

- Pancreas

- Esophagus

Which organ does the falciform ligament attach to the anterior abdominal wall?

- Liver

- Spleen

- Stomach

- Pancreas

- Gallbladder

Which statement describes the mesentery?

- It contains nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics.

- It is derived from visceral peritoneum and parietal peritoneum.

- It is derived from remnants of Rathke's pouch.

- It attaches one organ to another.

- It contains only blood vessels.

Which of the following structure(s) is secondarily retroperitoneal?

- Ascending and descending colon

- Bladder

- Suprarenal glands

- Ureters

- Kidney

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |