Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Pericarditis: Diagnosis

-

Slides Pericarditis InfectiousDiseases.pdf

-

Reference List Infectious Diseases.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

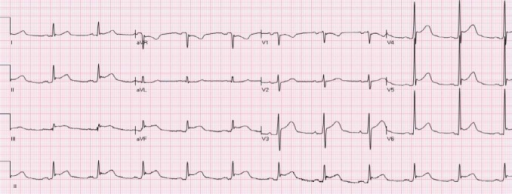

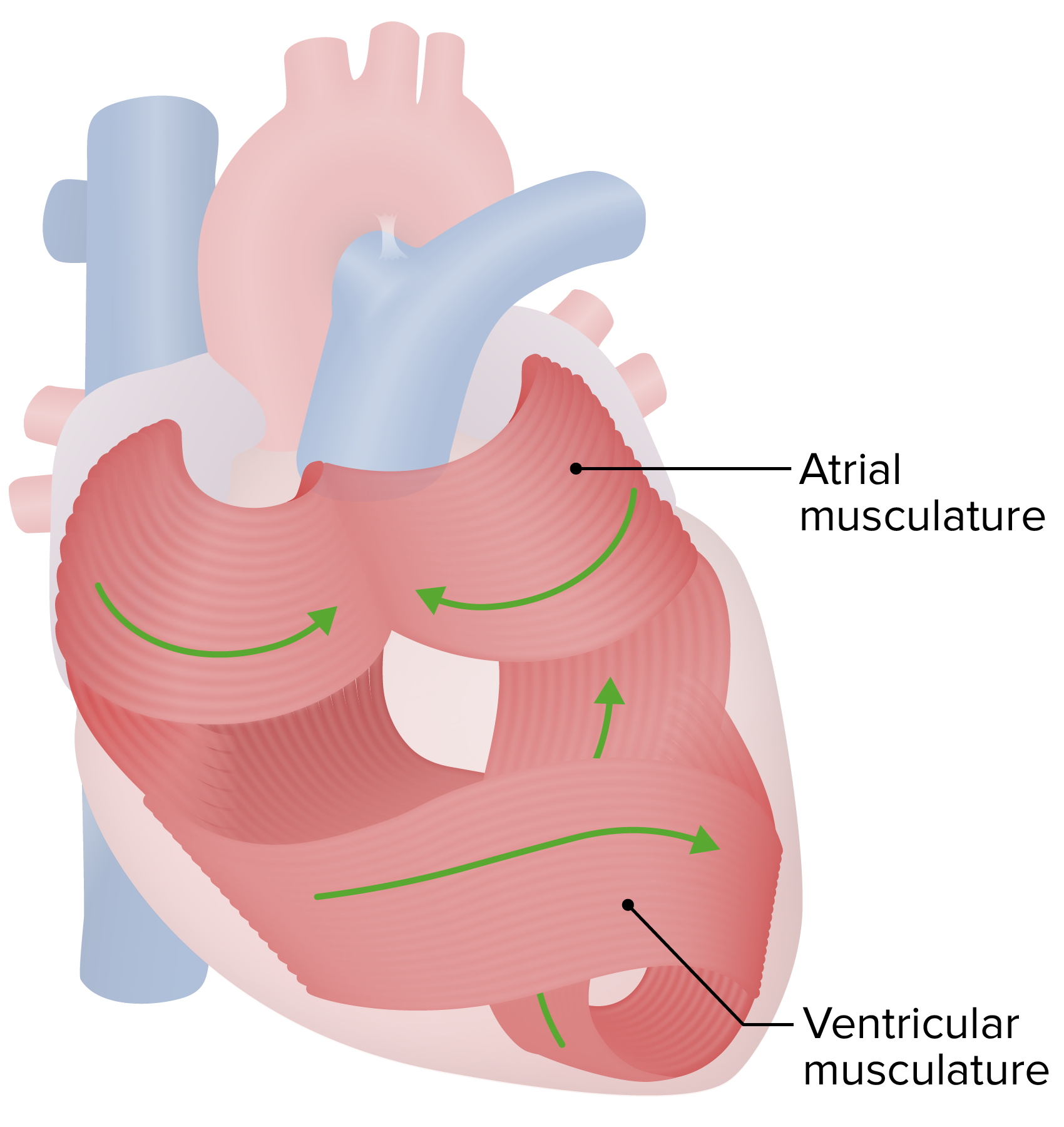

00:01 In terms of making a specific diagnosis, we’ve got to find out what’s in the fluid. Now, if the patient is only mildly ill, you probably would not do a pericardiocentesis. But if the patient is substantially ill, you’ve got to get some of that fluid for stains and culture. Once again, you wouldn’t put a patient through such a procedure without getting the maximum yield from the procedure. So, simply to culture it for routine bacteria would hurt the patient. If you’re going to do such an invasive procedure, you’re going to do stains and cultures, I like to say for everything known to man, for routine bacterial stains and cultures, as well as for AFB and fungi. 00:51 And while you’re at it, to rule out malignancy, you would want to get cytology on the fluid. 00:58 The analysis of the pericardial fluid also checks the level of glucose, protein, LDH, cell count with differential and also serum compliment. 01:06 Special tests can include tumor markers and PCR, for mycobacterium tuberculosis if TB is suspected. 01:14 Sometimes when the fluid is substantial and a pericardial window must be placed to drain the fluid by the cardiac and chest surgeons, you want to go ahead and get a pericardial biopsy. 01:30 because actually having a large amount of tissue increases the yield for determining the cause. 01:37 So, pericardiectomy with biopsy and drainage when there’s need for doing an invasive procedure. 01:48 It’s going to produce higher yield and fewer complications than sticking the pericardium. 01:55 A specific diagnosis can generally be made in at least half the patients. Keep in mind that many of these are caused by viruses which we are unable to identify. So, how do you treat pericarditis? When acute pericarditis is of presumed viral cause, an echocardiogram should be done to assess the amount of effusion and to exclude significant myocardial involvement and constriction. 02:26 Colchicine with aspirin or another NSAID is recommended at the onset and the NSAID is gradually discontinued when pain resolves and CRP normalizes. In acute pericarditis following myocardial infarction, aspirin plus colchicine is the preferred treatment. 02:45 Other NSAIDs and glucocorticoids should generally be avoided unless necessary. The most common adverse event of colchicine (5-8%) is GI intolerance. Systemic corticosteroids (i.e., prednisone) have been used mostly as second- or third-line treatments. A meta-analysis showed that high-dose corticosteroids, once frequently prescribed, are associated with an increased risk of recurrence and prolonged disease and showed that low-dose therapy was associated with lower rates of recurrence and treatment failure. 03:21 Lifestyle modification is an important element of routine management especially in athletes who should return to competitive sports only after symptoms and diagnostic tests have resolved with a minimum restriction of three months. This is because of the detrimental effects of exercise-induced tachycardia and its shear stress on the pericardium which may worsen inflammation. 03:46 Hospitalization is advised for patients with fever over 38C, hypotension, echocardiographic evidence of large effusions, wall motion abnormalities, or constriction. Admission is also advised for patients receiving anticoagulation or immunosuppressive agents. Pericardiocentesis is generally recommended for hospitalized patients and the fluid should be submitted for special stains, routine, AFB, and fungal culture. 04:17 When the cause of pericarditis remains unclear, a pericardial biopsy and fluid cytology are indicated. 04:25 Empiric therapy using the combination of an anti-staphylococcal agent such as vancomycin plus ceftriaxone for respiratory pathogens such as S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae, and Gram-negative bacilli as well as to cover the possibility of MRSA. 04:43 Antimicrobial therapy is then tailored to the results of cultures and microscopy. 04:48 Intravenous antibiotics should be continued until all clinical signs have resolved and WBC counts are normal. 04:56 Tuberculosis should be especially considered when the onset of symptoms has been subacute because of the genuine concern for constrictive pericarditis. 05:09 The incidence of tuberculous pericarditis is particularly high in patients with HIV infection. 05:13 Tuberculous pericarditis results from hematogenous spread to the pericardium during primary infection or from contiguous infection in hilar nodes, lung parenchyma, or pleura. For cardiac tamponade, we certainly need to do pericardiocentesis emergently if it’s an emergent problem or put an intrapericardial catheter for one to two days for acute infectious pericarditis and then withdrawing the catheter should be able to do something with that. 05:48 For healed pericarditis, you can get a plaque-like, fibrous thickening of the serosal surface, so called soldier’s plaque. That doesn’t usually have any effect on cardiac function. 06:05 Complications of pericarditis include adhesive mediastinopericarditis and constrictive pericarditis. 06:12 In adhesive mediastinopericarditis, the pericardial sac is often completely obliterated, which can compromise cardiac contraction. 06:21 Constrictive pericarditis results in a dense, fibrous, or fibrocalcific scar, sometimes with calcium deposits in the pericardial sac, significantly limiting diastolic filling. 06:33 In such cases, a pericardiectomy is required, which involves meticulous surgical intervention. 06:40 Of course, that brings me to the end of my discussion of pericarditis. I hope it helped.

About the Lecture

The lecture Pericarditis: Diagnosis by John Fisher, MD is from the course Cardiovascular Infections. It contains the following chapters:

- Pericarditis – Diagnosis

- Pericarditis – Management

Included Quiz Questions

Which of the following diagnostic evaluations is NOT generally helpful in the analysis of pericardial fluid?

- Differentiating transudative from exudative pericardial effusion

- Bacterial and fungal culture

- Gram stain

- Cytology

- Polymerase chain reaction

Which of the following is the most appropriate treatment for acute idiopathic or viral pericarditis?

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicine

- Corticosteroids

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids

- Colchicine and corticosteroids

- Antiviral medications

What is the definitive treatment option for patients with chronic constrictive pericarditis who have persistent and prominent symptoms?

- Surgical pericardiectomy

- Percutaneous pericardiocentesis

- Long term antibiotic therapy

- Long term corticosteroid therapy

- Cardiac transplant

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |