Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Myocardial Infarct: Healing and Granulation of Tissue

-

Slides Complications of Atherosclerosis.pdf

-

Reference List Pathology.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

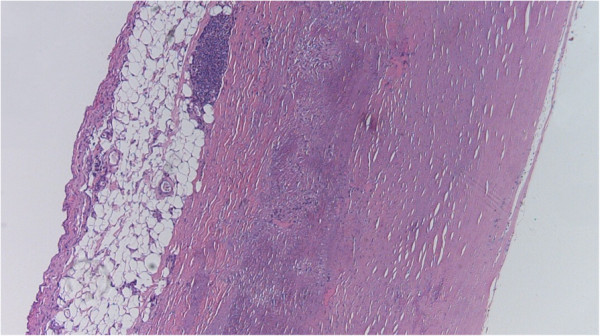

00:01 So let's talk about what this actually looks like. 00:04 So we are looking at a transverse slice of a heart. 00:08 The thinner wall on the upper left hand side, that's going to be the right ventricle. 00:12 Then we have the interventricular septum, we've got the complete doughnut of the left ventricle. 00:16 And in this slide, we can see that there is an area of dark red brown in the posterior septum. 00:23 This would represent an area of a right coronary artery infarct, probably reasonably proximal, that has since been reperfused. 00:34 That's why it looks hemorrhagic and brown. 00:36 And that's recognizable about 24 hours, particularly because of the hemorrhage. 00:41 What's going to happen grossly after 7 to 10 days, we'll work on it. 00:46 As we have talked about in a separate session, when we're talking about wound healing and the healing of necrotic tissue and things like that, we will begin to develop granulation tissue at about 7 to 10 days. 00:59 That granulation tissue is early neovascularisation to provide a provisional stroma, provisional matrix upon which we're going to lay down scar. 01:09 It's actually at this time point, 7 to 10 days, that the heart is particularly vulnerable to other complications. 01:16 If you think about it in this transmural infarct, granulation tissue is peaking at about that time point 7 to 10 days. 01:24 Wow, granulation tissue doesn't look anything like myocardium. 01:28 It doesn't have a lot of connective tissue in it yet, doesn't have any myocardium at all, because it's all been destroyed. 01:35 At that 7 to 10 day time point, that part of the wall that has had a transmural infarct is prone to rupture. 01:41 We'll see pictures of that. 01:43 And classically, if we're going to have a myocardial rupture after transmural infarct, it's going to occur in that timeframe and that's because we have the peak of granulation tissue. 01:54 And then finally, if the patient survives, and that's what we're hoping, that granulation tissue in that area will turn into a dense fibrous scar. 02:04 Now at that time point, that fibrous scar, that's a lot of collagen, that's never going to rupture. 02:10 Unfortunately too, that is never going to squeeze. 02:13 Collagen just doesn't contract the same way that the myocardium contracts. 02:17 So the rest of the heart will have to undergo some degree of compensatory hypertrophy in order to maintain cardiac output. 02:26 Not only that, but that area of fibrosis, that's now that scar in the area of the infarct will tend to remodel. 02:34 You can already see even on this slide, that the thickness of the wall there is much thinner than the normal myocardium. 02:42 That's because the pressures that are generated by the rest of the heart squeezing will cause remodeling of that matrix and it actually is like a weak spot on an inner tube, that kind of pouches out. 02:53 And that area can form an aneurysm, and we'll see that in a subsequent slide as well. 02:59 Let's look now, this is grossly. 03:01 Let's look at what this looks like histologically. 03:05 Here we have our first panel. 03:07 Normal myocardium. 03:08 Not completely normal, the cells, the nuclei are a little bit big, but basically this is normal healthy myocardium with intact basophilic nuclei. 03:19 Everything looks wonderful. 03:20 The little lines of small red dots, those are capillaries going in between the myocytes. 03:25 Everything is hunky dory. 03:27 Okay, now we're going to damage that irreversibly. 03:30 In about 12 to 24 hours, we have coagulation necrosis. 03:35 And again recall from other sessions that we've been in together, what coagulation necrosis looks like? It still looks fundamentally like normal myocardium except they are of no nuclei. 03:46 We've had breakdown of the nuclear material, karyolysis. 03:51 And we're also starting to recruit now as you see there, a lot of neutrophils into the tissues. 03:57 As early as 12 to 24 hours, neutrophils will come in from the nearest viable myocardium. 04:04 By 1 to 2 days, we are in full blown neutrophilic infiltrate, and they are beginning the process of breaking down the cardiac myocytes. 04:13 Cardiac myocytes by themselves cannot really break themselves down very well. 04:17 They don't have enough lysosomal content to degrade all the proteins. 04:20 So to break down dead myocytes we need those neutrophils. 04:24 And by 1 to 2 days, it's pretty much not exclusively, but pretty much wall to wall neutrophils. 04:31 By 2 to 3 days, we've switched over into a macrophage predominant population. 04:38 Neutrophils as you recall, are short lived. 04:41 1 to 2 days, that's kind of it. 04:43 So once we get that wave of neutrophils as they come in, they will fade away. 04:47 They will undergo apoptosis and die, but they will have set the stage now for macrophages to come in, who will be the definitive cleanup crew and will start the process of healing this area of necrosis by driving the neovascularisation, the granulation tissue to come in. 05:06 So at this point, the myocytes are mostly but not exclusively, completely chewed up and broken down. 05:12 Macrophages will finish the job. 05:14 And we now have mostly mononuclear cell infiltrates. 05:18 By 7 to 10 days, most of the dead myocytes are gone. 05:23 And what we have instead is a relatively increased population of macrophages that are now orchestrating the ingrowth of new blood vessels and beginning the process of bringing in fibroblasts that are going to lay down matrix. 05:38 So this is that that time period at about a week to 10 days after an infarct when we have granulation tissue. 05:46 And then on this provisional stroma, the granulation tissue, we will develop scar. 05:51 And by 4 weeks, all the stuff that had been dead at 12 to 24 hours is now collagenized. 05:58 It's a scar, it won't rupture. 06:01 As opposed to that, that's material at 7 to 10 days. 06:03 It won't rupture but it also is definitely not contractile. 06:07 And so it's a trade off and we can't just leave necrotic myocardium there either. 06:13 Okay, so that pattern.

About the Lecture

The lecture Myocardial Infarct: Healing and Granulation of Tissue by Richard Mitchell, MD, PhD is from the course Atherosclerosis.

Included Quiz Questions

What is a late outcome of myocardial infarction?

- Compensatory hypertrophy

- Reperfusion

- Hemorrhagic color to the tissue

- Formation of granulation tissue

- Myocardial rupture

When does the disintegration of the cardiac myocytes take place?

- 1–2 days

- 12–24 hours

- 2–3 days

- 7–10 days

- > 4 weeks

Which stage of a healing infarct shows neocapillary invasion?

- Granulation tissue formation

- Coagulation necrosis

- Neutrophil migration

- Macrophage migration

- Scar tissue formation

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |