Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Alcoholic Liver Disease: Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

-

Slides GIP Alcoholic Liver Disease.pdf

-

Reference List Pathology.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

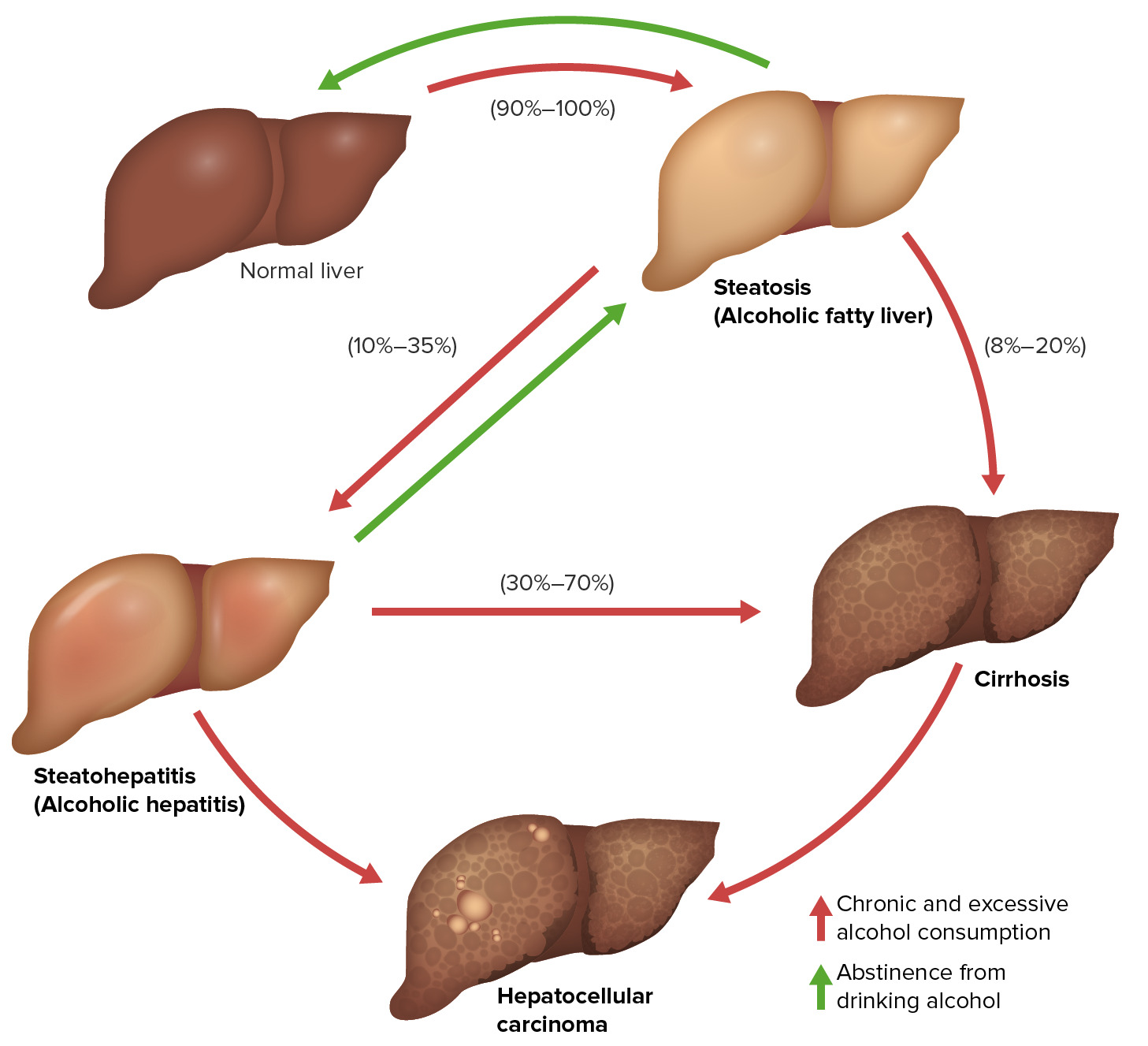

00:01 Welcome. 00:02 In this talk, we're going to cover various aspects of alcoholic liver disease. 00:07 This is an umbrella term that encompasses everything from alcoholic steatosis or fatty liver, which is reversible entity to steatohepatitis, which involves inflammation in association with steatosis, which can also be reversible. 00:22 And then finally to end stage cirrhosis, which is irreversible. 00:27 And all of this is secondary to alcohol, misuse or abuse. 00:33 When we talk about the pathophysiology of alcoholic liver disease, we're fundamentally talking about three stages. 00:39 Starting with a completely normal liver, and a little overindulgence in alcohol in the vast majority of people will result in a fatty liver or steatosis. 00:49 This is reversible, and with abstinence, that will revert completely back to normal. 00:55 In a smaller subset of patients who develop steatosis or have recurrent bouts of steatosis, related to alcohol intake, they will develop inflammation. 01:06 In association with a fatty liver, which will present a steatohepatitis, so there will be inflammation. 01:13 This is also reversible, and can revert back to a completely normal liver with abstinence. 01:20 However, in a subset of those patients, either due to endogenous kind of genetic foundations, or because of recurrent injury along this pathway, patients with standard hepatitis can develop cirrhosis. 01:37 Once you have cirrhosis, you are at increased risk for developing hepatocellular carcinoma, and all the other complications associated with cirrhosis. 01:46 In addition, a certain subset of patients who steatohepatitis will also develop potentially hepatocellular carcinoma. 01:56 The epidemiology overall. 01:59 Alcohol use disorder in the United States is a rampant entity, maybe 1/5 of the population is using alcohol to excess. 02:11 It is the second most common cause of cirrhosis in the United States, only exceeded by non alcoholic fatty liver disease. 02:20 The presence or the prevalence of alcoholic fatty liver disease is about 4% of the newest population. 02:26 So not everyone who abuses alcohol will get alcoholic fatty liver disease, but a substantial proportion of individuals will. 02:35 In alcoholic hepatitis also develops in a roughly a third of the alcoholics. 02:42 Risk factors. 02:43 So women tend to have an increased susceptibility, this has to do with estrogens and the metabolism rate for most women as they break down alcohol. 02:53 If there is concurrent infection or other trauma to the liver, this will increase the risk of developing alcohol related steatohepatitis and or cirrhosis. 03:03 So hepatitis C concurrent infection will also increase your risk. 03:09 Obesity and non alcoholic fatty liver disease by virtue of giving a second independent hit outside of the alcohol toxicity will also increase the risk of developing the other complications associated with alcohol use. 03:24 A high fat diet, smoking and diabetes also because they are providing additional hits to the poor unfortunate liver will also increase the risk of developing complications. 03:36 In terms of the pathophysiology, we have to understand some of the metabolism. 03:41 The main causative factor and is heavy alcohol consumption. 03:44 And in general, in men, this is greater than 440 grams a day or four mixed drinks per day. 03:51 In women, greater than 20 grams per day, or two mixed drinks per day. 03:57 To understand what goes on with alcohol, you have to understand what goes on with the metabolism. 04:02 And ingestion of alcohol is usually degraded in the liver through the activity of alcohol dehydrogenase or ADH, converting it to the intermediate precursor acetaldehyde. 04:13 There may be a component involved of catalase activity, but the ADH pathway is predominant and will require the reduction of an oxidized form of nicotine adenine dinucleotide or NAD. 04:26 That acetaldehyde is then rapidly converted by aldehyde dehydrogenase to acetate, which can then enter the TCA cycle and be involved in other intermediary metabolism. 04:37 Again, aldehyde dehydrogenase requires the reduction of NAD to NADH. 04:45 That's the normal pathway and if you have moderate alcohol intake, this is more than sufficient to metabolize all the alcohol relatively quickly and efficiently to acetate. 04:56 But with excess alcohol, But with excess alcohol, we have involvement I have a Cytochrome P450 pathway, which will generate acetaldehyde again, but will involve the formation of reactive oxygen species. 05:11 That acetaldehyde still has to be further degraded through aldehyde dehydrogenase to acetate. 05:17 But that alternate pathway with the formation of reactive oxygen species leads to inflammation, and in turn will lead to fibrosis. 05:26 As we are going through this progressive oxidation of alcohol to acetaldehyde, we are using up the normal reducing capacity of the hepatic machinery. 05:42 So, we're using up NADs in order to make acetaldehyde. 05:48 If we do not have adequate NAD, to then do the other metabolic functions of the liver, we will not be able to metabolize lipids, for example, and we won't be able to bite off two carbons from fatty acids to create acetate, we will use all of our NAD to metabolize the alcohol. 06:11 That's why when you have alcohol excess, besides the reactive oxygen species through the cytochrome P450. pathway, you will also not be moving things fat effectively through their normal metabolic pathway. 06:27 So the initial accumulation is of triglycerides of fat. 06:32 So that initial step is reversible. 06:36 So we are transiently using up all of our NADs to metabolize all that alcohol and when the alcohol is gone, then we will turn back and use the NADs for lipid metabolism. 06:48 That's how you can go from a normal liver to a fatty liver and then revert back to a normal liver because we eventually catch up. 06:57 And in the majority of cases with abstinence that's exactly what happens. 07:01 However, with recurrent injury, and or severe accumulation of fat, you can actually drive oxidative damage. 07:11 And this is also going to be exacerbated by the cytochrome P450. 07:15 Reactive oxygen species pathway. 07:18 And now we're going to get steatohepatitis, to get the fat accumulation and we'll have inflammation on top of that. 07:25 Again, if we stop drinking, then the excess fat goes away. 07:31 The reactive oxygen species are damped down by the normal pathways that tamp those into submission. 07:38 And we can revert all the way back to a normal liver. 07:41 But with recurrent bouts of injury, we can progressively accumulate damage to hepatocytes and inflammatory activation, that exceeds our capacity to heal, to regenerate, and to revert and then we get into irreversible cirrhosis. 08:00 So walking through the step by step. 08:02 Decreased NAD, the oxidized form, impairs our ability to undergo lipolysis. 08:08 The swollen hepatocytes that are taking up triglycerides, we will not be able to metabolize them, and we will accumulate that fat within microvesicles. 08:17 The fat infiltration is typically close to the venules. 08:21 That's where we have the limiting amounts of the NAD to begin with. 08:25 And it's being used now for alcohol metabolism. 08:28 And this can happen actually overnight, certainly within two days of excess alcohol consumption. 08:33 And with abstinence, it will resolve within a couple of weeks after the discontinuation of alcohol. 08:42 At the hepatitis stage, there are inflammatory mediators. 08:45 So Kupffer cells within the hepatocytes are feeling the effects of reactive oxygen species generated through the cytochrome P450 system. 08:54 And the effects of excess fat also potentially driving additional reactive oxygen species. 09:00 Those Kupffer cells will generate inflammatory cytokines, which will recruit and then activate neutrophils bringing them in, especially around the central area and a combination of the reactive oxygen species and the cytokines from the inflammatory cells. 09:18 We will get ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, intracellularly because of the change of the redox potential, the reduced amount of NAD that is available, we will see Mallory bodies which are just polymerize keratin. 09:34 Cells may eventually die. 09:36 So we may see hepatocellular necrosis certainly we will see apoptosis. 09:40 And then as a result of that activity, will turn on stellate cells which are going to be our precursor cells normally charged with repopulating the liver, they're going to turn on. 09:51 Not only they're going to try to make new hepatocytes but they're also going to drive fibrosis or scarring. 09:58 At the end stage or cirrhosis, those stellate cells have been activated and laying down a lot of collagen. 10:04 So there's a perivascular fibrosis. 10:07 And then with continuous injury by drinking constantly or by continuous intermittent bouts of injury, that injury and regeneration leads to the stellate cells to drive hepatocyte regeneration that is limited by all of the scarring. 10:26 The damage that's going on, and particularly the scarring and the fibrosis is irreversible. 10:32 And now we're going to have all the secondary consequences of having an abnormal scar in the liver affecting synthetic function, vascular flow and bile elimination. 10:44 What's been shown here are the histologic appearances of the various stages of alcoholic liver disease. 10:51 On the left hand side is a normal H and E stained slide of liver. 10:56 The pink cells are the hepatocytes in their normal courts. 10:59 The cleared out areas represent the sinusoids where blood would be flowing. 11:04 The cells are not showing lipid accumulation and there's no inflammation. 11:08 The middle image is showing you steatosis. 11:11 The individual hepatocytes are now vacuolated. 11:14 That's literally an accumulation of triglyceride because we're not able to undergo lipolysis and as we accumulate that fat, we get clearing. 11:22 Those hepatocytes are alive, they may not be particularly happy, or completely functional, but they're alive and if we take away the alcohol, all this room will revert. 11:33 The panel on the right hand side is showing steatohepatitis. 11:37 There is more profound steatosis, so there's more fat accumulation and now we're starting to get an infiltration of both macrophages or Kupffer cells and lymphocytes which are going to drive the next stage. 11:50 With ongoing injury, stellate cell activation and the deposition of extracellular matrix, we now progress to cirrhosis. 12:01 This is a lower power view from a biopsy of the liver. 12:05 And the darker pinker material at the ends of the pointers is indicating the fibrosis. 12:11 We will get bridging, scarring, that goes from portal triad to portal triad, from portal triad to central vein and from central vein to central vein. 12:20 And this will criss-cross the liver and completely encircle what's left of the normal hepatocytes, which will be trying to regenerate and try to reestablish a normal liver, but they're encased completely surrounded by scar. 12:36 And grossly, we can appreciate this as an irregular nodular appearance of the liver with areas of intervening fibrosis.

About the Lecture

The lecture Alcoholic Liver Disease: Epidemiology and Pathophysiology by Richard Mitchell, MD, PhD is from the course Disorders of the Hepatobiliary System.

Included Quiz Questions

Which liver condition is NOT reversible?

- Cirrhosis

- Hepatitis

- Steatosis

- Steatohepatitis

What percentage of the US population has alcohol use disorder?

- 18%

- 8%

- 28%

- 50%

- 1%

Which statement about alcoholic liver disease is true?

- Women have increased susceptibility.

- Bulimia increases the risk of alcoholic liver disease.

- Hepatitis C virus does not increase the risk of alcoholic liver disease.

- Diabetes is not a risk factor for alcoholic liver disease.

- A low-fat diet increases the risk of alcoholic liver disease.

What qualifies as heavy alcohol consumption for women?

- > 20 g/day

- > 40 g/day

- > 80 g/day

- > 60 g/day

- > 100 g/day

Which cytochrome is involved in alcohol metabolism due to excess consumption?

- Cytochrome p450 2E1

- Cytochrome p450 2E2

- Cytochrome p450 3D1

- Cytochrome p450 3D2

- Cytochrome p450 5E1

What is the pathophysiology that changes a healthy liver to a liver with steatosis?

- Lipid accumulation

- Inflammation

- Fibrosis

- Metaplasia

- Cirrhosis

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |